6 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

Foreword:

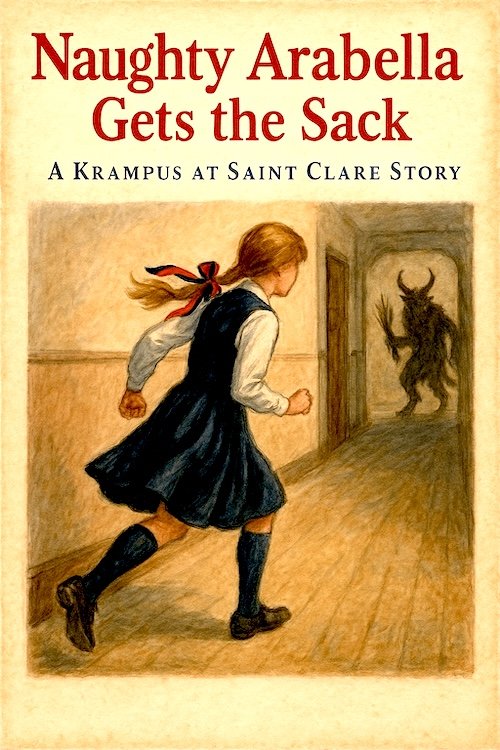

Every so often, a Saint Clare story arrives from an unexpected corner—this one came from an offhand comment on Bluesky about how “Arabella” is the name of a girl who is absolutely up to mischief. That joke blossomed into an open challenge to write a story with “Naughty Arabella” somewhere in the title.

https://bsky.app/profile/mija-again.bsky.social/post/3m754wu5vrc2n

This is my offering.

Naughty Arabella Gets the Sack – Winter 1925 at Saint Clare’s takes place firmly within the larger Saint Clare universe, but outside the Inez of the Upper IV arc. It introduces an earlier generation of girls—and a long-standing bit of school folklore involving a seasonal visitor who is, essentially, OFSTED with hooves. Krampus pays annual calls to Saint Clare’s, but this year he meets his match in Arabella Fairchild: blonde, brilliant, catastrophically charming, and overdue for supernatural accountability.

The result is part school-story romp, part institutional mythmaking, and wholly Saint Clare’s.

STORY – Naughty Arabella Gets the Sack

Chapter I – In Which Saint Clare’s Watches a Drama Unfold

Saint Clare School for Girls slept beneath a frosty moon in the winter of 1925, its chimneys puffing industriously and its corridors stretching away into dim, draughty mystery. Most of the Second Form were fast asleep in their flannel nightgowns, except for those peering nervously from their beds, listening to the unmistakable CLONK–CLONK–CLONK of something decidedly not school-sanctioned approaching.

Arabella Fairchild, however, was not in her nightgown.

Oh no.

Arabella stood at the centre of the corridor, dressed in her full uniform—immaculate gymslip, snowy white shirt, hair ribbons neat at either side of her head—because Arabella firmly believed that if one must face the supernatural, one should at least look as though one were about to captain the lacrosse team.

She was, as the Headmistress had once remarked in a despairingly admiring tone, “the sort of blonde beauty who, in six years, during her first season, will oblige her father to consider hiring armed guards1Borrowed from Terry Pratchett’s Hogfather (I think). in addition to the usual chaperones.”

Arabella knew this.

Arabella relied on this.

But Arabella’s beauty had never yet faced Krampus.

Girls Who Watched

Behind her, in the rows of narrow iron bedsteads, half the Second Form crouched behind blankets, whispering furiously.

“She’s done it again,” hissed Primrose Pembury, who had once taken the blame for Arabella’s practical joke involving a frog in the Latin master’s hat.

“And she’ll get away with it again,” muttered Clara Dawlish, who had written one hundred lines after Arabella persuaded her to switch name-tags on the exam papers.

“I’d like to see her caught. Just once!” whispered Lottie, who had been given detention when Arabella accidentally (on purpose) set off a smoke-bomb during sewing.

Little Sally Billings (who had been framed for the “ink-in-the-cocoa” incident) clutched her hot-water bottle and breathed, “Look at her! Smirking like she owns the place!”

The girls’ resentment simmered in the cold air.

This was the year Arabella Fairchild would receive her comeuppance.

They could feel it.

