3 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

Introduction

The papers gathered here belong to the wider Saint Clare archive and sit alongside the documents already familiar to readers of the Inez de Vries sequence: detention essays, staff memoranda, prefect minutes, household logs, and the private writings that have a habit of surviving precisely because no one quite knows what to do with them.

The papers gathered here belong to the wider Saint Clare archive and sit alongside the documents already familiar to readers of the Inez de Vries sequence: detention essays, staff memoranda, prefect minutes, household logs, and the private writings that have a habit of surviving precisely because no one quite knows what to do with them.

The Seduction of Anne Kelley draws from the Kelley–de Vries correspondence, preserved in the Blue Prefect Study papers, where material that is neither wholly private nor entirely official has long been kept. You will find letters meant to be burned, copies retained “for reference,” and drafts that should by rights have been torn up but were instead saved, retied, and filed under headings of optimistic vagueness. Some pages are neatly typed, as though the truth might be made more palatable by proper margins. Others arrive in the swift, unsteady cursive of someone writing under pressure, or in a place she very much ought not to be.

The sequence opens, deliberately, near the middle of things. In July 1955, Anne Kelley, a Saint Clare’s English mistress, writes a letter to “Gwennie” with the ease of long practice. Only afterward do we return to the beginning, to see how their correspondence formed, why it was encouraged, and what it made possible.

Readers are invited to take up the archivist’s task, and the investigator’s pleasure, of weighing what people say they intended against what they were, in fact, doing. Much will be implied. Little will be stated outright. Those accustomed to the School’s “special friendships” may notice familiar patterns resurfacing in adult form: the same hierarchies, the same alliances and intimacies, and stakes rather higher than dormitory gossip ever required.

These letters trace the development of that correspondence, from proper parental enquiry to something more deliberate, conducted quietly over time in the familiar idiom of the School. For those who prefer their archives with a guide, a brief introduction to the principal actors has been provided, in the manner of a proper dramatis personae. The archive remembers. And so, of course, does Inez.

Comments are warmly welcomed. While I enjoy seeing them on Bluesky and Twitter, those left here become part of the archive proper, where they may quietly shape what follows. I cannot promise the archive is obedient, but it is, as ever, attentive.

Archivist’s Foreword

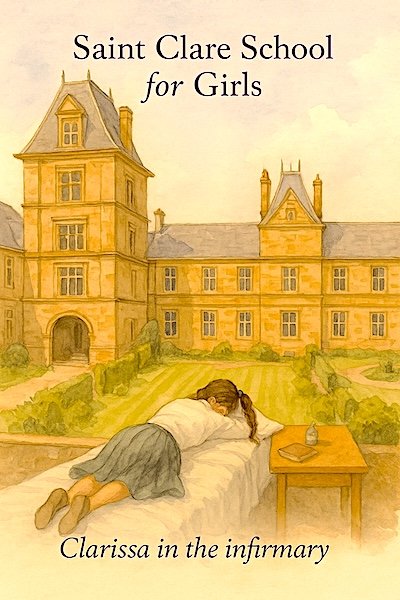

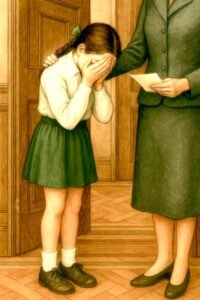

This document, a letter from Anne Kelley, English teacher and housemistress for Inez and Clarissa, is written on Saint Clare’s letterhead and dated 12 July 1955. The reader will recall that 12 July 1955 was the day of MP Gerald Charrington’s visit, the sort of day the timetable insists is perfectly ordinary right up to the moment it becomes legendary, and when poor Clarissa learned that a man may promise to “conclude matters at home” while concluding them perfectly well in the Headmaster’s study. Despite the letterhead, this document is not a school report. It is not, in fact, an official communication at all. It is, strictly speaking, the sort of thing the writer hopes will be burned, mislaid, or eaten by the dog before anyone has the bright idea of filing it.

Fortunately for this archivist, and for you, dear reader, it was saved and filed.

The reader may recall that earlier, in Miss Kelley’s own journal, there is a line about “enough of this ink-spilling” and the need to “take up a clean sheet” in order to write to “Gwennie” about the day’s events.[1] This is that clean sheet, or at least one of them. Saint Clare’s, as we are learning, produces duplicates with the same ease it produces contradictory rules.

