2 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

The story of Inez de Vries’s experiences in the summer of 1955 unfolds through a series of documents – some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained.

But Inez watches. And remembers.

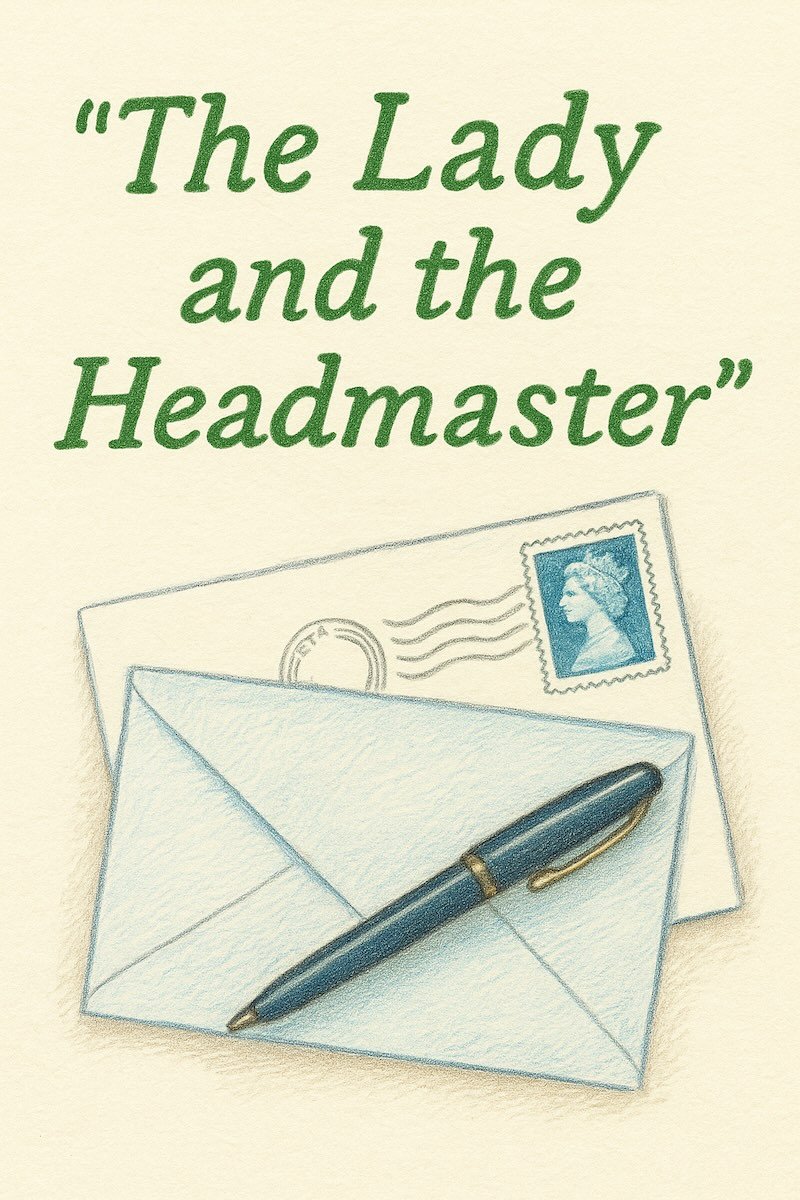

This story takes readers back to 1938 and tells the story of Inez’s parents, especially Lady Gwendolyn “Honour” de Vries, a St. Clare Old Girl who notices far more than most people realize.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here and promise to respond. Moreover your responses and ideas are included in the archives and may shift and change the story’s evolution. Also, the observant reader may notice Honour has a new font. I hope it’s more readable.

Having trouble with the handwriting? Try the plain text version.

Greystone Abbey, January 1939

If you’ve followed Honour this far – through her first lesson, her first report, and her first taste of consequence – you’ll know how easily a game of observation can become something else.

The new year finds her far from Belgravia, shut in by rain and flooded fields, testing both her wit and her husband’s patience. The guests have gone; Darlington’s lessons continue.

This story follows:

You might want to read them first.

Part Three

From the Archivist

From the Lady de Vries Collection, Blue Room Archives, Saint Clare’s School for Girls

The papers presented here form part of what is now known as the Lady de Vries Collection. Though the correspondence was originally preserved among the private files of her husband, Edmund Alexander de Vries, 9th Earl of Darlington, its preservation and eventual deposit at Saint Clare’s are due to Lady Gwendolyn Randolph de Vries herself.

The exchange of initials — D. and H. — occurs throughout. Their precise origins are unclear; however, internal evidence suggests that these letters were both a private correspondence between husband and wife and, increasingly, a record of informal “exercises” undertaken by Lady de Vries during the late 1930s.

The editors have retained the original orthography and punctuation. A few later pencil notes in Lord Darlington’s hand are reproduced in grey type. Where the line between affection and assignment blurs, readers are invited to remember that the world beyond these pages was also shifting — toward war, secrecy, and a very different kind of education.

Recovered documents: December 1938 – January 1939

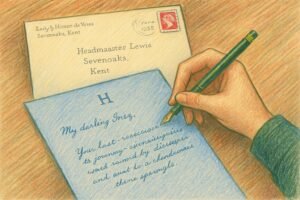

The following entries belong to that first winter at Greystone Abbey, when the young Countess was learning that discipline can be an intimacy of its own. The surviving pages are marked in her hand and his — neat pencil corrections threading through her typed reports. Both of them writing in their fountain penned script. What began in London drawing rooms now turns domestic, quieter and more perilous.

