7 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

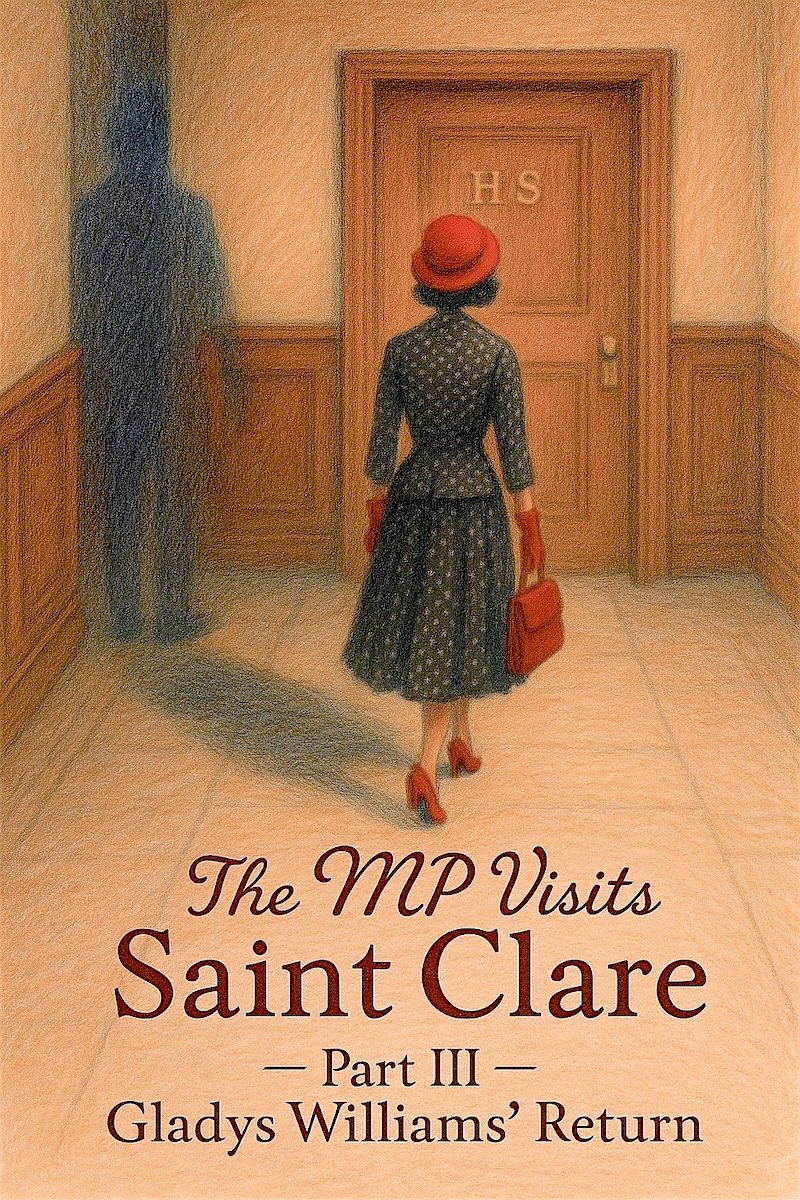

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues

Earlier instalments:

- Prologue – 11 July 1955

- Part I – 8 – 12 July 1955

- Part II – 12 July 1955 (earlier)

- Part III – 12 July 1955

Further particulars may be found in the Foreword.

This sequence draws from the Charrington Papers and the less officious corners of Saint Clare’s—those neat staff reports never meant to withstand scrutiny; the household logs written with a pointed, domestic hauteur; and the diaries, margins, and illicit notes in which the girls record rather more than their elders imagine. Some documents are respectably typed. Others arrive in the swift, unsteady cursive of someone writing under pressure, or in a place she very much oughtn’t be.

