0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

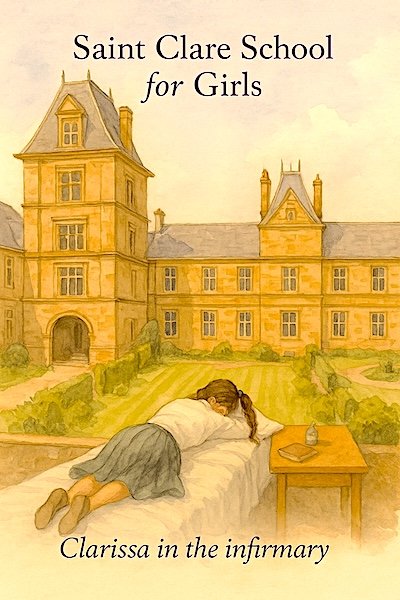

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues

Earlier instalments:

- Prologue – 11 July 1955

- Part I – 8 – 12 July 1955

- Part II – 12 July 1955 (earlier)

- Part III – 12 July 1955

- Part IV – 12 July 1955

Further particulars may be found in the Foreword below.

This sequence draws from the Charrington Papers and the less officious corners of Saint Clare’s—those neat staff reports never meant to withstand scrutiny; the household logs written with a pointed, domestic hauteur; and the diaries, margins, and illicit notes in which the girls record rather more than their elders imagine. Some documents are respectably typed. Others arrive in the swift, unsteady cursive of someone writing under pressure, or in a place she very much oughtn’t be.

Readers are invited to take up the archivist’s task, and the investigator’s pleasure, of weighing the School’s polished accounts against the smudged, contradictory recollections of those who actually lived the day. Much will be implied. Little will be stated outright. And attentive readers may notice that Miss Gladys Williams’s file, though she left Saint Clare more than five years ago, has begun to grow again—curiously, and on no official authority whatsoever.

The archive remembers. And so, of course, does Inez.

Comments are warmly welcomed. While I enjoy seeing them on Bluesky and Twitter, those left here become part of the archive proper, where they may—quietly—shape what follows.

Saint Clare November: 42,924 / 50,000 words

Foreword

From the Archivist

Having concluded Miss Kelley’s contribution to the Charrington Papers—written, as ever, from a strategically advantageous desk—we proceed to the next document set, in which Saint Clare’s own medical wing weighs in.

Clarissa Charrington’s transfer to the infirmary on the evening of 12 July was recorded with the calm efficiency peculiar to boarding school matrons, who tend to regard tears as symptoms, disobedience as diagnosis, and cod-liver oil as cure. Matron Whitlock’s notes provide the official version: measured, sensible, and serenely unconcerned with the child’s sense of dignity.

Clarissa’s corresponding diary entry presents something rather different: a young heroine stunned by shock, shame, and a games skirt that suddenly felt two inches too short for public consumption.

Between the two, the reader may triangulate something like truth.

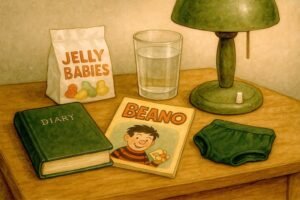

CLARISSA CHARRINGTON – DIARY

Entry 1 – In the Headmaster’s Study

12 July 1955 – Afternoon

It happened. It truly happened. I keep writing the words to make them real, but my hands won’t stop shaking. Papa asked Mr Lewis for the room, and then for me, and he was perfectly calm – horribly calm, the kind of calm that means there is no escape. I thought I knew what it would feel like, being in trouble with Papa, but it is worse when he doesn’t even raise his voice. Worse than shouting. Worse than anything.

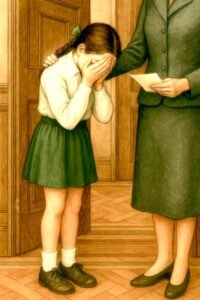

I was marched in still in my games kit, looking a fright. I had grass on my socks and my blouse wasn’t properly tucked in, and all I could think was that if I’d known he was coming, I would at least have changed. But I didn’t know. No one warned me. Georgie Fairfax only said the Head wanted me at once.

