11 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

The story of Inez de Vries’s experiences in the summer of 1955 unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained.

The story of Inez de Vries’s experiences in the summer of 1955 unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained.

But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

This story goes back to 1938 and tells the story of Inez’s parents, especially Lady Gwendolyn “Honour” deVries, a St. Clare Old Girl who notices far more than most people realize.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here and promise to respond. Moreover your responses and ideas are included in the archives and may shift and change the story’s evolution.

Having trouble with the handwriting? Try the plain text version.

This story follows:

You might want to read them first.

From The Archivist:

From the Lady de Vries Collection, Blue Room Archives, Saint Clare’s School for Girls

The papers presented here form part of what is now known as the Lady de Vries Collection. Though the correspondence was originally preserved among the private files of her husband, Edmund Alexander de Vries, 9th Earl of Darlington, its preservation and eventual deposit at Saint Clare’s are due to Lady Gwendolyn Randolph de Vries herself.

The exchange of initials — D. and H. — occurs throughout. Their precise origins are unclear; however, internal evidence suggests that these letters were both a private correspondence between husband and wife and, increasingly, a record of informal “exercises” undertaken by Lady de Vries during the late 1930s.

The editors have retained the original orthography and punctuation. A few later pencil notes in Lord Darlington’s hand are reproduced in grey type. Where the line between affection and assignment blurs, readers are invited to remember that the world beyond these pages was also shifting — toward war, secrecy, and a very different kind of education.

Introduction

Introduction

The archive continues.

In these documents, the young Lady Honour de Vries begins to master her husband’s “exercises”—tasks meant to discipline her curiosity and temper her impulsiveness. Yet what began as a private game of observation now reaches beyond the drawing room. A tea in Chester Square leads to the American Embassy at Grosvenor Square, and the world of polite conversation begins to tremble with rumours of the coming war.

Through reports, annotations, and private diaries, we see the gradual shaping of a partnership: his precision against her wit, his restraint against her appetite for understanding. Honour still writes to please him—but she is also beginning to see, to listen, and to turn the rules of his game to her own advantage.

The tone remains domestic, almost playful. Yet under its surface, something colder and more intricate begins to form.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I enjoy seeing them on Twitter and Bluesky, I especially love receiving them here and promise to respond. Your observations and ideas are entered into the Saint Clare archives and may subtly shift the story’s evolution.

Having trouble with the handwriting? Try the plain-text version below.

Part Two

From: The Blue Room Collection, Saint Clare’s School for Girls

Recovered documents: November–December 1938

Exercise — 20 November 1938

You are to attend Mrs. Allerton’s tea tomorrow afternoon. Treat it as a continuation of your previous exercise.

Instructions:

-

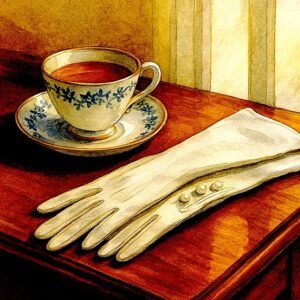

- Keep your gloves on at all times.

- Decline the cakes; they are dreadful, and you think better on an empty stomach.

- Smile when spoken to, but answer only when asked. Listen for what is not said. Women talk freely when they believe you bored.

- Write it afterwards, while the voices are still fresh.

- Keep the tone measured, not arch.

- Distinguish what you know from what you think you know.

Deliver your report to Darlington on the same evening. Late papers will be penalised.

You do not want to be a naughty girl, my Honour.

Honour’s Report: The Allerton Tea

20 November 1938

To: Darlington

From: Honour

Occasion: Tea at Mrs. Allerton’s, Chester Square. Weather bright but sharp; the drawing-room draughty even with the fire lit. A silver tray of stale biscuits circulated, and the tea was thin. Champagne offered “for warmth,” though no one drank more than a half glass.

Method: Sat quietly on the small sofa nearest the window, where I could see the street but seemed out of the main conversation. Kept my gloves on, as directed. Smiled when spoken to, but answered only when asked. Declined cake (I noticed you were right about them).

Observations:

– Mrs. Allerton told, at length, the story of her Pekinese dog’s new diet. (Can add significantly more detail if required.)

– Miss Fairchild announced she is off to Switzerland “for her health” and will stay at a sanatorium in Davos. Everyone nodded, no one asked why.

