0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

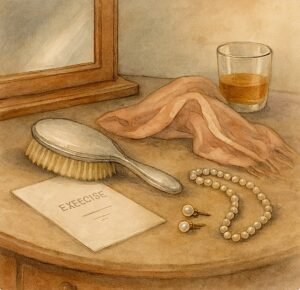

I wrote this two weeks after surgery (more on that later) as I sat in bed crying because the news sucks, there was another form to fill out, I found out I couldn’t go to the Vegas party this weekend, and plus I couldn’t wash my hair. I formatted it as an image to post on Twitter and Bluesky, but then forgot to do it.

It really is, still, shocking to me that whether or not I’ve eaten and what I’ve eaten has such an effect on me, especially since I’m rarely hungry. I know I’m not alone in this. I have a friend who told me that whenever she and her dad would be in a discussion/disagreement and it started to get heated her dad would say something like “I’ll continue this after we’ve both eaten an apple.” This seems like a really good idea.

Since I’m only cooking for me these days and I’m home recovering I can forget to eat or remember but it seems like too much trouble / easier just to go to sleep. Especially if, say, I’ve been writing some Inez stuff or reading or practicing calligraphy. Just about anything is less boring than cooking1When I say cooking here I mean the day-to-day keeping myself fed kind of stuff. More elaborate cooking and baking is different and interesting. and eating.

Clearly my more responsible inner self needs to keep better tabs on what I’m eating when because there’s always time for a protein shake.

Text version for those who use Readers:

Self-Parenting

Me: I’m sad & everything sucks.

Me: Nothing will ever be right again.

Also Me: That’s terrible. Have you eaten?

Me: You think that’s why I’m sad? Food?

Also Me: Was it dinner last night?

Me: <rolls eyes> Lunch.

Also Me: But I made dinner.

Me: It’s still in the microwave.

Also me: Eat something now. You’ll feel better.

Me: I won’t. I’ve just eaten something. You’ll see.

(15 minutes & one protein smoothie later)

Me: Shit.

Also me: What?

Me: Everything still sucks but I’m okay.

~by Mija

- 1When I say cooking here I mean the day-to-day keeping myself fed kind of stuff. More elaborate cooking and baking is different and interesting.

The Archivist Gets the Last Word:

The Archivist Gets the Last Word:

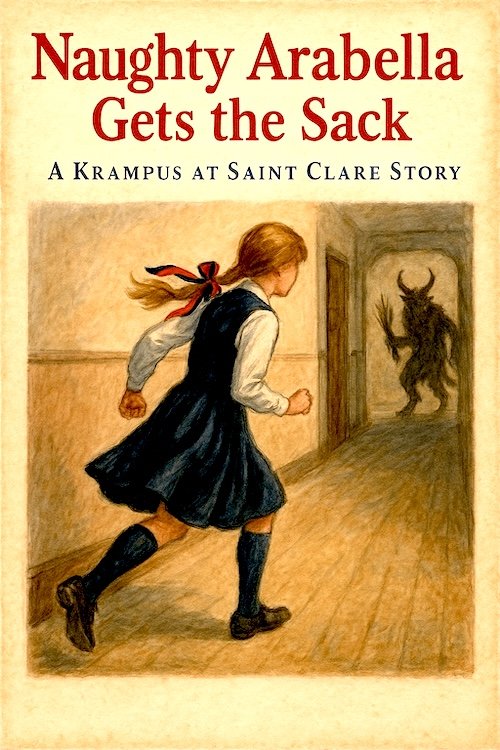

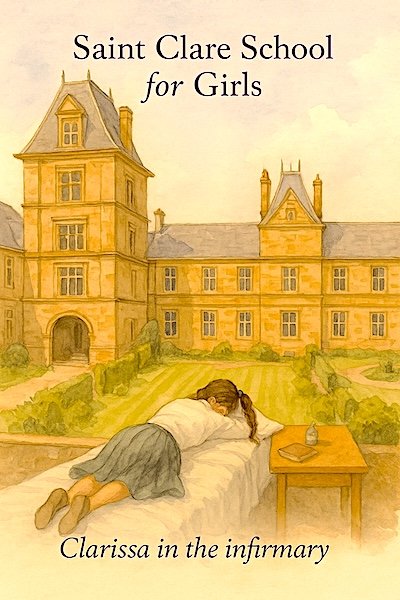

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

Introduction

Introduction

This tale follows

This tale follows  (This part of the text comes from the end of

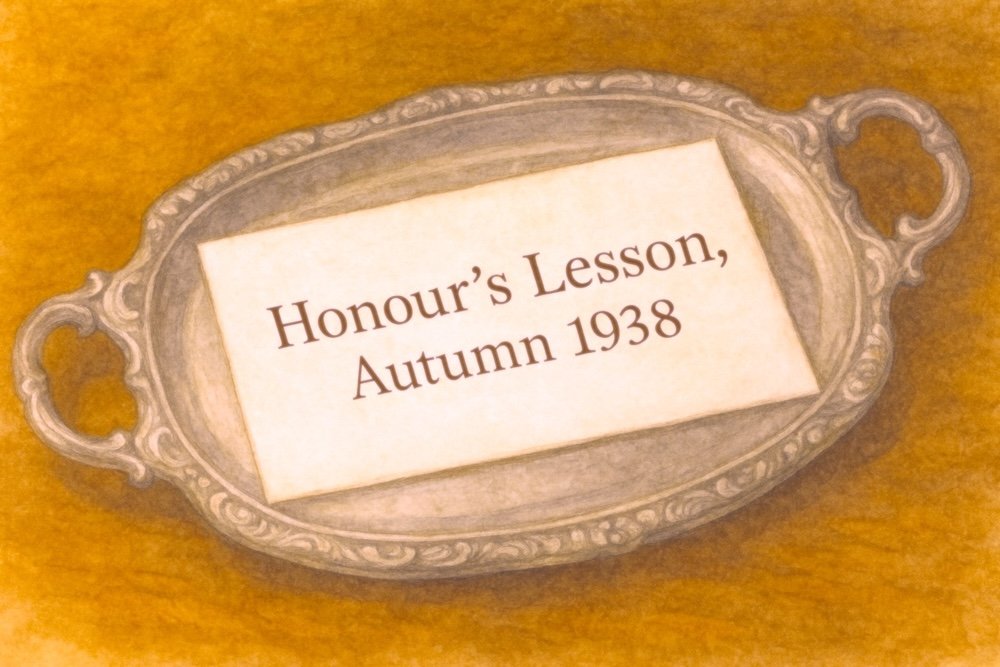

(This part of the text comes from the end of  He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but.

He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but.

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.