6 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

Foreword:

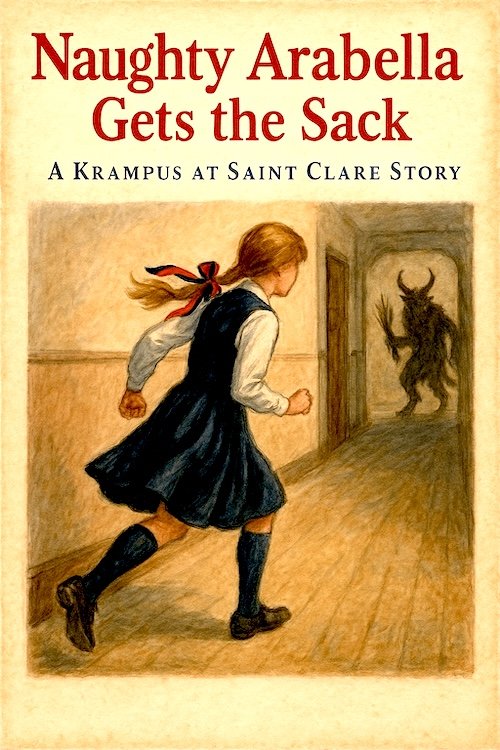

Every so often, a Saint Clare story arrives from an unexpected corner—this one came from an offhand comment on Bluesky about how “Arabella” is the name of a girl who is absolutely up to mischief. That joke blossomed into an open challenge to write a story with “Naughty Arabella” somewhere in the title.

https://bsky.app/profile/mija-again.bsky.social/post/3m754wu5vrc2n

This is my offering.

Naughty Arabella Gets the Sack – Winter 1925 at Saint Clare’s takes place firmly within the larger Saint Clare universe, but outside the Inez of the Upper IV arc. It introduces an earlier generation of girls—and a long-standing bit of school folklore involving a seasonal visitor who is, essentially, OFSTED with hooves. Krampus pays annual calls to Saint Clare’s, but this year he meets his match in Arabella Fairchild: blonde, brilliant, catastrophically charming, and overdue for supernatural accountability.

The result is part school-story romp, part institutional mythmaking, and wholly Saint Clare’s.

STORY – Naughty Arabella Gets the Sack

Chapter I – In Which Saint Clare’s Watches a Drama Unfold

Saint Clare School for Girls slept beneath a frosty moon in the winter of 1925, its chimneys puffing industriously and its corridors stretching away into dim, draughty mystery. Most of the Second Form were fast asleep in their flannel nightgowns, except for those peering nervously from their beds, listening to the unmistakable CLONK–CLONK–CLONK of something decidedly not school-sanctioned approaching.

Arabella Fairchild, however, was not in her nightgown.

Oh no.

Arabella stood at the centre of the corridor, dressed in her full uniform—immaculate gymslip, snowy white shirt, hair ribbons neat at either side of her head—because Arabella firmly believed that if one must face the supernatural, one should at least look as though one were about to captain the lacrosse team.

She was, as the Headmistress had once remarked in a despairingly admiring tone, “the sort of blonde beauty who, in six years, during her first season, will oblige her father to consider hiring armed guards1Borrowed from Terry Pratchett’s Hogfather (I think). in addition to the usual chaperones.”

Arabella knew this.

Arabella relied on this.

But Arabella’s beauty had never yet faced Krampus.

Girls Who Watched

Behind her, in the rows of narrow iron bedsteads, half the Second Form crouched behind blankets, whispering furiously.

“She’s done it again,” hissed Primrose Pembury, who had once taken the blame for Arabella’s practical joke involving a frog in the Latin master’s hat.

“And she’ll get away with it again,” muttered Clara Dawlish, who had written one hundred lines after Arabella persuaded her to switch name-tags on the exam papers.

“I’d like to see her caught. Just once!” whispered Lottie, who had been given detention when Arabella accidentally (on purpose) set off a smoke-bomb during sewing.

Little Sally Billings (who had been framed for the “ink-in-the-cocoa” incident) clutched her hot-water bottle and breathed, “Look at her! Smirking like she owns the place!”

The girls’ resentment simmered in the cold air.

This was the year Arabella Fairchild would receive her comeuppance.

They could feel it.

- 1Borrowed from Terry Pratchett’s Hogfather (I think).