– Mr. Birtle from the Ministry made a joke about “broken glass” and “our little outpost in Vienna still clinging on” When no one laughed, he changed the subject to hunting.

– A parcel arrived mid-tea — brown paper, twice tied with string, addressed to Mrs. Allerton but signed for by Mr. Birtle. She ordered it be sent upstairs and placed unopened on her writing desk.

– Miss Fairchild coughed often and rather theatrically, but her hands did not tremble when she poured.

– Mrs. Allerton rang twice for the maid, who pretended not to hear.

Assessment:

The talk was mostly dull. Still, the parcel seemed odd, and Mr. Birtle’s joke odder. I wrote them down as best I could. I suppose it is not my place to decide what is trivial and what is not.

Postscript:

I find I rather like these exercises. They make even dull people interesting, once I begin to listen for what they hide. But I still think you could send me somewhere with better biscuits.

Your,

Honour

Ned’s Margin Notes, in pencil

Good attention to detail. The tone is steadier; less embroidery.

Mrs. Allerton’s dog: irrelevant, but the phrasing amused me. Keep such diversions short.

Miss Fairchild’s “health”: plausible cover, but Switzerland often means more than sanatoria. Watch who corresponds with her.

Birtle’s “broken glass” and “outpost in Vienna” — careless and questionable language. Worth remembering.

Parcel: interesting. Why was it signed for by him and not her? Why the insistence on her desk, unopened? Record any future references to letters or packages.

“Miss Fairchild coughed often and rather theatrically, but her hands did not tremble when she poured.”

Who noticed? How did they react? These silences matter as much as speech.

Do not laugh often. Consider feigning not understanding — you would do well to be underestimated, as then you will either vanish or be explained to.

Good, Honour. You are learning to listen. Be careful, though — curiosity can make as much noise as carelessness.

You improve. But that’s enough praise. If I am not cautious, you will grow insufferable.

Exercise – Embassy Ball

Wednesday, 14 December 1938

You will accompany Darlington to the reception at the American Embassy this evening, dressing your part as the young Lady de Vries.

Treat it as observation under supervision. The company will be louder, the lights brighter, and discretion rarer.

Instructions:

– Attend to what people repeat; repetition is the refuge of the uncertain.

– Note who speaks of “Europe” and who of “peace.” The distinction is useful.

– Accept drinks only from me. I will attend to the level of your glass.

– You may dance once. Choose your partner with care. A man’s choice of conversation is often more revealing than his steps.

– I will dance with you after and then refresh your beverage. Never drink from a glass you have set down.

– Listen for what the Americans ask and what they assume.

– Record afterwards what you recall of faces and phrases; accuracy first, charm second.

– Keep your gloves on. The Ambassador’s wife counts fingerprints as well as introductions.

– We will take our leave by eleven o’clock.

Deliver your report on 15 December before you join me for breakfast at 9:00am. Do not oversleep. If I must wake you, it will not be gently. Recall how unsympathetic I am before coffee.

You do not want to be a naughty girl, Honour.

Honour’s Report: American Embassy Reception

Thursday, 15 December 1938

To: D. From: Honour

Occasion: Reception at the American Embassy, 1 Grosvenor Square. Weather damp and raw; the ballroom overheated and full of optimism. American flags and English laughter everywhere.

Method:

Arrived with Darlington promptly at nine. Remained at his side through the first half-hour, then circulated briefly. Kept gloves on. Accepted no drink not offered by you. Danced once with Captain Maynard (Naval Attaché, U.S.) as permitted. Danced after with you. Departed by eleven. Wrote notes on return while my hair was still pinned and my shoes still tight, as you have instructed that impressions fade with comfort.

Observations:

– The Americans speak loudly and laugh easily. They repeat “peace” often, and always with a capital letter.

– Captain Maynard, tall and sun-browned, described the Munich Agreement as “a patch on a leaky roof.” When I asked how long he thought it might hold, he said, “Until it rains.”

– He seemed delighted to be asked at all. I believe he would have talked the entire evening had I not insisted he dance. His manners are excellent, though his optimism seems learned rather than felt.

– Lady Fenton told anyone who would listen that she finds Americans “refreshingly direct.” They, in turn, appeared to find her alarming.