Readers are invited to take up the archivist’s task, and the investigator’s pleasure, of weighing the School’s polished accounts against the smudged, contradictory recollections of those who actually lived the day. Much will be implied. Little will be stated outright. And attentive readers may notice that Miss Gladys Williams’s file, though she left Saint Clare more than five years ago, has begun to grow again—curiously, and on no official authority whatsoever.

The archive remembers. And so, of course, does Inez.

Comments are warmly welcomed. While I enjoy seeing them on Bluesky and Twitter, those left here become part of the archive proper, where they may—quietly—shape what follows.

Foreword – Archivist Note

Among the curiosities preserved in the Saint Clare papers, few are as revealing—or as inadvertently scholarly—as the diary entries of Miss Anne Kelley, English Mistress. Her account of 12 July illustrates a trait well known among school staff but rarely acknowledged in print: the ability to listen with perfect composure while appearing to be engaged in productive labour.

Among the curiosities preserved in the Saint Clare papers, few are as revealing—or as inadvertently scholarly—as the diary entries of Miss Anne Kelley, English Mistress. Her account of 12 July illustrates a trait well known among school staff but rarely acknowledged in print: the ability to listen with perfect composure while appearing to be engaged in productive labour.

This instalment reproduces her notes from that afternoon, recorded with the precision of a woman trained to mark essays, spot inconsistencies, and deduce motive from grammar alone. Her vantage in the outer office afforded her a position both enviable and unenviable: she was neither participant nor bystander, but something closer to a reluctant ethnographer with unusually good access.

Readers familiar with the preceding parts (particularly the testimonies of Miss Williams) will find here a corrective of sorts. Where Gladys dealt in melodrama and sensation, Miss Kelley offers structure, sequence, and the kind of politely shaded inference that could, if one wished, form the basis of a conference paper on mid-century educational discipline.

What follows is her account: measured, attentive, and unintentionally comprehensive. It is a rare look at how a seasoned member of staff interprets a scene that most schools prefer to consign to institutional memory rather than institutional record.

From the Journal of Miss A. Kelley

12 July 1955

An extraordinary scene in the Head’s office today. I shall write it down in detail if only to convince myself it truly happened.

I was meant to be correcting essays in the outer office, though in truth I had half an ear cocked to the corridor. One learns early at Saint Clare’s that most essays will wait, but a first-class opportunity to eavesdrop will not.

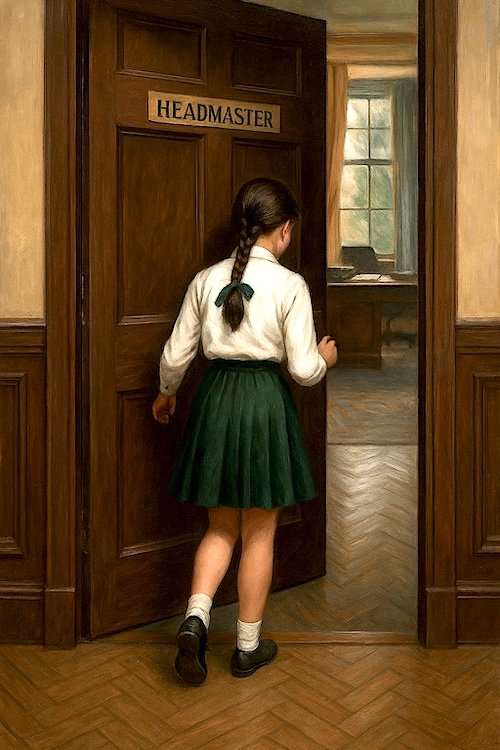

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

With that cheerful blessing, we arrive at 12 July, a date that would prove no gentler for anyone involved.

With that cheerful blessing, we arrive at 12 July, a date that would prove no gentler for anyone involved.

And we’re back in 1955. Sorry about the time traveling. We will get back to Ned and Honour soon.

And we’re back in 1955. Sorry about the time traveling. We will get back to Ned and Honour soon.  Friday, 8 July 1955

Friday, 8 July 1955

Foreword

Foreword