- 1Borrowed from Terry Pratchett’s Hogfather (I think).

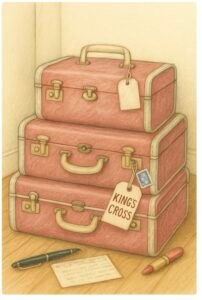

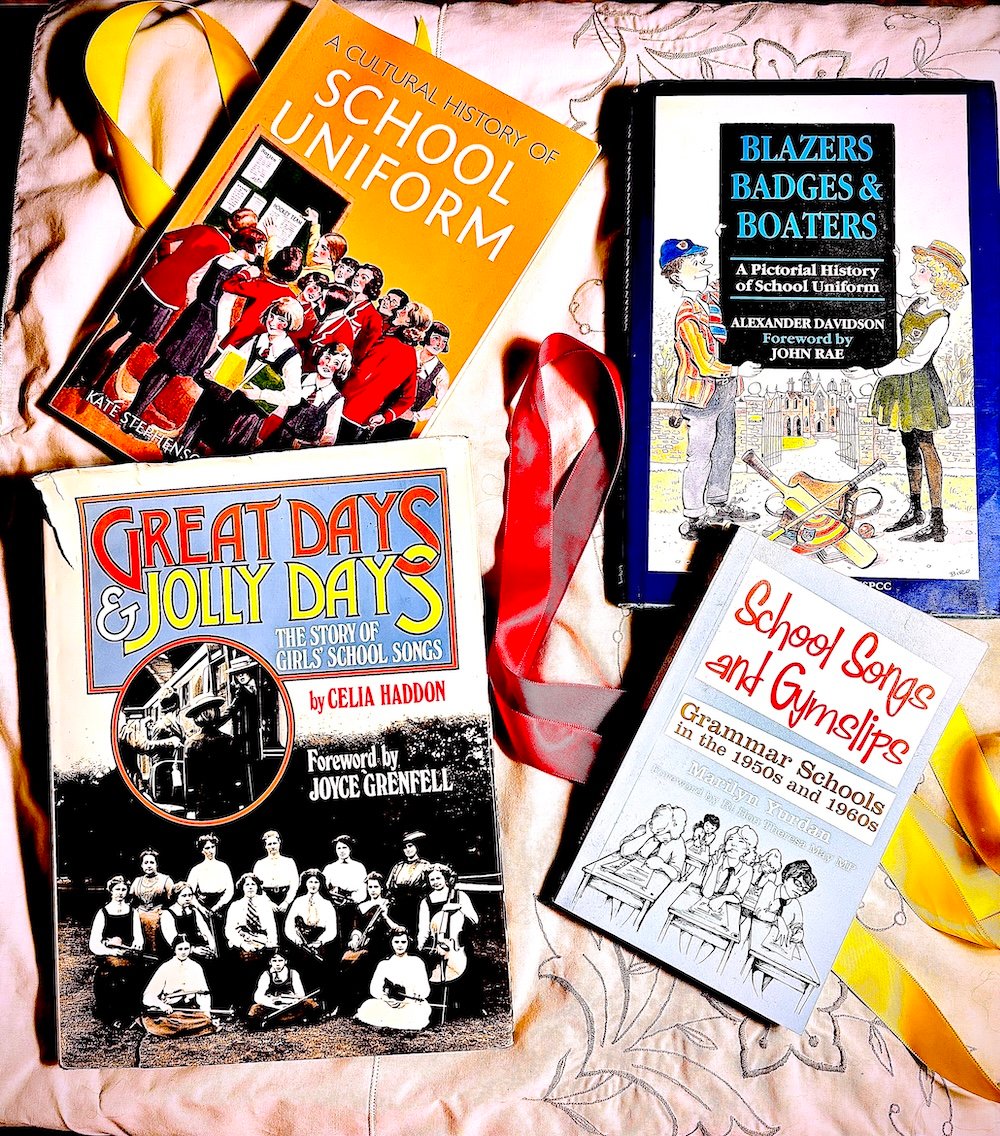

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by

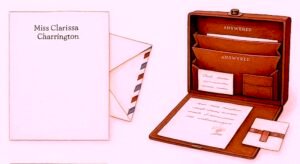

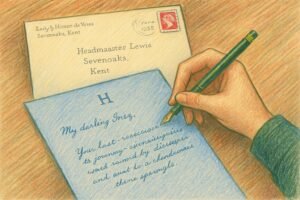

At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by  Trusting his indulgent understanding, Clarissa poured out her grievances to “Papa,” only to find he had abruptly transformed into “Father,” replying with all the ponderous dignity of the House of Commons. Clarissa, meanwhile, revealed a transformation of her own: the once devoted daughter emerged as a haughty, stroppy teenager, indignant at every turn and grandly refusing the hundred lines set for her. What might have remained a minor school punishment swelled into a correspondence campaign.

