4 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

How to Read “Inez of the Upper IV”

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here and promise to respond. Moreover, as this post indicates, your responses and ideas can be included in the archives, shifting and changing the focus.

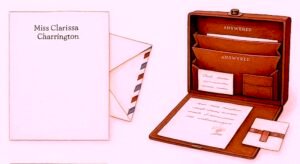

Forward to: “Clarissa’s Letters Home”

Archivist Note: These letters, begun and co-authored by reader JustAnotherBoomer, were the private correspondence between a widowed father and his fourteen-year-old daughter.

Archivist Note: These letters, begun and co-authored by reader JustAnotherBoomer, were the private correspondence between a widowed father and his fourteen-year-old daughter.

Clarissa Elizabeth Charrington and her father, the Rt. Hon. Gerald T. Charrington, weren’t writing for teachers, headmasters, politicians, or biographers sifting through archives in search of origin stories. Clarissa, newly arrived at Saint Clare’s School for Girls in the Lower Fourth during the summer term of 1955, could never have imagined these early letters home would be treasured decades later—by a daughter who may have walked the same school corridors, or found by a granddaughter after a lifetime of stories. The letters themselves spoke to no one but sat quietly for years in a forgotten tuckbox, hidden behind a yellowed copy of Jane Eyre, a single petrified Jelly Baby, and a torn wrapper from an ancient toffee.

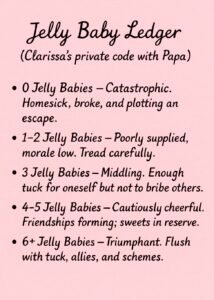

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.”

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.”

Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply.

Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply.

The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.

The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.

You may already be familiar with other records from this term—the official school reports praising Clarissa’s eloquence, the stern notes cautioning against questionable friendships, and the famously provocative essays. Yet these letters offer something different—personal, candid glimpses of Clarissa quietly shaping her conscience beneath covers and torchlight, with Inez’s daring casting long, flickering shadows across the page. In these early exchanges, we glimpse not only the schoolgirls they are—but hints of the women they will become.

The archive cannot answer every question. But the Jelly Baby count will shift, and the careful observer might notice that while Clarissa watches Inez, others have begun watching Clarissa.

Read on, gently, knowing these letters are not merely relics, but snapshots of a life becoming—quietly powerful, subtly courageous, and, well, interesting.

Having trouble with the handwriting? Try the simple font version.

Clarissa Elizabeth Charrington

Saint Clare’s School for Girls

Monday, 13 June 1955

My dearest Papa,

Thank you awfully for your last—and for the cutting about the Welsh by-election. I read the choicer morsels aloud to the dorm, and they were quite staggered that anyone could work up such a production over a rural seat. They cannot imagine why you care so much about everyone who lives there. You remain, to them, a riddle—which is wonderfully interesting. Life here is as brisk as the wind off the lacrosse pitch, and full of accidental bruises. I am in the pink, and do tell Aunt Gladys I have not been found floating in the cloister pond, nor “sent to Coventry,” however much she may expect me to be doomed to scandal.

I am currently at five Jelly Babies in the ledger.1Before she left for Saint Clare’s School, Clarissa invented a secret code based on Jelly Babies so her father would know how she was really feeling.

Your warnings about being “the new girl” were bang on—it’s rather like being dropped into a stream in full spate and told to keep up with the best swimmers. I’ve learnt to kick, and to splash a little when required. You will be relieved to know I’ve made friends—some even in the Upper School. I can’t believe I’ve only been here a week; it feels as though I’ve known her forever.

Her name is Inez, and she’s in the Upper IV. She is simply the most dazzling creature in the place—the sort I imagined when you said I could go to Mother and Auntie’s school. She drifts about as if she knows a marvellous secret. She wears her tie skew-whiff on purpose, always carries a book with the cover torn off, and can raise one eyebrow in a way that spells doom for the pompous. Perhaps a “bad influence worth cultivating”? I think so.

Yes, yes—“dazzlingly what?” Well—brave, mercurial, very wicked in her wit, and utterly unrepentant. When I first clapped eyes on her, she had ink on her collar and a split lip she refused to explain. That very day she was marched away, given the tawse on her hands, set a detention and a caning, for what the staff called “insubordination” and she called “questioning the official line.” I know what you’re thinking—but Papa, she dared—like Sir Gawain dared. She makes me sit up straighter without quite knowing why. I confess, I think of her as a modern Boudica. And yes, I may have referred to certain members of staff as “the latest and most frightful face of Roman tyranny,” but only in the literary sense—rather like Caesar’s ghost wandering into The Tempest.