In these documents, the young Lady Honour de Vries continues working to master her husband’s “exercises”—tasks meant to discipline her curiosity and temper her impulsiveness. Yet what began as a private game of observation now reaches beyond the drawing room. A tea in Chester Square leads to the American Embassy at Grosvenor Square, and the world of polite conversation begins to tremble with rumours of the coming war.

Through reports, annotations, and private diaries, we see the gradual shaping of a partnership: his precision against her wit, his restraint against her appetite for understanding. Honour still writes to please him—but she is also beginning to see, to listen, and to turn the rules of his game to her own advantage.

The tone remains domestic, almost playful. Yet under its surface, something colder and more intricate begins to form.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I enjoy seeing them on Twitter and Bluesky, I especially love receiving them here and promise to respond. Your observations and ideas are entered into the Saint Clare archives and may subtly shift the story’s evolution.

T

T Introduction

Introduction

But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

But Inez is watching. And she remembers. This tale follows

This tale follows  – Sit where you are seen, not where you are heard.

– Sit where you are seen, not where you are heard.

(This part of the text comes from the end of

(This part of the text comes from the end of  He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but.

He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but. The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by

At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by  Trusting his indulgent understanding, Clarissa poured out her grievances to “Papa,” only to find he had abruptly transformed into “Father,” replying with all the ponderous dignity of the House of Commons. Clarissa, meanwhile, revealed a transformation of her own: the once devoted daughter emerged as a haughty, stroppy teenager, indignant at every turn and grandly refusing the hundred lines set for her. What might have remained a minor school punishment swelled into a correspondence campaign.

Trusting his indulgent understanding, Clarissa poured out her grievances to “Papa,” only to find he had abruptly transformed into “Father,” replying with all the ponderous dignity of the House of Commons. Clarissa, meanwhile, revealed a transformation of her own: the once devoted daughter emerged as a haughty, stroppy teenager, indignant at every turn and grandly refusing the hundred lines set for her. What might have remained a minor school punishment swelled into a correspondence campaign.

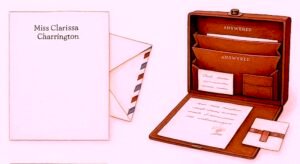

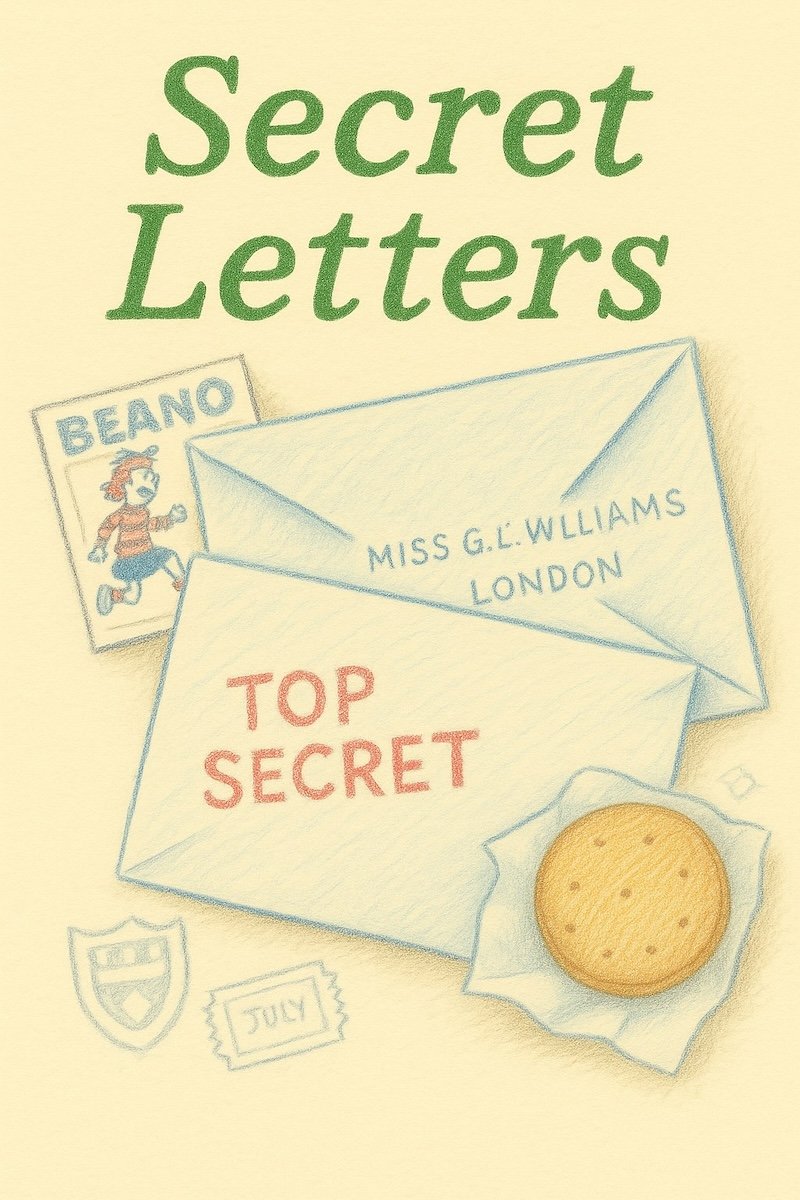

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

The

The  The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

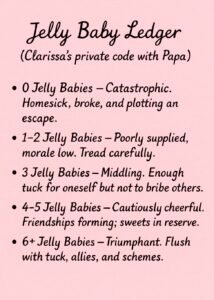

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.”

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.” Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply.

Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply. The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.

The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.