Papa stood beside Aunt Gladys, who looked white as chalk and wouldn’t look at me at all. I tried to speak first – I don’t know what I meant to say, only that if I said something quickly, maybe it wouldn’t be so awful – but Papa cut across me:

“Clarissa. Tell me what you have done.”

Just like that. No greeting. No hug. No “my girl.” Only that.

I told him part of it, I think. Or I tried. But I couldn’t make the words come out properly. He asked again – quiet, clipped – and when I still hesitated, he said Aunt Gladys had already told all, and that I ought to be honest. She didn’t look at me then either.

I said I was sorry, that I hadn’t meant to cause trouble, that I had only meant to help. Papa said that wanting something did not excuse breaking rules I knew perfectly well.

And he looked so disappointed in me that I wanted the floor to open.

Then he said THE words. Said them exactly like this:

“Now, over my knee, young lady.”

I thought my knees might give way.

I said no – I did, I said it – “No, Papa, not here, everyone will know, please wait, I’ll be home in less than two weeks – ”

But he interrupted me:

“And what more will you do in those two weeks?”

I couldn’t answer. So I did what he said.

The rest is a blur, except the important parts. The chair scraping. The sound. The way it hurt worse because I knew Miss Kelley was in the next room and might hear everything. I tried to be quiet. I did. But I wasn’t, not in the end.

At first it was only the smacks over my knickers, which stung, but I could bear it. Then he stopped, and for a moment I thought he was finished, but he wasn’t. He only paused long enough to say:

“You know why I must do this.”

And then it was worse – bare, sharp, quick, and Papa’s hand is bigger than any master’s at school. I held on as long as I could, but then I couldn’t anymore, and I cried like a much younger girl. The horrible, shaking kind of crying that you can’t swallow back down. I said I was sorry, I said it over and over.

When it was done, Papa’s voice changed. He held me close and said, “My darling girl,” and that he loved me, and that he wanted to be proud of me. And I cried again because that part hurt too.

Then – just when I thought I could breathe – he said:

“We shall conclude this matter at home.”

I felt everything drop away inside me at once.

We left the study. I could hardly walk. My face burned. My legs shook, and my skirt felt shorter than ever. Miss Kelley didn’t say anything, only put a hand on my shoulder, and somehow that made it worse because it was kind. I didn’t want kindness. I didn’t want anything. I only wanted to disappear.

I kept my eyes on the floor all the way to the infirmary. I was terrified someone would see me, or see the back of my legs, which were as red as my bottom, and I could feel the hem of my skirt swishing too high. If even one girl had looked at me, I think I would have died on the spot.

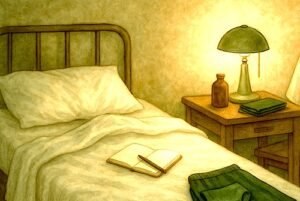

Matron put me in one of the beds and told me to lie on my stomach. She said she would have a look in a moment and that there would be “something cooling,” which only made me dread it more. Then she left me with a glass of water and instructions not to wriggle. I don’t want her to come back. I don’t want anyone to come back. I want to curl up and vanish into the mattress.

I tried to write this lying down, but I couldn’t keep steady, so I propped myself on one elbow and wrote as fast as I could. My hands smell of the wood of the infirmary pencil. My eyes won’t stop stinging. Everything feels too close: the pillow, the blanket, my own skin. There isn’t room for another person in this room, or for another word from anyone.

My friends will wonder why I’m quiet, will want me to say what happened, but I can’t tell them. Not even Inez. She jokes she barely knows what her father looks like, she sees so little of him. How could I tell her this? She would never understand. I don’t feel finished off. Stunned, though. Warned. And I’ll remember. Always.