We read Tacitus and Jane Eyre under the bedclothes by torchlight. Inez says Miss Temple would have liked her; I think so too—and I do like her, very much. I think you might as well, even if she struggles to keep a decent arm’s length from the punishment book.

Classes are good—especially Miss Kelley’s “Myths and Maidens.” The last essay prompt was Reconsidering the Woman at the Centre. I wrote about Helen of Troy, thinking of Aunt Gladys saying Helen’s story was nonsense unless you asked what Helen herself wanted. I enclose it, in case you care to see it.

Much love, and a smudge of ink from my disobedient left hand, which refuses to look tidy no matter how I try to force it to submit.

Your own “darling” (haha!),

Clarissa

P.S. My Jelly Baby supply is at five; however, my tuck box is down to a strip of toffee.

Rt. Hon. Gerald T Charrington, DSO, OBE, MP

White’s

15 June, 1955

House of Commons

London

Dear Clarissa:

It was with greatest pleasure I received and read (and have now several times re-read) your perfectly marvelous letter of the 14th instant. To hear you are well and enjoying St. Clare is a comfort to me.

My pleasure at receiving your letter was only enhanced by the fact that it arrived in the same post as correspondence from Mr. Lewis. He and I were certainly not insensible that the challenges any “new girl in school” faces were, in your circumstances, to be doubled by joining in the Lower Fourth and redoubled by joining in the Summer Term. But your facility at swiftly fitting into place was so notable to Mr. Lewis to compel his note to me. This report was a source of great pride for me, as it would have been for your dearest mother, I am sure. When I am wrong, I say so, and I think I must confess that you and your Aunt Gladys were right: attending St. Clare, far from bringing up painful memories around your mother’s loss, seems now like it will be healing for you. I might better have let you go sooner, but I am glad now that you both prevailed upon me in the end. (Although do not think I am apologizing in the least for that (I hope last-ever) spanking at Christmas when you utterly lost your temper over the subject. Advocacy and assertion are fine features in a young woman; stroppiness and disrespect never are, even when she has the right side of a thing.)

All the foregoing being said, though, Rissie (may I still call so mature a young lady by her nursery nickname?), I do wish to approach one other topic of perhaps less undiluted pleasure. I have told you many times that the company you keep is of crucial importance. Not because society might judge you (although it might). After all, our Lord did not scruple to keep company with vilest of sinners. But rather, and especially in a girl of your age, because of the influences, both patent and subtle, that our associations have on us. With that in mind, and while I am deeply pleased that you are making real friends, including among the older girls, I do not think it likely that a girl who was caned, tawsed and smacked all in more or less the same day can fairly be called “the most BRILLIANT girl in school!!!” And certainly not in all capital letters with three exclamation marks. I’m sure that this Inez creature has much to recommend her, but I am equally sure she is not, as you style her, “a Boudica for the modern age,” just as I am sure the school authorities in no way resemble “the new and awful face of Roman tyranny.” (Imagine poor Mr. Lewis, having praised you so handsomely in his letter, seeing himself thus described in yours.) I do not want you regarding her with such reverence when she sounds, to my reading, like more of a hoyden than a hero and no sort of martyr at all. If she was punished as you report, I’m confident those sanctions were condign and one hopes they were salutary.

So I caution you to go lightly with this Inez, if not for the sake of your better development into a St. Clare girl of whom your mother would have been proud, then–as a last resort–upon the strength of my reminder that you are not yet too old for a smacked bottom of your own, and you may expect one at home should you force the “Roman tyrants” (I confess, you did make me chuckle) into chastisement there.

But enough of me topping it the pater severus. (Has your Latin got this far yet?) You are missed every day here in our now too-quiet home and are ever in my affectionate thoughts. I look forward to your next letter and to our reunion at the end of term. Until that happy day, I am and ever remain,

Your loving father.

P.S. The essay you enclosed was fascinating in its premise and well written (although you must someday learn how “occasion” is spelt). You should be proud, as I am, of the fine mark you received. I’m not sure it is quite fair to say that Helen was “lolligaging about the beach in Troy plaiting her hair,” when the ships were launched, but your arguments for why she ought better to have commanded the fleet than wait for it were a fine reminder of what a spirited, brave and jolly girl you have always been.

