6 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

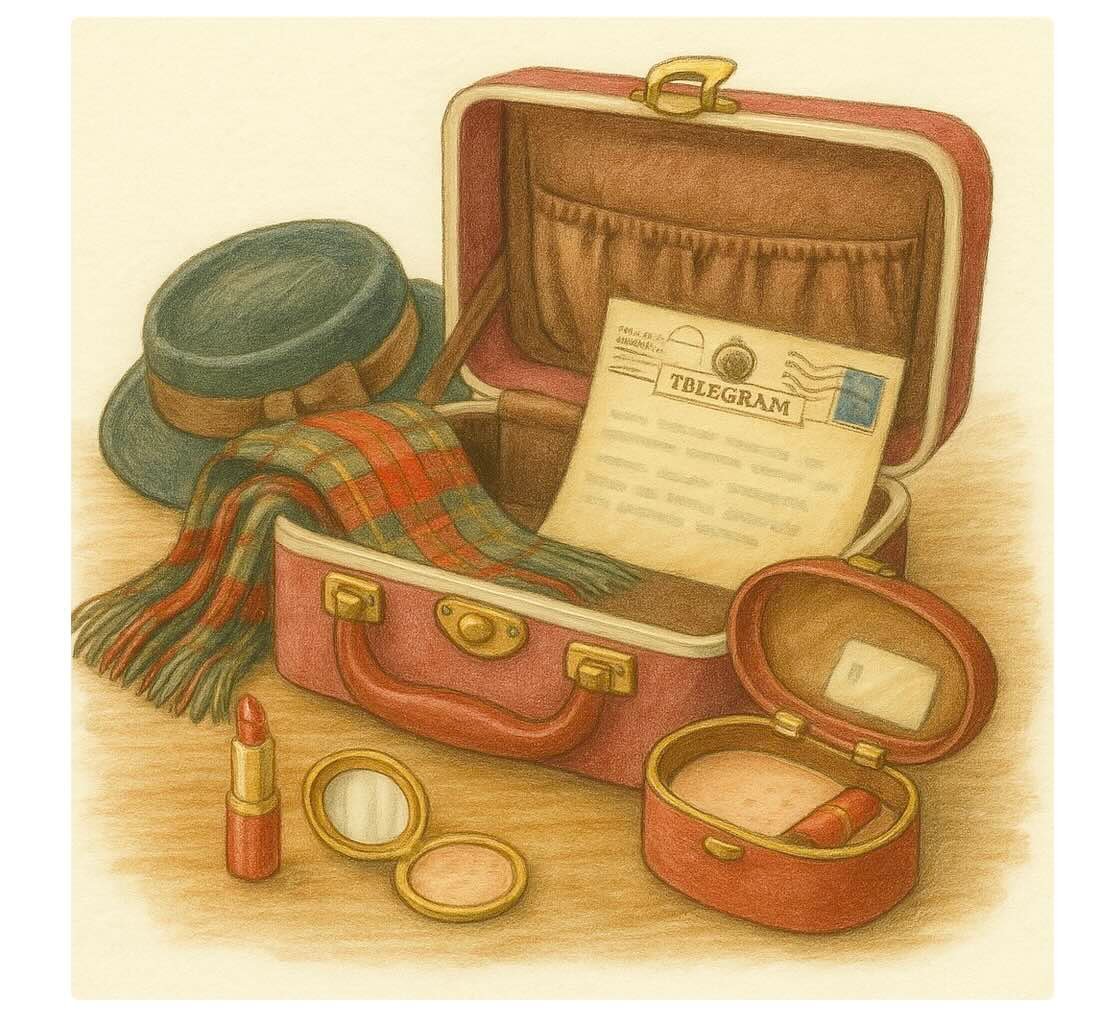

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a constellation of documents—some official, drawn from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others more intimate, taken from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font.

Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here, and promise to respond. Moreover your ideas and reactions also join the archives, where they may quietly shape what comes next.

Archivist’s Foreword

The following entry was written on the evening of 12 July 1955, after the party from Saint Clare had arrived at Bryn Derwen.

Unlike the previous document, which was composed under some pressure and at speed, this account was written in a place that ought to have been familiar and consoling, but was neither. It does not revisit the events of the Headmaster’s study (those are recorded elsewhere, and at some length), but concerns itself instead with what lingers once the official business is concluded, everyone has been properly seen to, and there is nothing left but supper, accommodation, and, possibly, tears at bedtime.

Former pupils may find the tone uncomfortably recognisable.

The MP Visits Saint Clare – Previously posted

Gladys’s Diary

12 July 1955

Evening (at Bryn Derwen)

The scene in the Head’s study was the worst of it. The rest of the day wasn’t as loud or dramatic, but it sat on me just as heavily. I cannot remember feeling so weary, so empty.

I never did drink the Head’s tea. Even the sandwiches looked poisonous, the bread curling at the edges, the ham shining faintly in the heat. I watched Gerald eat, cool as a cucumber. When the Head returned, he thanked him as if nothing more awkward than a recent school report had been discussed.

Foreword

Foreword

But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

But Inez is watching. And she remembers. This tale follows

This tale follows  – Sit where you are seen, not where you are heard.

– Sit where you are seen, not where you are heard.

Miss Gladys Williams

Miss Gladys Williams

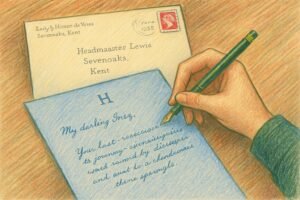

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

The

The

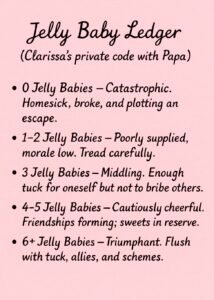

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.”

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.” Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply.

Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply. The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.

The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.