I don’t know what will happen when Papa comes to fetch me at the end of term. I don’t know what he’ll do. I don’t know if I’ve ruined everything.

I can’t talk to Inez. Not now. Not when all of this is still burning on my skin. I can’t bear the thought of her seeing me like this, or knowing. She’ll think I’m foolish, or careless, or weak. I don’t want her – or anyone – to look at me.

I’m going to stop now. I hear Matron coming. I don’t want to speak to her. Not just her. I don’t want to speak to anyone. I just want her to GO AWAY before I start crying again.

Entry II – Miss Kelley’s Visit

Matron sniffed and said, “None of that, miss. This isn’t your drawing room, and I’m not your maid to be told to send your callers away. May I remind you Miss Kelley is a teacher at this school? She may see you when she wishes, and you’ll certainly see her. You’re not so sore you couldn’t be sorer.”

Then she tucked my blanket down with the sort of snap that means there’s no arguing. I glared at my pillow. At least I don’t have to look at anyone, much.

But I should start over. Before Miss Kelley even arrived, Matron made me take a spoonful of cod liver oil “for shock” and took my temperature the worst way she could. Enough said there.

I argued or tried to, that I wasn’t in shock, only that I didn’t want to talk to anyone, and Matron said, “That is shock, my girl. Imagine thinking you may refuse a teacher, let alone the one who sent you here.” She made me sit up then held the spoon under my nose until I swallowed it. It tasted like bad fish and metal and humiliation all mixed together. I nearly gagged, which she called “perfectly normal,” but also “if you spit it up there will be another dose to make up for it.”

Once she finished I tried to bury my face in the pillow, but that only made my bottom hurt worse, so I had to roll halfway onto my side, which made everything feel stupid and exposed. I could still feel the marks on my thighs every time I shifted. Matron spoke sharply telling me to lie on my stomach, that now is not a good time to disobey her. Or anyone I guess.

At least Matron was done with my temperature and had covered me with the sheet before Miss Kelley arrived. My bottom was throbbing like it had its own heartbeat. I heard Miss Kelley’s shoes before I saw her. She wears the quiet, sensible sort of heels that don’t click loudly like Gladys’ but still enough to let you know a mistress is coming.

Matron said, “I’ll be at my desk.”

I didn’t look at Miss Kelley at first. She didn’t say anything. My face felt hot, and my eyes were burning and watering again, and I knew if she said anything kind I would cry all over the place. She didn’t hover or sit right away. She just stood beside the bed for a moment and then said:

“Miss Charrington… may I come a bit closer?”

Her voice was gentle but not pitying, which made it somehow possible to nod.

She sat down in the chair beside the bed, reached out and brushed some hair off my forehead, and then folded her hands. She said she had seen me brought in. I wished she hadn’t. I wished no one had. I wished Georgie hadn’t galloped across the fields to fetch me in the first place. OR that she’d at least let me change. Would that have been so hard? It would have been like five minutes. She had to know. I wish… I wish everything hadn’t happened.

“I won’t ask you to talk about it,” she said, “unless you want to.”

I shook my head so fast my braid tickled my neck. She nodded like she had expected exactly that.

But just to be clear, I said “No, but thank you, Miss.” Because I do like Miss Kelley. She’s my favorite teacher. Though I’m sure I’m not her favorite student, if I ever had a chance.

Then she said something that made me want to cry again for a different reason:

“You were very brave.”

I choked. Brave? Me? Crying and kicking like a child over Papa’s knee? Begging him to stop.

She must have seen my face because she gave the tiniest smile – the sort that makes one line at the corner of her mouth. If she weren’t so kind it would be a smirk.

“Bravery isn’t always quiet. Sometimes it’s simply bearing what must be borne. And you did. It’s over now.”

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t trust my voice. I stared at the blanket instead. Miss Kelley just waited, the way she does when she’s giving you time to think in class.

My bottom throbbed. My thighs stung when I moved even a little. My games skirt and knickers lay folded over at the end of the bed, and I kept worrying someone might walk in and see it and know exactly why I wasn’t wearing them. Miss Kelley surely knew. My face probably looked as awful as I felt.