Trusting his indulgent understanding, Clarissa poured out her grievances to “Papa,” only to find he had abruptly transformed into “Father,” replying with all the ponderous dignity of the House of Commons. Clarissa, meanwhile, revealed a transformation of her own: the once devoted daughter emerged as a haughty, stroppy teenager, indignant at every turn and grandly refusing the hundred lines set for her. What might have remained a minor school punishment swelled into a correspondence campaign.

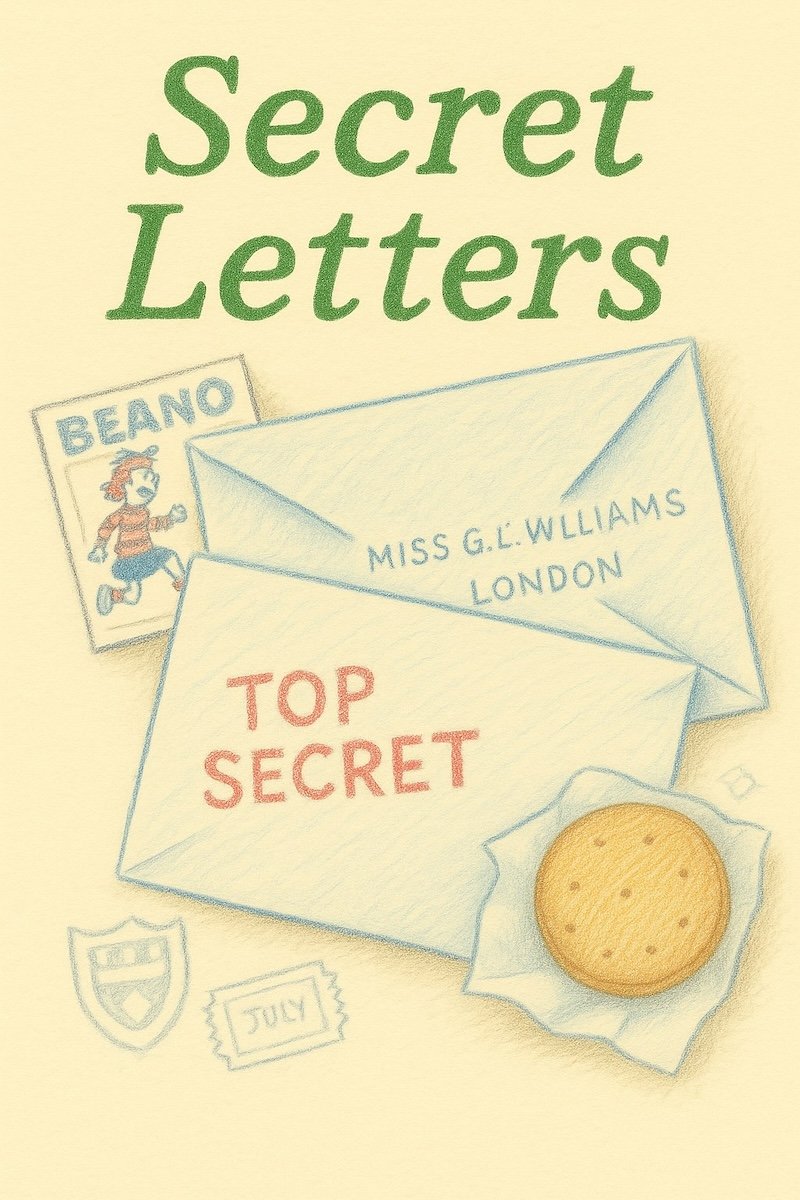

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.

Banner of “How to Read Inez of the Upper iV”The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

Banner of “How to Read Inez of the Upper iV”The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.