P.P.S. The enclosed pound note is for deposit in your tuck shop account and should more than see you through the end of term. Do not discount the value to a “new girl in school” of the occasional (note the spelling please) and judicious distribution of sweets to her classmates .Keep me up-to-date on your Jelly Baby supplies.

Clarissa Elizabeth Charrington

Saint Clare’s School for Girls

17 June 1955

Dearest Papa,

You’ll no doubt think I’ve gotten a purple pen for my purple prose!

Thank you for your letter—which made me laugh, blush, and squirm all in turn. (Even the part about the “last-ever” spanking—though Christmas was, as I recall, a mutual loss of temper.) I do miss you, and home everyday and am looking forward to our coming holidays. It already feels I’ve been gone forever, and will never get to come back.

I am currently at four Jelly Babies.

In my dorm girls asked what party you are – I said “I don’t know” because as you said, it shouldn’t matter. Ideas are what’s important.

I’m glad the Head said good things to say, though he has not said any to me. After my stumble during the first week’s service, I rather suspect his compliments were due to my not tripping over my own hem at Morning Prayers this week. Saint Clare’s is slowly becoming more than just stone walls and schedules. Some days I even feel I belong here. But the bells are SO Loud and ring ALL the time!

Thank you for writing so gently about my friend Inez—and not simply forbidding me to speak to her. Once I sent off my letter, I half expected your thunder. Instead, I got your weather—a warning, but not a prohibition. I do take what you say seriously. I may have overstated the case in calling Inez “the most BRILLIANT girl in school!!!” (though I still privately believe it). She’s difficult to describe without sounding either swept away or subversive. But you are right—she’s no martyr. More of a trouble-magnet. You’ll laugh, but the nearest comparison I can manage is Minnie the Minx from The Beano—if Minnie spoke four or five languages and had decided opinions about the Treaty of Versailles.

I do think you’d like her if you got to speak with her. She makes life so very lively. She barrels through the corridors as if she’s late for something important, though no one quite knows what. Forever in trouble, but always with the cleverest possible reason. The staff regard her with a mixture of suspicion and fatigue; the Upper and Lower IV (mostly) adore her. Including me. And yes, she was punished most awfully the day I arrived. But Papa, there was something in her face as she was marched off—something between defiance and dignity. It was not mere cheek.

I don’t revere her, Papa—don’t worry, that is still reserved for you and God. But I see her, which is different. She says what no one else dares, but she misses certain things I think do matter—timing, tone, diplomacy. If she’s Boudica, she’s still looking for a Roman road to burn. But I prefer to find the ones worth keeping open.

She makes me think, and that’s not nothing. Perhaps it is my part to listen to girls like her and turn their thunder into music. You once told me “the best leaders borrow thunder and return it as weather.” I think Inez is thunder, and I should like to learn to be her weather.

I’m not about to take up arms against anyone —I still believe in what the school might be, and, more practically, have no wish to feel even ONE cane stroke. She showed her marks to our dormitory and we all gasped. But Inez is showing me what it is she believed worth it. If I’m clever, I can learn to walk that line—holding my faith while keeping company with those who ask sharper questions. Was it you who once said that courage isn’t always loud—that sometimes it’s simply staying in the room with someone who makes everyone else tremble a little? I don’t follow her footsteps, but I do watch the direction she points. You were right to advise caution, and you CAN trust me.

Before I forget—she asked me something curious the other day, offhandedly, as she does all important things. Inez—her surname is de Vries, did I tell you?—asked if I was YOUR Clarissa. When I said yes, she nodded as though filing it away for later, and remarked that you might know her father. I had no idea what more to say, so I nodded back.

Miss Kelley returned my essay with a red line under “lolligaging” and a mark that looked like a faint sigh in the margin. But she called the argument bold and “well though strangely evidenced” which I am choosing to take as praise. I enclose it, spelling errors and all. Perhaps it will make you smile—or wince. Or both.

Must dash—there’s a House kit inspection before tea, and Cook’s hinted there might be actual butter in the scones if the delivery lorry isn’t late.

A. ll love from your left-handed and slightly ink-stained daughter,

Rissa

P.S. I am using my right hand for formal exercises, as ordered. But my left is still the one that knows how to think.