After a while, Miss Kelley said softly:

“I expect you’re feeling very small just now.”

My lip wobbled, but I managed to say, “Yes. Like I could break.”

“It will pass,” she said. “Humiliation always feels endless in the moment, but it has a shorter life than you’d think. A few days – perhaps even tomorrow – you will look back and find you’ve survived it. And everyone will forget.”

I didn’t believe her. Not completely. But something about the way she said it -as if she’d lived through worse- made a tiny bit of the panic unclench in my chest. I felt tears trickle out of my eyes and wiped at them with my shirt sleeve.

Miss Kelley gave me her handkerchief. It smelled of linen, and starch, and something sweet. Lemons?

She didn’t ask about Papa. She didn’t ask about the letter. She didn’t mention the Head’s office at all. I think that was her kindness. Instead she said:

“You have two weeks left of this term, your first term. They can still be good weeks, if you let them.”

I almost said, “it’s not over. Papa said he’ll finish it at home,” but the words jammed in my throat. I didn’t want them to exist outside my own head. In my head I could hear and feel the hairbrush thwacking my bottom as I went over his knee again. I squeezed my eyes shut. Miss Kelley didn’t need to hear about that.

She reached out – very slowly – and smoothed a bit of my hair where it had worked loose from its braid. The lightest touch, but it nearly undid me all over again.

“When you’re ready,” she said, “you may find your friends are ready too.”

I shook my head. Hard.

She didn’t argue. She just stood, smoothed her skirt, and said she would tell Matron I needed to rest. She walked away from my bed. And then, nearly at the door of Matron’s office:

“One last thing, Clarissa. You are not alone. Even when it feels like you are.”

She left before I could say anything back.

Didn’t she understand? I want to be alone. This hurts so much inside I feel like I’ll fly apart if I have to tell anyone. Anyone at all. Alone I can be very still. Very quiet.

I stared at the door for a long time after she went. My throat was tight and hot again, but not in the same awful way as before. I still don’t want to talk to anyone. Not yet. But it doesn’t feel quite so impossible. I can almost imagine doing it some day.

My bottom still hurts like fury. My legs sting if I shift even a tiny bit. But my chest hurts a little less.

Maybe I can sleep now.

I hope Matron doesn’t come back with more cod liver oil. She probably thinks it helps with sleep. She has been in twice since Miss Kelley left. Twice. I don’t know how someone can creak so loudly and still walk so softly at the same time. She says she is “checking on me,” which really means she is checking whether I’ve moved — which I haven’t, except when I absolutely had to because everything aches.

She took my temperature again. AGAIN.

The light is dimmer now – that awful yellow infirmary lamp that makes everything look sallow – and the blanket feels scratchier the longer I lie on it. My skirt and knickers are still folded at the foot of the bed, and every time I see them, I feel the heat rush back into my face. I keep imagining someone walking in and noticing and knowing exactly why it’s there and not on me.

Matron came in the first time with a little tray of bottles and things and said, “Right, miss, let’s have a look.” I wanted to melt straight into the mattress. I asked if she could just leave me be, and she said, “Not when you’re in my care, I can’t.”

I turned toward the wall as she lifted the sheet while she made that humming noise Inez said she does when she’s taking stock.

“Still very red. I can feel the warmth and even the welts from your father’s fingers. You’ll likely have some bruises in the morning, I fear.”

Oh my GOD! I wanted to crawl under the bed. I said, ‘Matron, don’t say things like that,’ but she only sniffed and said”

“I must say them, my girl. Those marks won’t fade on good intentions. Unless you mean to keep them as souvenirs to show your classmates, you will let me look after them.”

She dabbed something cool on the worst spots. It stung at first and then went almost numb, which was a relief — though I’d never tell her that. She told me to hold still because wriggling “only makes it last longer.” I don’t know if she meant the salve or the whole evening. She rubbed in some sort of cream in circles. It would have felt good if I weren’t so embarrassed.

