0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

Introduction

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages: tensions, alliances, secrets far too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here, and promise to respond. Moreover your ideas and reactions also join the archives, where they may quietly shape what comes next.

The MP Visits Saint Clare – Previously posted

The Archivist Gets the Last Word:

The Archivist Gets the Last Word:

When the last ink dried on Mr Fowler’s log: petrol topped, ham sandwiches eaten, punctual return to St Albans at four o’clock, the day and its record appeared, on their surface, neatly concluded. A tidy ledger of routes, meals, and mild discontent is precisely the sort of document one expects from a conscientious chauffeur in the summer of 1955. And yet any record, by its nature, resists such tidiness.

Friday, 8 July 1955

Friday, 8 July 1955

Foreword

Foreword

This tale follows

This tale follows  (This part of the text comes from the end of

(This part of the text comes from the end of  He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but.

He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but. The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by

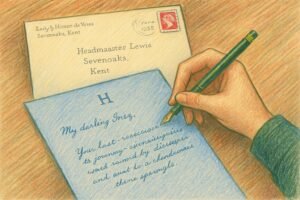

At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by  Trusting his indulgent understanding, Clarissa poured out her grievances to “Papa,” only to find he had abruptly transformed into “Father,” replying with all the ponderous dignity of the House of Commons. Clarissa, meanwhile, revealed a transformation of her own: the once devoted daughter emerged as a haughty, stroppy teenager, indignant at every turn and grandly refusing the hundred lines set for her. What might have remained a minor school punishment swelled into a correspondence campaign.

Trusting his indulgent understanding, Clarissa poured out her grievances to “Papa,” only to find he had abruptly transformed into “Father,” replying with all the ponderous dignity of the House of Commons. Clarissa, meanwhile, revealed a transformation of her own: the once devoted daughter emerged as a haughty, stroppy teenager, indignant at every turn and grandly refusing the hundred lines set for her. What might have remained a minor school punishment swelled into a correspondence campaign.

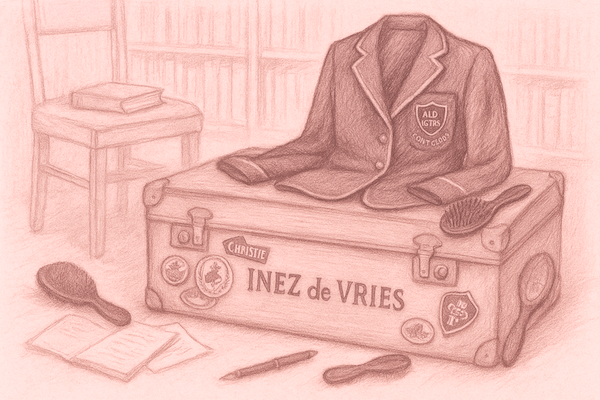

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.