0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

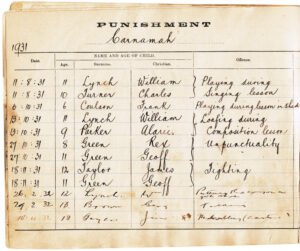

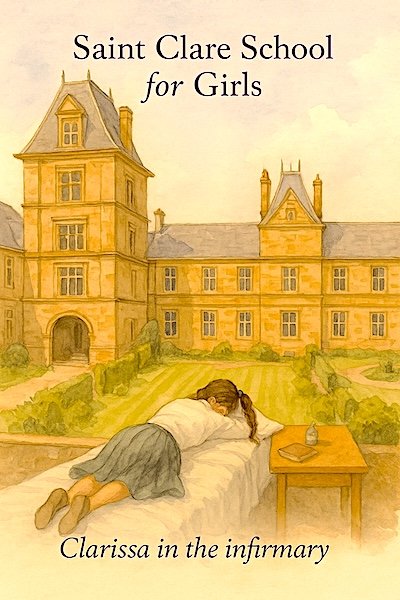

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here, and promise to respond. Moreover your ideas and reactions also join the archives, where they may quietly shape what comes next..

Archivist Foreword

The document that follows was written in the back seat of a carefully maintained Humber on the afternoon of 12 July 1955, shortly after its author had been summoned to the Headmaster’s study at Saint Clare’s. Although Gladys Williams was no longer a pupil of the school, this distinction proved to be of limited practical importance.

Readers familiar with the school story will recognise the situation without difficulty. A former girl returns, meaning well, and finds herself required to explain her conduct, to wait, and to remain present. The rules, once learned, are not easily forgotten, and are applied with particular confidence to those who ought to know better.

This entry does not attempt to set out the facts of the incident in full; those are recorded elsewhere, and in proper order. What Gladys provides instead is a running account of the afternoon as she experienced it: the Headmaster’s study, the formalities observed, the tea tray, the silences, and the journey that followed. She writes quickly, with feeling, and at some length. This too will be familiar to readers of school diaries.

With this entry, the Saint Clare record pauses. Lessons resume, bells ring, and the school continues. The account that follows travels on.

The MP Visits Saint Clare – Previously posted

Gladys’ Diary

12 July 1955

Later (the Head’s Study; continued in the car)

I won’t forget today, no matter how old I get or how many pages I scribble. Ghastly. Utterly ghastly. There were so many awful bits I can’t even decide which was the worst, nor which to write first. Now that we are back on the road I am writing as fast as I can, partly so I don’t have to look up. If I don’t look at him, perhaps Gerald won’t speak to me. I can feel him watching me over the tops of his papers, but I go on as if I were completely absorbed.

Instead of letting me slink away after that wretched drive up from London, Gerald marched us straight down the dim corridor to the Head’s study. The cabbage smell clung to the walls and our shoes echoed like a sentence already passed. He opened the door, stood back, and waited for me to go in first, as if I were being presented for inspection. We weren’t expected — not then — but he behaved as if the place had been waiting for him all along, papers under his arm, that terrible air of purpose he puts on when he’s decided something. I think Miss Kelley tried to say something, but I barely caught her eye before I was all but pushed into the Head’s office.

Mr Lewis blinked at us from behind his spectacles, plainly surprised to see a party from London descend on him without warning. Gerald merely inclined his head and said, smooth as you please, “A word, if you please.”

The Head invited us as if we had not already imposed ourselves, and then, almost absurdly, rang for a tea tray with sandwiches .

These niceties over, Gerald turned on me, using that dreadful low voice of his, the one that weighs more than shouting ever could.

“Miss Williams,” he said, quiet and clipped, “I wish you to tell the Head exactly what you have done.”

There was nowhere to look. My heart sank straight through my shoes. I am not a pupil; I have not been one for years. And yet there I stood, spluttering and stammering like a schoolgirl hauled up for passing notes. Gerald would have none of it. I had to admit everything: Clarissa’s letter with Inez’s enclosed, the request to send it on to her mother, my saying yes, my writing a cover note and posting them off to Lady de Vries. I told it in silly little scraps, and every bit felt worse once the Head had heard it. The words slid out like stones, and the room, large though it was, felt very small as the shelves of books seemed to close in around me.

When I finally finished, Mr Lewis did not address me at all, but remarked, almost to the furniture, “Ah, so that is how she knew.” The “she” was certainly not me.

Then, more formally, he straightened in his chair and addressed us both. He was polite, firm but almost apologetic, and said the School could not possibly condone letters carried privately. He paused and added (as I could have told him) that as I am no longer a student, my part in the matter was not his affair, but one to be settled between my brother-in-law and me.

Gerald nodded, but replied that he wished the matter on record, and asked that Clarissa be called.

Mr Lewis went to the door and asked Miss Kelley to have a prefect bring Clarissa to his office. We heard her give instructions to “Fairfax” — a prefect, I suppose — just as one of the kitchen maids came in with the clattering tea tray. Then, adding to the whole Lewis Carroll feeling of the afternoon, the Head apologised for the tray’s “meagre fare,” offhandedly blaming our sudden appearance for leaving the kitchen unprepared.

What followed was an extreme bout of conversational awkwardness. He talked about anything except what we were really there for: the heat, the gardens, the fête already past, the coming holidays. His small talk sounded thin and nervous to me. Gerald answered in kind, dry but courteous, as he ate sandwiches and drank two cups of tea. I never touched mine. No one seemed to notice. Everyone else was fed. The silences between the men grew longer and heavier until they felt like stones piling up. Despite the tea, my mouth was completely dry, and I contributed nothing.

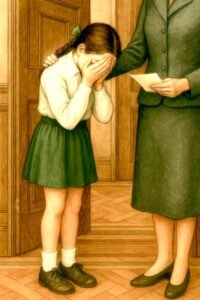

After what felt like hours, but was probably no more than twenty minutes, Clarissa arrived, walking through the doorway as if to her doom, her legs so embarrassingly bare and vulnerable in her field hockey skirt, grass stains still on her knees. I saw the shock on her face when she took in Gerald and then me, sitting there together. Her eyes were huge and round. I heard Miss Kelley say something low to the prefect as Clarissa crossed the threshold. Mr Lewis remained at his desk.

Gerald didn’t waste a moment. After the briefest of greetings, he took Clarissa through the same wretched confession he’d forced out of me, making her tell the Head exactly what she had done. My stomach clenched and I was glad I hadn’t touched the tea. I felt her eyes on me, begging for help, but I couldn’t meet them.

I won’t pretend I listened to every word. I heard her first stumbles, the brave little resolves, the determined refusal to betray Inez. Clarissa would not, could not, name her. Gerald repeated my admissions for her benefit and scolded her for involving me, his voice dry and clipped, as if this were all part of a lesson that needed to be properly understood. Mr Lewis sat very straight in his chair and said nothing, nodding only occasionally.

When it was done, the Head stood, cleared his throat, and spoke with that careful, official politeness of his, saying he was satisfied he understood the situation. He added that the School could not be party to further discussion of family discipline, and that Gerald was welcome to make use of the study. Then, murmuring something about other duties, he left the room.

The door shut behind him and, just like that, the air changed. We were alone.

Foreword

Foreword

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.

The Charrington Papers, of which the present collection forms a small but telling part [see also

The Charrington Papers, of which the present collection forms a small but telling part [see also

Based on

Based on