When she finished, she helped me into my nightshirt and said I was to lie exactly as I was for fifteen minutes, then drink the glass of water she put by the bed, then rest again. I said I wasn’t thirsty.

She said, “Did I ask you a question? Bottoms bruise less and heal faster when the rest of you is hydrated,” which sounded like utter rubbish but also like something she might have statistics for, so I drank half of it just in case.

She adjusted the curtain around my bed as if I were contagious. I suppose in some ways I am: contaminated by disgrace, by the kind of humiliation that clings. She didn’t cover my bottom back up, but left me bare, my nightshirt still pulled up, sheet down below my knees. I could have pulled it up, but didn’t. The cream made the air feel almost cool.

When she left, I listened to the click of her shoes fade down the hall and then stop entirely. I thought she might be speaking to someone. I imagined Georgie Fairfax. Or Ronnie Or even Sally, the head girl, whispering about me. I imagined someone asking, “How bad?” and Matron saying, “Bad enough.”

Would she though? Maybe for a teacher. Not another girl.

It made my stomach twist so tightly I had to put the diary down for a minute.

Matron returned again later, just to check the salve, she said. She asked if I’d rather sit up for a bit. I said no so fast she actually blinked at me.

Then she said calmly, “Good. You won’t want to put weight on that for a while.” And she gave me a look — not unkind, but not indulgent either — the look of someone who has seen a thousand girls cry for the same reason and knows precisely how this goes. She pulled my nightshirt down and the sheet up.

She asked if I wanted cocoa. I said no. She asked if I wanted a hot water bottle. Also no. She asked if she should fetch Miss Kelley again. I looked at her like she was insane. Absolutely not. Then she made a very small sigh and said, “You’ll feel better for talking to someone when the moment’s right.”

I won’t.

Not yet anyway.

Not about this. She waited another minute then said I might as well go to sleep. I think I did. For a little bit anyway.

The corridor is quiet now. I think it’s past lights-out. I can hear the faintest giggling far off on the landing — the sort girls do when they’re trying to be quiet. Loudly quiet Inez says. Thinking that makes my chest hurt a little, because a few hours ago I was part of that world, and now I feel like I’ve been scooped out of it and left behind somewhere else. I’ll never be able to fit in, no matter how many Jelly Babies I have to share.

Which makes me think about what Papa said:

“We shall conclude this matter at home.”

NO!! I feel sick if I think about it too long.

My thighs still sting.

My thighs still sting.

My bottom aches.

My chest feels scraped raw.

I don’t know how to sleep like this.

I don’t know how to face everyone, or anyone tomorrow.

I don’t want more visitors.

I don’t want Matron’s cocoa or her fussing. (well, maybe that cream again. But no talking.)

I don’t want Georgie Fairfax peering in.

And I don’t want—

Inez.

My friend.

Not yet.

Not when everything still feels like it’s burning.

Still, I confess, part of me is listening for footsteps in the corridor.

I don’t know why.

Entry IV: Inez’s Visit (Long Past Lights-Out, close to the summer dawn)

(handwritten — uneven pressure, some smudged bits)

I was finally drifting off. The hurting had settled into something dull and throbby, and Matron had stopped doing her creaking patrol. That was when I heard the tiniest tap at the curtain. Not a Matron tap. Too light. Too quick. Too polite. How do you tap a curtain anyway. It was so quiet I could hear someone not me breathing.

I froze. I thought it might be Georgie, or Ronnie, or someone come to gawk and gossip.

I froze. I thought it might be Georgie, or Ronnie, or someone come to gawk and gossip.

Then a whisper:

“Clary? Clary? Wake up.”

Only one person calls me that.

I whispered “Go away” — or, at least, I tried to, but it came out wobbly and stupid. It cracked in the middle with a little sob even though I hadn’t cried for hours. Will she think I was crying the whole time?

