0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

Introduction:

What began as a playful observation on Bluesky (that the name “Arabella” is destined to belong to the naughtiest girl in any school) has now grown into a small constellation of stories. Mine took a folkloric turn with Saint Clare’s and Krampus; this one, shared here today, takes its own wonderful path.

So enjoy this spirited take on Arabella: The Patron Saint of Bad Behaviour Everywhere written by a fellow participant in the thread who wishes to remain unnamed, at least for now.

Again for clarity – this is a guest contribution to that Arabella-led challenge. It is entirely outside the Saint Clare universe. This is simply a wonderfully cheeky contribution inspired by the same mischievous spark: the girl Arabella whose name alone hints at trouble. I’m so delighted to be able to share it.

Guest Story – Reposted Here with the Author’s Permission.

Naughty Arabella’s Just Desserts

Was it even real? Did that really just happen?? I slid my claw along the gilded edge of the envelope in my pocket as I threaded my way through the throngs of teenagers toward Mr Climbover’s class.

It felt real enough. But it could be a trick. Arabella had never noticed me before – not that I minded but – she was the coolest girl in school, everyone knew her name and when she walked through the halls the other kids made space for her and her trail of lackeys trying to kiss her perfect butt.

Most of us dragons, if we bother to shapeshift, stick with other animals. It’s easier. Not her.

Arabella stayed in her human form indefinitely, as far as anyone knew. There were even some rumors she was actually human who somehow sneaked into the conclave’s boarding school – how else did she get the form so perfect??

All of her lackeys tried to mimic her, of course, with varying degrees of success. Her simpering entourage looked more like humans going trick or treating. Cheap costumes even. None of us dared say anything because the comet they followed could make or break anyone’s social standing with a single sneer.

As I settled into the hard wooden student desk, I reached for my stashed envelope again. I slid it out of my pocket and smoothly slipped it into my history text book on my desk. Its golden filigree edge peeked out of the heavily thumbed pages, a sparkle of hope for my own social standing.

An invitation to Arabella’s birthday party! With my name on it!

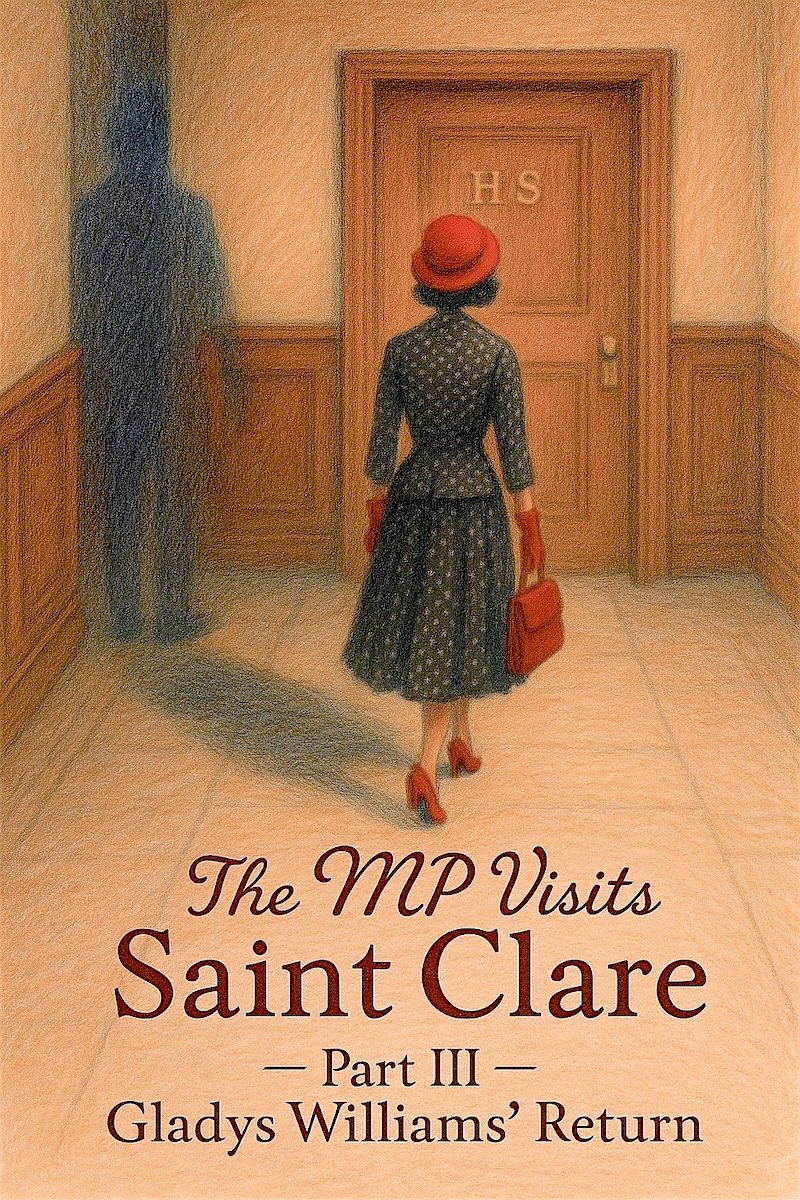

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues Among the curiosities preserved in the Saint Clare papers, few are as revealing—or as inadvertently scholarly—as the diary entries of Miss Anne Kelley, English Mistress. Her account of 12 July illustrates a trait well known among school staff but rarely acknowledged in print: the ability to listen with perfect composure while appearing to be engaged in productive labour.

Among the curiosities preserved in the Saint Clare papers, few are as revealing—or as inadvertently scholarly—as the diary entries of Miss Anne Kelley, English Mistress. Her account of 12 July illustrates a trait well known among school staff but rarely acknowledged in print: the ability to listen with perfect composure while appearing to be engaged in productive labour.

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

With that cheerful blessing, we arrive at 12 July, a date that would prove no gentler for anyone involved.

With that cheerful blessing, we arrive at 12 July, a date that would prove no gentler for anyone involved.

Friday, 8 July 1955

Friday, 8 July 1955

Foreword

Foreword