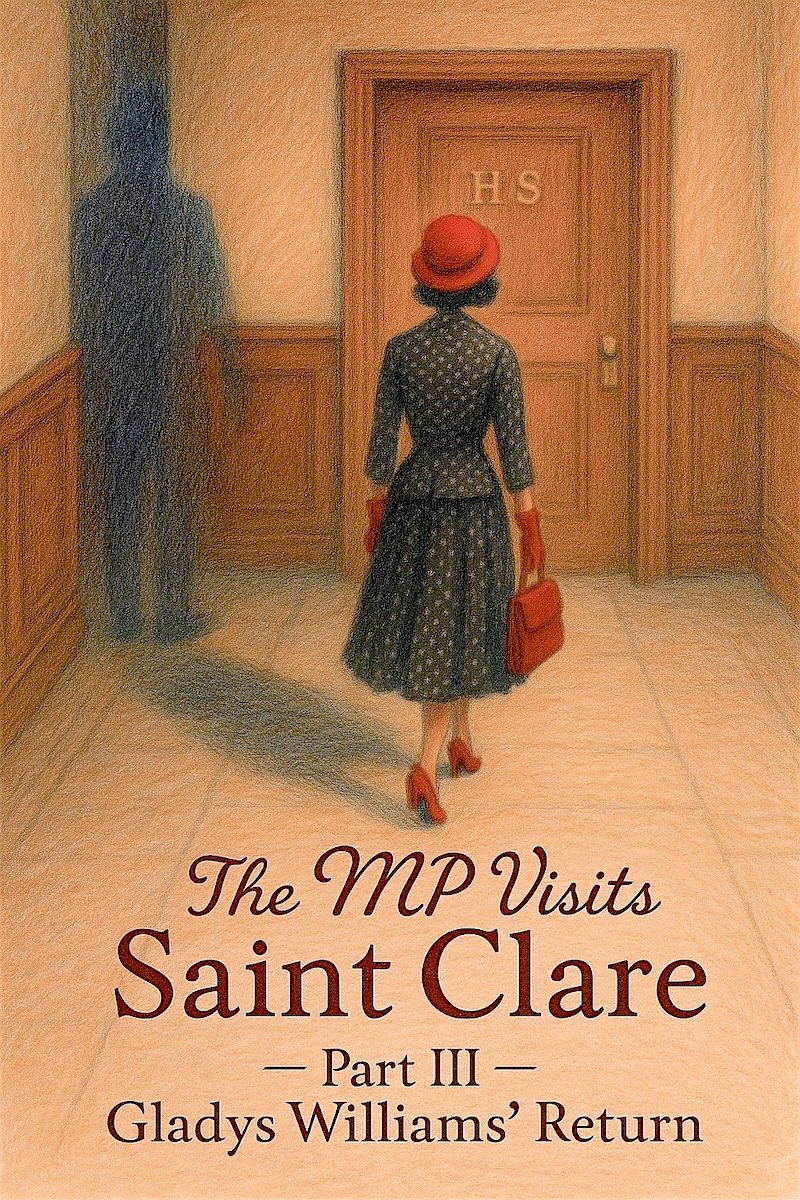

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues

“The MP Visits Saint Clare” continues Among the curiosities preserved in the Saint Clare papers, few are as revealing—or as inadvertently scholarly—as the diary entries of Miss Anne Kelley, English Mistress. Her account of 12 July illustrates a trait well known among school staff but rarely acknowledged in print: the ability to listen with perfect composure while appearing to be engaged in productive labour.

Among the curiosities preserved in the Saint Clare papers, few are as revealing—or as inadvertently scholarly—as the diary entries of Miss Anne Kelley, English Mistress. Her account of 12 July illustrates a trait well known among school staff but rarely acknowledged in print: the ability to listen with perfect composure while appearing to be engaged in productive labour.

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

Readers who have followed Part II will remember that Miss Gladys Williams arrived at Saint Clare already defeated by heat, hunger, and Mr. Charrington’s conversational style (which may be charitably described as “Hansard, but crosser”). What awaited her inside the administrative building was not respite but that most perilous of schoolgirl terrains: the dim corridor leading to the walnut-panelled study of the Head.

With that cheerful blessing, we arrive at 12 July, a date that would prove no gentler for anyone involved.

With that cheerful blessing, we arrive at 12 July, a date that would prove no gentler for anyone involved.

Friday, 8 July 1955

Friday, 8 July 1955