The curtain pushed back, just a few inches, and Inez slipped through like smoke.

She didn’t look nervous at all, though she must have dodged three prefects and walked through the Sixth forms rooms to get here. Inez wore her dressing gown over her nightdress, its missing belt replaced with her red gymslip sash tied in a crooked knot, as if she’d raced all the way from Upper IV.

“I thought Matron would be with you,” Inez whispered.

“She was,” I said. “She’s gone now. Everyone is gone.”

“No,” she said. “I’m here.”

I looked up. Inez tilted her head the way she does when she’s evaluating something. Judgement. It made me want to disappear under the sheet. I pulled it up higher without thinking, and that made my bottom twinge, which made me wince, which she definitely noticed.

She came and sat on the edge of the bed — very lightly, so it didn’t shift. Trust Inez to know exactly how to sit on a sickbed without jostling.

“I heard what happened,” she said quietly.

I wished the bed could swallow me. And then floor would swallow the bed. And I’d be gone.

“Everyone must know.”

“Not everyone,” she said. “Most of them are useless at keeping track of anything not directly in front of their noses.” Then, seeing my face, she added, more gently: “But yes. Enough know. Everyone will by tomorrow.”

I couldn’t look at her. I stared at the pillow instead.

Inez stroked my hair, her fingers so gentle, so barely there I shivered.

“I’m sorry,” she said after a moment.

That shocked me enough to look up. Inez de Vries apologising is like Mr Green singing in a musical — it simply does not happen.

“You shouldn’t be,” I whispered. “It’s not your fault.”

She didn’t answer right away. “No,” she said at last. “But yes too. I helped set the match to it. You were helping me. And you’re the one who’s paid most”

I didn’t know what to say. There didn’t seem a right thing.

“You got caned. It was just a spanking. Papa, he, he only used his hand.” I hope I sounded brave.

She looked at me properly then — not staring, not pitying, just looking. “Tell the truth. Was it very bad?”

I couldn’t speak. My throat locked up. I hate that. Inez waited. She is maddeningly good at waiting.

I finally looked up at her and nodded.

She nodded back. She’d already known.

“And Papa—” I started, then stopped. The words felt too big. “It’s not fair, but Papa…”

Inez finished it for me. “I heard he said he’d finish it at home.”

I nodded before I shut my eyes. She must have heard Miss Kelley tell Matron or Matron tell someone else or Georgie overhear something. Saint Clare secrets last about six minutes. If you’re lucky.

I said, “My mum died, but he has her hairbrush. Her “head girl” hair brush. It’s the worst. I don’t know how I’m supposed to get through the rest of term.”

Inez rested her hand on top of mine. Very briefly, very lightly, as if she’d practised not frightening animals.

“You will,” she said. “You’re stronger than you feel right now.”

I shook my head. “You don’t understand.”

She didn’t deny it. Her mum was a head girl, but my life is not like hers.

“No,” she said softly. “My father’s never done anything like that. I don’t think he’s ever spanked me. If he had, I’d remember. He’s aways a lot. I barely recognise him at Christmas. But…” She paused. “…but my mum has the head girl brush too, somewhere. WE all survive it, in a way.”

I laughed then — a tiny awful laugh — because somehow that was both the stupidest and truest comfort I could ever have been given.

She didn’t smile, but her eyes went warmer. “Besides,” she added, “your Papa CARES. He won’t hurt you. MP Charrington won’t do anything you can’t bear. Though maybe that’s almost worse, I know.”

I nodded. Hard. Too hard. It hurt.

Inez glanced toward the doorway. “I can’t stay. But I wanted you to know you’re not alone.” I thought of Jane curled up with Helen and wanted to ask her to sleep with me, just for a few hours. “Don’t go,” I choked, now starting to cry despite not wanting to. I felt my face screw up.

Inez said quickly, “Don’t cry, you’ll bring Matron—”

“I’m not crying,” I said, which was an enormous lie.

“…and her cod liver oil.”

So my sob turned into a choked laugh.