Rt. Hon. Gerald T Charrington, DSO, OBE, MP

White’s

21 June 1955

My dearest Clarissa,

Your letter was a joy, as always, to receive—full of keen observation, unexpected simile, and that particular mixture of charm and precision that marks all the best kind of mischief. I laughed aloud at your Minnie the Minx comparison and was glad to read you’re keeping your wits about you while others seem content with starch and timetables. I read it twice before lunch and then once again after, with a stronger cup of tea. You’ve brightened your old papa’s day. I enclose a package with the Beano Summer Annual in thanks.

I did take note of the name you mentioned: Inez de Vries. It stirred something—perhaps a conversation half-remembered or a place setting at a dinner I wasn’t meant to attend but somehow did. If memory serves there was a de Vries involved in diplomatic circles during the final stages of the war—Eastern postings, I believe. That kind of work tends to leave few footprints and fewer friends. I may have crossed paths with him at one of the Foreign Office evenings. Or perhaps only heard his name murmured in the corridor outside the Cabinet Room.

As for her mother—. Lady Gwendoline Justine Honor de Vries nee Randolph, assuming it is the same lady, has always had perfect manners and still more perfect timing. She could end a conversation with a compliment and leave you wondering why you felt bruised. That sort of talent rarely fades with marriage. It would explain the letter-perfect bearing you described. Gwennie was the sort who could thread a needle while fencing. I imagine her daughter might have the same unerring grace, though, perhaps, not the same aim. Based on this, your Inez comes from sharp stock. Children raised at the edges of big, complex lives often learn too early to see things others miss. Sometimes they carry the world on their shoulders before anyone’s notices or tells them to put it down.

You’re right to be interested, and still more right to be wary. Inez sounds like the kind of girl born to notice weaknesses in a wall and clever enough to use them to pass through unseen. Whether she means harm or simply prefers her own way may not matter to the wall. Trust your instincts, my dear. Keep your heart open and your eyes sharper. And remember: influence can be inherited or earned—but the ones with both tend to be the ones to watch.

With pride and affection,

Your father

P.S. Your essay is quite something and I enjoyed reading it. You have your mother’s fire and your own kind of steel. I suspect Miss Kelley’s “ambitious” was offered with a raised eyebrow and the faintest smile. That’s as good as it gets in most staff rooms.

- 1Before she left for Saint Clare’s School, Clarissa invented a secret code based on Jelly Babies so her father would know how she was really feeling.

My goodness, what fun.

First, let’s be clear: Since Gutenberg set up shop, the title of “co-author” has never been so generously bestowed. It would be less hyperbole to say John Jay “co-authored” The Federalist Papers. So the readers are clear, I contributed a draft of Gerald’s first letter, which Mija edited deftly and from which she then reflected backwards and forwards in time, greatly expanding my oblique hints into a rich, densely detailed story and summoning characters fully drawn in just a few words. Meanwhile, she leveraged Gerald and Clarissa’s correspondence to continue to reveal the complex and compelling Inez, at the center of the tale.

I simply love this entire project. I’ve been a newspaper reporter and then trial lawyer for my professional career (with visits to The Academy) and so have always made my living constructing meaningful and persuasive narratives from fragmented, often random, bits and pieces of the truth on the ground. Seeing this done here, in the manner of a textured history put together from primary sources, touching as it does on deep elements of TTWD, is proving to be a joy.

Mija, I’m working on one more letter. Correspondence from Gerald to his daughter of a less happy sort, sent in response to her (and, sadly, the school’s) report of a less happy set of circumstances involving the two girls, with DECIDELY less happy results for Clarissa. (She’ll be lucky to stand (and I do mean stand) at two Jelly Babies.) I’ll send it along when I’ve drafted it and you will be free to use it if, as, when or never, as may best serve the project.

Meanwhile, let me encourage your readers to comment and participate here, as that is not only fun, but meat and milk to a fine creator such as you are.

This was great! Love it.

If I may offer one small critique – while the father’s handwriting is very grand, it is a touch difficult to read where the loops and curls come close together. Though perhaps that’s w mobile phone issue.

Thank you for an amazing read and interesting new characters. 😊

Hi Jon, Thank you and I have no problem with you pointing this out — it’s something I’ve wondered about as when I teach I’ve often come across students who can’t read cursive at all, let alone a font with a gothic italic. I’m a bit limited in terms of Google’s selection of masculine cursive fonts so what I’ve done is added a link to a plain text version of the letters. I’ll do this going forward and will go back as well as soon as I can. Thanks very much!

https://mijasroom.net/library/stories/jelly-baby-letters-plain-text/

That’s very kind of you. It is easier to read on my computer screen as opposed to my tiny phone screen, but a plain text version is appreciated.