0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

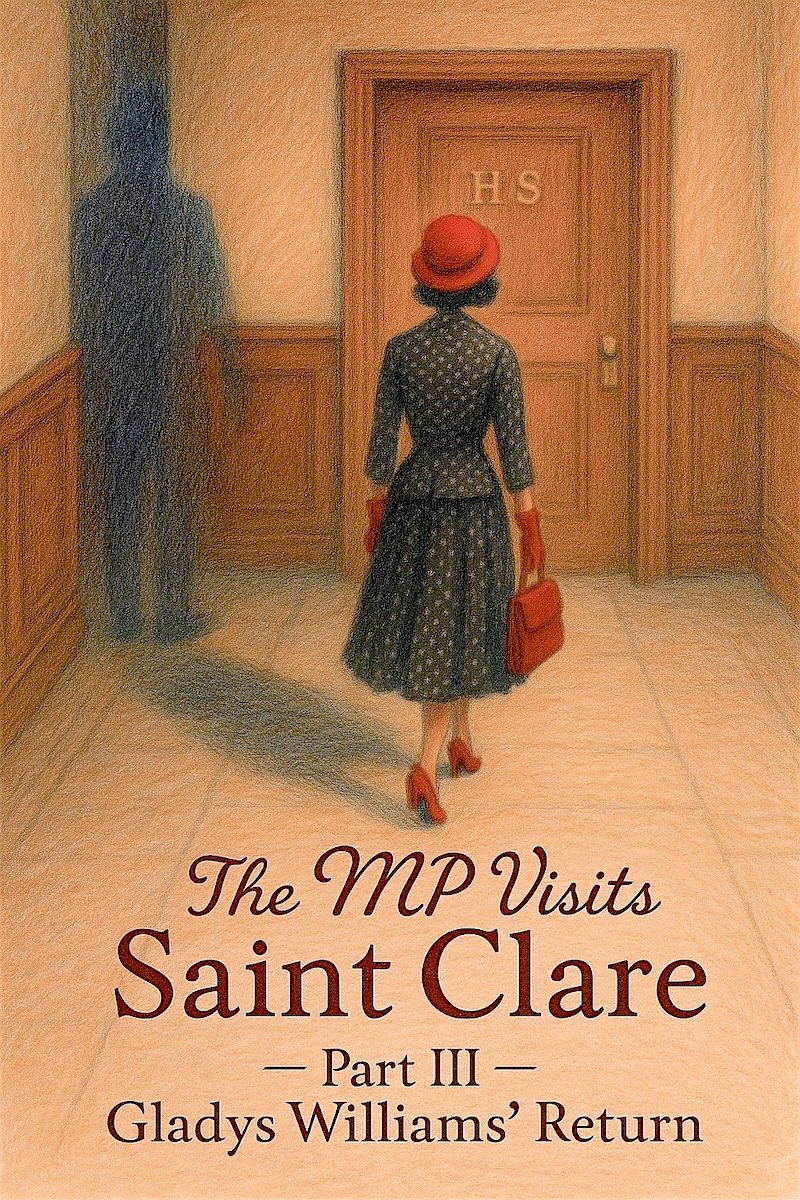

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues

Earlier instalments:

Further particulars may be found in the Foreword.

This sequence draws from the Charrington Papers and the less officious corners of Saint Clare’s—those neat staff reports never meant to withstand scrutiny; the household logs written with a pointed, domestic hauteur; and the diaries, margins, and illicit notes in which the girls record rather more than their elders imagine. Some documents are respectably typed. Others arrive in the swift, unsteady cursive of someone writing under pressure, or in a place she very much oughtn’t be.

Readers are invited to take up the archivist’s task, and the investigator’s pleasure, of weighing the School’s polished accounts against the smudged, contradictory recollections of those who actually lived the day. Much will be implied. Little will be stated outright. And attentive readers may notice that Miss Gladys Williams’s file, though she left Saint Clare more than five years ago, has begun to grow again—curiously, and on no official authority whatsoever.

The archive remembers. And so, of course, does Inez.

Comments are warmly welcomed. While I enjoy seeing them on Bluesky and Twitter, those left here become part of the archive proper, where they may—quietly—shape what follows.

Foreword (From the Archivist):

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

Few who have passed through those doors, whether with contraband in their pockets or mud on their gym-slips, ever forget the sensation. The smell of polish, the sense of one’s sins rising from the floorboards like mist, the dreadful awareness that one’s shoes are suddenly either too loud or too squeaky but never, alas, normal.