“I’ve already had my dose. Twice. And her thermometer.”

She stood, light on her feet as always, and tucked the sheet up near my shoulder, almost exactly as Miss Kelley had done earlier, but different. Faster. Less motherly. More like a promise.

“Tell me tomorrow if you need anything,” she whispered.

I said, “I don’t know what I need.”

She nodded once. “I have to go. But I’ll come get you so we can go into the class together. Wait for me here.”

I nodded, not trusting my voice.

As she slipped back through the curtain, she looked over her shoulder and said, “Good night Clary.”

“My Papa calls me ‘Rissa.’”

“And I call you Clary.”

Then she was gone.

Silent as a cat.

I cried a little after she left, but very quietly, and not the awful kind of crying from before. More like something letting out.

I’m tired now. My legs still sting. My bottom aches. But my chest hurts less than it did.

I don’t want to be seen tomorrow.

But Inez will be there. Maybe I can bear it.

A little.

Maybe.

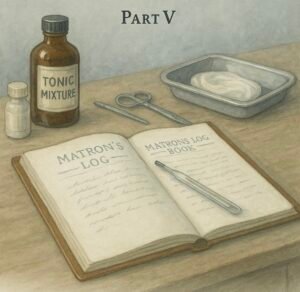

Matron’s Infirmary Notes:

File: Extracted from the Archives of Saint Clare’s School for Girls

Document: Notations from Matron’s Logbook, 12 July 1955

Student:

Charrington, Clarissa (Upper IV) sent to the infirmary by Miss A Kelley.

12 July – 4:10 p.m.

Miss Charrington ran into the infirmary in visible distress, wearing games uniform, tearful, dizzy and with difficulty walking with proper steadiness. Not clear for several minutes whether distress is emotional or physical. Clearly overwhelmed.

Observation: Blouse and games skirt disordered; knees grass-stained; ribbon slipping.

State consistent with having been called indoors directly from the playing field. Simple examination showed the reason was corporal punishment – redness observed on her upper thighs.

Eyes red. Face blotchy. Refused to look up until spoken to sharply.

Directed her to remove her games skirt and knickers and lie on her stomach. Initially refused. When I returned with the salve and a cool flannel she was laying on the bed, on her side, face to the wall, still fully dressed. Reminded her she’d already been punished once today, that she didn’t want to find herself across my lap too.

At that, Charrington complied slowly, embarrassed now that she was required to undress in front of me.

Charrington placed in Bed 3. Directed to lie on stomach. Finally complied.

Emotional state: embarrassed, resistant to speaking, generally overwrought.

(Nothing unusual in girls of that age following disciplinary interview.)

4:20 p.m.

Assessment: Charrington’s buttocks, and upper thighs markedly reddened. Finger. marks visible halfway down her thighs. Skin surface warm to the touch with heat still rising at surface.

She flinched and attempted to hide face in pillow and initially demanded, then begged to be left alone. Declined to answer questions beyond “I’m fine” and “please don’t.” (Tone not convincing.)

Applied cool witch-hazel compress. Child hissed involuntarily.

Reassured her that this was expected.

4:45 p.m.

I asked her questions about her punishment to assess mental state. Charrington refused to speak.

Informed her that silence is not a medical plan but she continued silent.

After my third question was ignored, I had her sit up and administered 1 teaspoon cod-liver oil “for shock.” Directed her to lie back down and took her temperature. Slightly elevated.

Justified: trembling hands, pallor, rigid posture, and—most telling—insistence that she “doesn’t need to see anyone this evening,” which is diagnostic in this infirmary.)

Charrington’s reactions: grimaced, swallowed with difficulty, attempted protest temperature taking but was too late.

Colour improved shortly afterward.

5:20 p.m.

Miss Kelley arrived to check on her pupil, bringing with her a clean nightshirt, fresh uniform, and her diary and pen.

Charrington attempted to refuse visitor. Corrected her firmly reminding her that teachers may see their pupils when they and I deem it appropriate.