The letter was later found among Lady Gwendolyn’s papers in the Blue Prefect Study archives, as part of a bundle tied with green ribbon and optimistically labelled “Williams, G., Misc. 1955.” It is marked, in spirit, for your eyes only, which in any archive, even Saint Clare’s, is less a boundary than an invitation.

[1] One further note, offered as an observation rather than judgement: the salutation of “Gwennie” is not the sort a young schoolmistress generally addresses to either a countess or the mother of a pupil. And yet Anne Kelley is generally so very professional and proper. Curious, that.

Saint Clare’s School for Girls

12 July 1955

My dear Gwennie,

You asked to be told when anything material touches Clarissa; what follows is for your eyes only. I was correcting essays at the outer desk by the Head’s study when Mr. Charrington arrived with Miss Gladys Williams. I will not pretend I did not linger. One can hear perfectly well from that chair if one is so inclined. (more…)

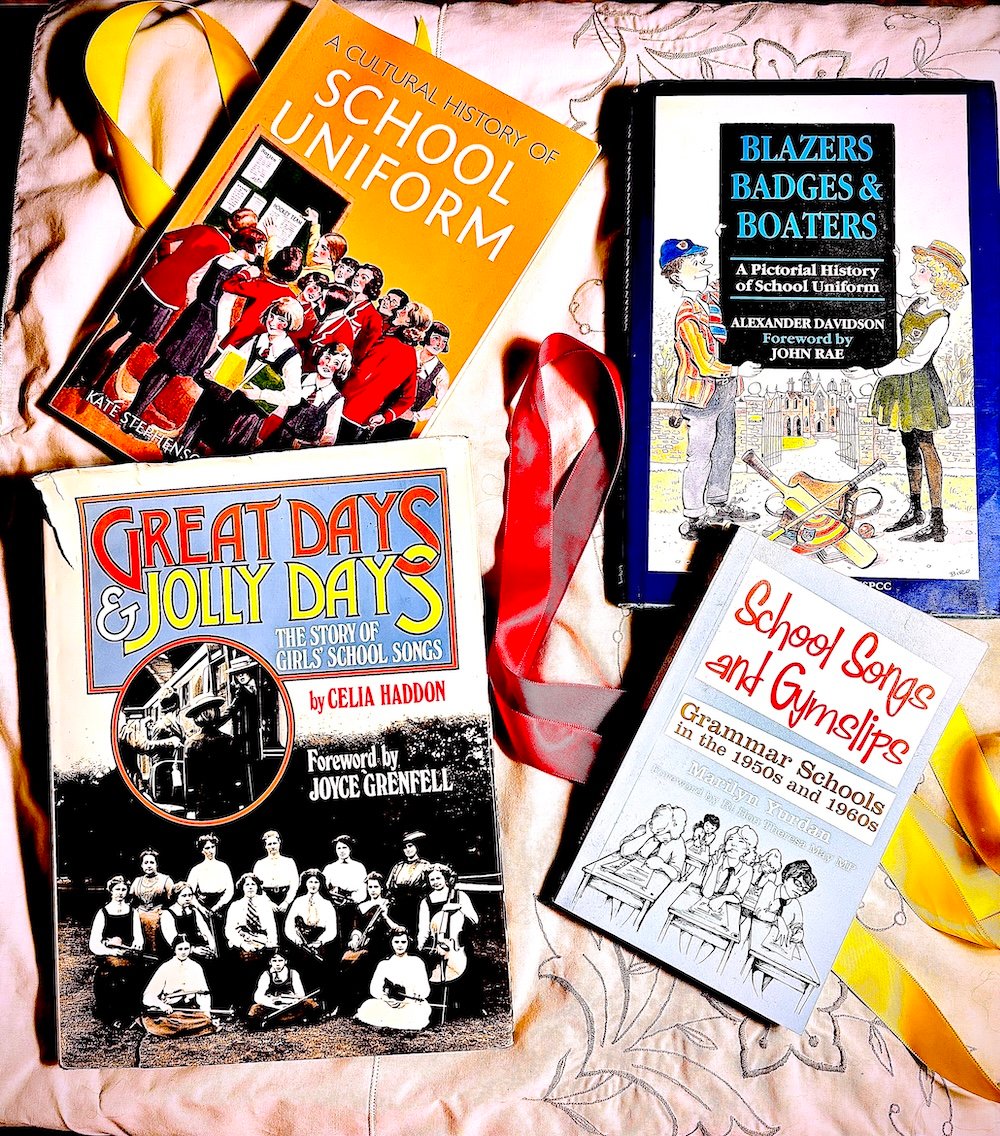

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. The

The