– Mrs Ashworth spoke again with Mr Birtle near the French doors. He gestured westward with his glass when saying “we must look across the Atlantic,” then immediately turned east to glance at you.

– I met the Ambassador’s wife, Mrs Kennedy — charming, brisk, with that unmistakable Boston accent. She seemed curious about my conversion and spoke kindly of her own church in London. She knew more of the de Vries family than I expected; apparently your great-grandfather’s Catholic loyalty during the Reformation is still a matter of diplomatic gossip. I found her conversation more candid than most of the men’s speeches.

– The Ambassador himself spoke earnestly of “Mr Chamberlain’s good sense.” I smiled and said nothing.

– You danced impeccably. (That remains an observation, not embroidery.)

Assessment:

There is much talk of goodwill and little of consequence. The tone is not confidence but exhaustion disguised as gaiety. Captain Maynard seems less naïve than his superiors; Mrs Kennedy rather more perceptive than most of the men.

I remain uncertain whether these people are more dangerous when they talk or when they stop.

Postscript:

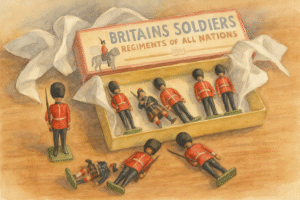

I have delivered my report before your breakfast, though I confess I am only barely awake myself. I will expect my coffee — and my marks — presently. I have also already sent a note of thanks, together with a small box of British toy soldiers for young Edward (Kennedy), who is attending Gibbs in London. Mrs Kennedy remarked that her own boys are devoted to their playthings, and I told her my own Edward had loved his when he was small. It seemed a polite and fitting token — and perhaps a reminder that the world still trains its armies early.

Yours,

Honour

Ned’s Margin Notes, in pencil

The report’s structure much improved. Observation sharper, tone measured.

– Maynard’s metaphor well captured; worth keeping. You chose your partner shrewdly. Officers talk most freely when they believe themselves charming the room.

– Lady Fenton’s conversational enthusiasm: tedious but accurately rendered.

– Birtle again. His gestures betray more than his words — note pattern of repetition at each function.

– Mrs Kennedy is a: perceptive woman. Take care; she observes more than she reveals. I suspect she found you interesting.

– The Ambassador’s “good sense”: record the phrase exactly. It will date poorly.

– Your closing remark on “goodwill and exhaustion” — apt. Retain it.

The postscript amused me. The gift appropriate, if perhaps too British. The Kennedys, with their Irish sympathies, are unlikely to have given young Edward a regiment of redcoats. Still, the thought was charming, and your account of my own toy soldiers unexpectedly kind.

Do not, however, make a habit of charming ambassadors’ wives — or of sending toy soldiers to any Edward but me.

Good, Honour. Continue.

Your own,

D.

Honour’s Private Journal

Thursday, 15 December 1938

(Not to be shown. Burn if ever found.)

I feel quite grown-up tonight. The Embassy was nothing like the “bad biscuit” tea — the rooms were bright as a theatre, full of polished laughter and perfume and the rustle of taffeta.

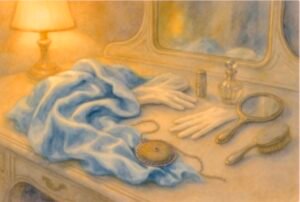

I wore the pale cornflower satin gown — the one Madame Lenoir said was “too young for gravitas, too grown-up for innocence.” I rather like that. The gloves were white kid, long to the elbow, though I had to hide a tiny ink stain on the right thumb where I’d tested my new pen that morning. Ned said nothing, only looked me over once and nodded, which I think meant approval. It felt strange to stand beside him looking so adult.

He gave me an early Christmas gift before we left — a tiny silver réticule from Cartier, so small it barely holds a lipstick, compact, and handkerchief. He showed me how to open its hidden compartment, “for small valuables,” he said, though I saw the glint in his eyes when he added, “or a letter, if one must be carried unseen.” Inside he had already placed a tightly rolled ten-pound note, “for emergencies.” I have no idea what sort of emergency he imagines, but I intend to find out.

I behaved perfectly, I think: gloves on, smile measured, not a crumb nor a drop out of place. And yet, it was rather a triumph to realise how little anyone truly noticed me. They spoke as if I were simply another pretty young wife, pleasantly feather-brained and harmless. It’s astonishing how much people will say when they think one too silly to understand.