Gladys records here the brief march between the playing fields and that fateful door, her glossy heels clicking out a rhythm that suggests not so much “dignified adult woman” as “junior in a very great deal of trouble indeed.” It is one of the more revealing passages in the Charrington Papers: a moment when a grown woman discovers, to her horror, that the past can still catch her by the collar.

This instalment brings us only as far as the threshold. Beyond it, another witness. One who’s far calmer, far drier, and with far fewer personal grievances, will take up the tale.

From Gladys Williams Diary

12 July 1955 continued

Yet there was no way for me to join the Saint Clare girls on the upper fields. Turning away from the bright, joyful noise, I faced the administrative building, every brick of it as unforgiving as I remembered

Here we stepped out of the light and into the dim hallway. That smell! Lavender wax polish, some sort of industrial cleaner, and somehow, beneath it all, a faint whiff of boiled cabbage.

The heat of the motor had wilted me utterly. My suit, the darling black one with the tiny white polka-dots (quite of the moment!) .hung heavy and creased from the long ride, the fitted waist damp where I had leaned against the sticky leather. My little red hat, once crisp, now felt mashed and crooked against my hair, and my matching gloves clung unpleasantly to my fingers. Even my handbag seemed accusatory, its bright scarlet too bold in the dim corridor. Worst of all were the heels, high, glossy, and entirely unsuitable for school tiles. Theye struck the floor sharply with every step, announcing my approach like a metronome of doom.

I would have lingered, looked for the familiar portraits and photos that line the walls, tried to find my class, see if my own face was there, but Gerald walked briskly, clearly with no intention of pausing, of letting my mind absorb this Proustian return, or even have a chance to refresh myself, reapply my lipstick, and run a comb through my hair. After a day spent in the rear of the hot car driving across half the country, I did not look or feel my best.

My heart sank with every echo of our steps. We were not expected, but Gerald carried on as if the place had been waiting for him. Straight down the corridor he went, papers tucked under his arm, walking right past Anne Kelley, formerly two classes ahead of me, now, according to Clarissa, the school’s English mistress. He barely broke stride; in another breath we were at the Head’s study door. Here he paused to rap on it for the briefest of moments before opening it and gesturing me in. He followed close on my heels.

Had he spent the drive planning how this encounter would go? I could hardly move for dread. Only my suspicion that, were I to stop, Gerald would be happy to take me by the arm and march me to stand before the Headmaster’s desk. My pride couldn’t bear that.

Mr Lewis blinked at us from behind his spectacles, surprised to see a party from London arrive unannounced. Gerald merely inclined his head and said:

“A word, if you please.”

The Headmaster invited us in and, sticking his head out the door and, rather absurdly, ordered a tray of tea and sandwiches. As though we were expected and invited guests rather than unannounced gate crashers.

Then Mr Lewis made polite small talk in the way of men who would rather speak on the weather than the subject in hand: the heat of the day, the gardens, the fete that was past. His small talk sounded thin and nervous to me. Mr Charrington answered in kind, dry but courteous. The silences between them lengthened, each one heavier than the last.

And then Gerald, in that dreadful low voice that weighs more than shouting ever could, said what I knew was coming. “Miss Williams,” he said, quiet and clipped, “I wish you would tell the Head exactly what you have done.”

There was nowhere to look. I spluttered, I stammered, I fumbled for an excuse, but he would have none of it. Finally I had to admit it, the envelope slipped along, the letter to Lady de Vries. I told it in little ridiculous pieces, and every bit felt worse once the Head had heard it. The words slid out like stones, and the room felt very small.

The Head took it, and said, polite but firm, that the School could not condone letters carried privately. Mr Charrington responded that he wished the matter on record – and then he asked that ‘his daughter’ be called so he could speak with her privately. My stomach turned. I knew far too well what “privately” meant. I wished, absurdly, that I could flee back into the corridor and become a girl again, small enough to hide behind someone else’s skirts.

Afterword (From the Archivist)

Miss Williams leaves us at the very moment the true drama begins, which is perhaps the most understandable editorial choice she ever makes. No sensible woman, finding herself before the Head’s walnut-panelled judgement chamber, pauses to take notes.

Fortunately for posterity, someone else did – and did so most attentively.

The next document offers an account written by a staff member who, by virtue of long habit and a desk placed at a most advantageous angle, possessed an enviable ear for detail, and used it to excellent effect. Readers should brace themselves: the tone grows no less polite, but the events grow markedly more energetic, as it’s learned, once again, that red is Saint Clare’s colour.