Left them for brief conversation. (Volume low; propriety maintained.)

Following her discussion with Charrington, Miss Kelley discussed the afternoon’s events with me, explaining this was parental rather than school discipline. She had received a hand spanking from her father in the Headmaster’s Office in front of aunt (Gladys Williams). Inez deVries’s involvement clear but she was not in attendance.

No school witnesses, but was overheard by Miss Kelley who judged it a hard spanking though with his hand rather than implement. Door left ajar, which seems careless were the punishment intended to be private. On seeing Charrington after, Miss Kelley directed her to the infirmary which seemed appropriate. I agree Charrington should have a quiet evening.

7:05 p.m.

Re-examination showed Charrington is calmer, eyes less swollen though still tear-prone.

Pulse steady. No fever. Helped her change into a night shirt only, no knickers. A cool flannel cleaned her up a bit.

Issued the following instructions for this evening:

• remain on stomach at least one hour;

• no running about;

• stay overnight in the infirmary; no joining the Upper 4th in the Common Room until following morning;

• report any renewed soreness.

Supper: half-slice of bread, butter, weak tea.

Child ate reluctantly. (Likely embarrassment more than appetite.)

Lights-out: permitted pencil and paper “for quiet reflection” to settle nerves.

(Child promised to stop writing if her tears returned. She did not keep this promise, however her crying remained mostly controlled )

13 July — 6:30 a.m.

Charrington reported stiffness but no acute pain.

Skin shows expected tenderness; colour fading to blotchy pink. Re-applied salve and cool compress after morning wash.

Emotional state: subdued, ashamed, avoids eye contact, speaks only reluctantly.

Also refused porridge. Ate toast under supervision after being asked if she required another dose of cod liver oil.

I informed her she was well enough to attend her morning lessons; she cried quietly when my back was turned (though briefly and controlled).

Walk slightly guarded but functional. Eyes are downcast.

Permitted her to dress in full uniform, including knickers, though the elastic is likely painful. Brushed her hair and checked appearance. Miss Kelley arrived with Inez DeVries following.

Released Charrington to Miss Kelley for morning lessons with note to her teachers that she be permitted to stand during lessons if needed.

General Remarks

Charrington appears conscientious but excessively anxious about peers’ opinions. Should be watched closely in case of any bullying by other girls.

Shame more lasting than discomfort. Strong startle response whenever someone enters infirmary; suggests episode felt “public” to her, though door to study was (part way closed.

Recommendations: discreet observation for remainder of week, no further disciplinary measures from staff until child is settled.

(If any are required, inform infirmary beforehand; her thighs are still tender.)

Matron P Rowntree

Afterword

From the Archivist

Thus concludes the curious case of 12 July 1955 — a day that began with damp gloves in a Wolseley, worsened with a Headmaster caught between tea-tray diplomacy and Charrington determination, and ended with a girl in the infirmary writing furiously against her pillow.

Viewed in sequence, the events form a tidy moral diagram straight out of the Saint Clare School tradition:

• Part I: A weekend at Birchwood House in which tempers are frayed, the milkman vanished, and Gladys’s patience with domesticity proved shorter than her skirt hem.

• Part II: The journey to Wales, where the hamper was deemed a personal attack and Fowler bore silent witness.

• Part III: Gladys’s grand return to the Headmaster’s study, accompanied by the full force of her hat, gloves, and indignation.

• Part IV: Miss Kelley’s discreetly overheard account—scholarly, mortified, and, through no fault of her own, extremely well-positioned.

• Part V: Clarissa’s retreat to the infirmary, where Matron applied witch hazel, cod-liver oil, and the sort of practical wisdom that has withstood generations of tears.

From the hamper to the Headmaster’s door to the infirmary curtain, each witness offers her own perfectly partial truth. Set side by side, the accounts reveal the pattern common to most Saint Clare crises:

The adults were flustered, the girls were mortified, and the archives—inevitably—prospered.