Mrs Kennedy was lovely. She has that calm, assured kindness of a woman who knows exactly who she is. When she spoke of her church I felt something like home; she squeezed my hand and said she hoped London was kind to me. I nearly told her it depends which London one means.

The dance was my little experiment. I had decided beforehand to ask nothing, to simply look — and see what happened. I chose Captain Maynard because he seemed the only man in the room who still stood square on his heels. I caught his eye across the floor, smiled, and that was all it took. Within a minute he had found someone to introduce us and was asking if I might spare him a turn. He talked easily, almost too easily, but I realised how much he wanted to be listened to, wanted to explain things to me. He spoke of the sea, of weather, of peace — always peace — and looked relieved to have said it aloud. I listened and nodded and said nothing clever, and yet he told me far more than he intended. It was almost too easy.

Ned looked so proud when we danced. He pretended not to watch me earlier, but I knew he was counting every step. I think he was pleased — he didn’t scold once, only that little half-smile that means well done, but don’t show off about it. I wrote my report straight away, and when I slipped it under his study door before breakfast I felt quite the secret agent. Imagine me — Honour de Vries, recently a St Clare Prefect, a gymslip miss — carrying messages before dawn!

Still, I can’t quite stop smiling. Perhaps I am good at this game — whatever game this is. Perhaps I shall write a little note to Lady Fenton tomorrow. She was horrid at first, but she does talk so freely once she thinks one harmless. If I can make her write as freely, I think it would please Ned no end. And, if I’m honest, it pleases me to please him.

For now I shall sleep a few hours and see whether he brings the coffee himself. I rather hope he does. He said he would not wake me gently, and I find I keep wondering just what that means.Perhaps, sometimes, his Honour does want to be a little naughty.

Darlington’s Private Notes

15 December 1938, midnight

H. performed admirably. As expected, she carries herself as if she has always belonged in such rooms, as she has been educated to do. But now, though, she listens more intently. I watched her speak with Mrs Kennedy and saw that curious spark that passes between women of entirely different kinds who nonetheless recognise one another. Religion is the polite cover for what they share: endurance, discipline, and a taste for invisibly managing men.

Her choice of Maynard was astute. A naval officer, American, young enough to talk freely, old enough to think himself discreet. She handled him well — too well, perhaps. A glance, a smile, and she had him talking of weather, war, and weariness before the band had played its second waltz. She is learning instinctively what others spend years acquiring.

She has good instincts, but I must not encourage her too much. She is my wife and hardly more than a schoolroom miss; yet I find myself wanting to push her — she is unexpected, and therefore could elicit far greater candour than I. She writes, observes, obeys — and all the while learns how to disobey more intelligently.

An exercise in composure and control becomes instruction in the quiet arts of discretion. Do I dare continue down this path? What might be the risks? How much does she already understand?

The phrase she recorded — “goodwill and exhaustion” — is accurate, perhaps more than she knows. The room was full of tired men, congratulating one another on their illusions of peace when all are hearing the hoofbeats of war..

I cannot quite share their comfort, or hers.

Oh, this is magnificent!

Thank you! My only hope is that readers are having half the fun I am.

Dear Mija, I’m enjoying your stories immensely! As you know I stumbled upon your blog recently, and often feel like Donny in Big Lebowski, out of my element.

The link to Honour’s Lesson , close to the top of the page, actually leads to a different story. I knew that there is a spanking hiding in it somewhere, so I persevered, and it was delightful, but you might want to fix the link for other readers haha.

Thanks for mentioning that too. 🙂

I realized it about an hour ago, but am so delighted you’re reading. And yes, it’s kinda a story of breadcrumbs.

Dear Mija, I’m absolutely enthralled with the story, especially the pre-war London subplot, which is becoming the main plot or so it feels.

Two part question: is it a part of a future book, just curious? Kathryn usually asks this question. Also, was it on her linky link Saturday thingy? I think that’s how I came across your blog.

I’m so glad you’re enjoying it. I think it was on the link-y thing, yes.

I’ve got a post I’m working on that explains some of where this is coming from — but, not to tease, there’s a twist that needs to happened first. Book… hmmm. I’ve never considered writing a novel, but Paul asked me about that just yesterday, so, well, maybe? For now, I don’t know but it’s flattering that it’s coming off that way.

I will say WW2 (the European end) has been an ongoing interest of mine since I was 9 and someone gave me The Diary of Anne Frank for Christmas… along with my first diary, which in retrospect, bodes. It was an easy interest to have because both my parents were born the year after the war ended and both had always read fiction and non-fiction about it so there were a lot of books floating around. That they let me read anything I wanted, which included some pretty adult stuff (like Rise and Fall of the Third Reich when I was still in elementary school) is something I’ve always been grateful for – I read some total trash too.

Thank you too for the correction (warning – I’ve got a thing for pedants so I may fall in love with you while you become annoyed with me) and for pointing out issues with the font. I agree btw; it is harder to read than it should be. When I started Lady de Vries’ letters with the headmaster, I hadn’t planned for her handwriting to be quite so central. I do know it’s hard to read, which is why she’s suddenly got a typewriter for the reports. I’ll put finding a new font for her on my “to do” list. Google Fonts is SUCH a rabbit hole. Oddly they’re not categorized in a way that allows searching for “a cursive font for someone who was educated at an all-girls boarding school in the 1920s and 1930s.

Beware, you got yourself a different kind of reader, as observant as Honour, I hope…

I really enjoy reading the “handwritten” notes but one font, the green writing of her journal, sent me to the hills. It might be just me or my old glasses, so i turned to the plain text version, just for that section and then I read it to the end. Lo and behold, I found something that was in the handwritten section but not in the plain version, a very memorable phrase:

The room was full of tired men, congratulating one another on their illusions of peace when all are hearing the hoofbeats of war..

Fixed! Thank you!!

I’ve said for some time this project calls out for novelization. Once you have it completed (well, once you are done, which is not necessarily to say once it is finished, which a story like this may never be) all you’d need would be organizational editing to have a fine book.

Your comment above, that you have an affection for pedants, put me in mind of my lovely bride in particularand TTWD in general. As for us, both of teachers (she a master of the craft), both of us previously editors, me an attorney — truly a match embracing pedantry. And nothing is more particular about every little detail than is TTWD. “No, not THAT hairbrush.” “Yes, THAT skirt, but two inches longer.” Calling it “her bottom.” Perfection. Calling it “her butt.” Scene ruined.

Thank you so much, JAB! Yes, pedantry is definitely a thing. Somone seeing me, noticing my mistakes, thinking something is good but could be better. It’s not an accident that the first Pablo and Mija story, Paul’s gift to me only a month after we’d started corresponding, was “Spelling.” It was a brave thing too because sometime someone pointing out my mistakes makes me embarrassed and, for shame, quite testy.

For those of you who haven’t been around since it was posted on alt.sex.spanking in 1997, it’s here:

https://mijasroom.net/library/stories/spelling-1997-by-paul/

He wrote it by collecting a number (certainly not all) of the spelling mistakes I made in my early newsgroup posts and using those in the story. That Christmas he gave me a dictionary which we used the first time he visited in a way not unlike our fictional selves used in the story.

Thrilling.

Being told this could be a novel is really humbling. It’s been way too busy here (that part of the semester) but I’ve been doing research for the past week trying to make sure the timeline is reasonably accurate.

Becca, I also haven’t forgotten about the font issue – Honour will have a better font soon. I promise.

Everyone:

1. I wrote this planning and hoping others will decide to play in the world or make suggestions about what might happen next. If you write stories from it (how flattering!) I will post them or, if they’re on your own site, link to them here.

2. My kink email address is active again! It’s now : ** mija (at) thetreehouse (dot) net ** <- you'll need to put the pieces together.

3. Hopefully I'll be able to get the next installment up by Monday.

Coming back to these previous episodes after starting down the rabbit hole of the Kelley-de Vries correspondence, things are becoming a bit clearer to me. This “game” that Ned has been training her for in person continues through correspondence. Feigning ignorance is always an excellent ruse to obtain information from those who are always willing to talk. I suspect Honour (or is it Honor? – her name is spelled differently in the lists of posts, I noticed) honed her art on Lady Fenton and later started working on Miss Kelley, using their shared Saint Clare’s history as an entry point.

Also clear to me is how much Inez has become her mother’s daughter (no doubt by design and instruction). She has the makings of an excellent spy.