2 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

The brief tale that follows is not of Saint Clares’ in the 1950s, nor yet of the Upper IV. It comes from an earlier generation, set long before Inez first entered the school gates. In the unsettled autumn of 1938, Ned and Honour de Vries were newly wed. Told not through documents, but in the style of Regency romance, this story offers not a school record but a portrait of love, discipline, and loyalty in a world tilting toward war. Attentive readers may recognise here the same threads: secrecy, obedience, defiance, so important to Inez’s own story.

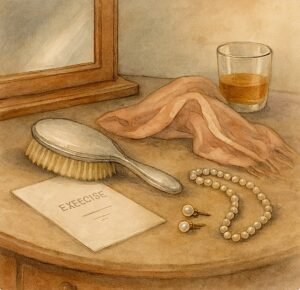

It was a London drawing room, heavy with smoke and restless laughter, late in the autumn of 1938. The newspapers still proclaimed peace, yet every sensible man felt the ground quiver beneath the headlines. Ned stood aloof, a whisky glass untouched in his hand, his eyes fixed on Honour, his young bride—radiant as a flame in pale silk, perilously bright.

The pale gown softened her beauty but betrayed her youth, making her seem more the debutante she had been months before than the worldly wife she fancied herself. Her laugh – pitched a shade too high, lingering a breath too long – drew the eager attention of every young man in the room. They mistook her inexperience for daring, her girlishness for sophistication.

When she mimicked the Prime Minister, tilting an imaginary umbrella and wobbling her voice in his plummy tones, the circle of young men roared with delight. She flushed with triumph, careless of the older women’s sharp glances and of the attaché in the corner whose eyes saw her not as a beauty but as a lever to be pulled.

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.

Once they left the party, he let his mask slip, stopped hiding his displeasure. They rode home in near silence, the hum of the motor car the only sound between them. Honour was still flushed with triumph, replaying her witticisms, humming, smiling as though she had carried the evening herself. To her, it had been another drawing room lark, a stage on which she sparkled. To Ned, it was a reminder that he was already driving headlong into a war declared in whispers, a phantom that would end only when the real one began.

At last she noticed his tension. “You’re cross with me,” she said, light as champagne bubbles. “Were you jealous, my husband? I did not think you insecure. It was but a bit of fun to pass the time.”

“You enjoy being noticed,” Ned replied flatly.

She smiled, careless. “Is that a crime, my Darlington?”

He did not turn his head. His gloved hands rested steady on his knees, his gaze fixed ahead.

“You enjoyed yourself,” he said finally, his voice level. “Too much.”

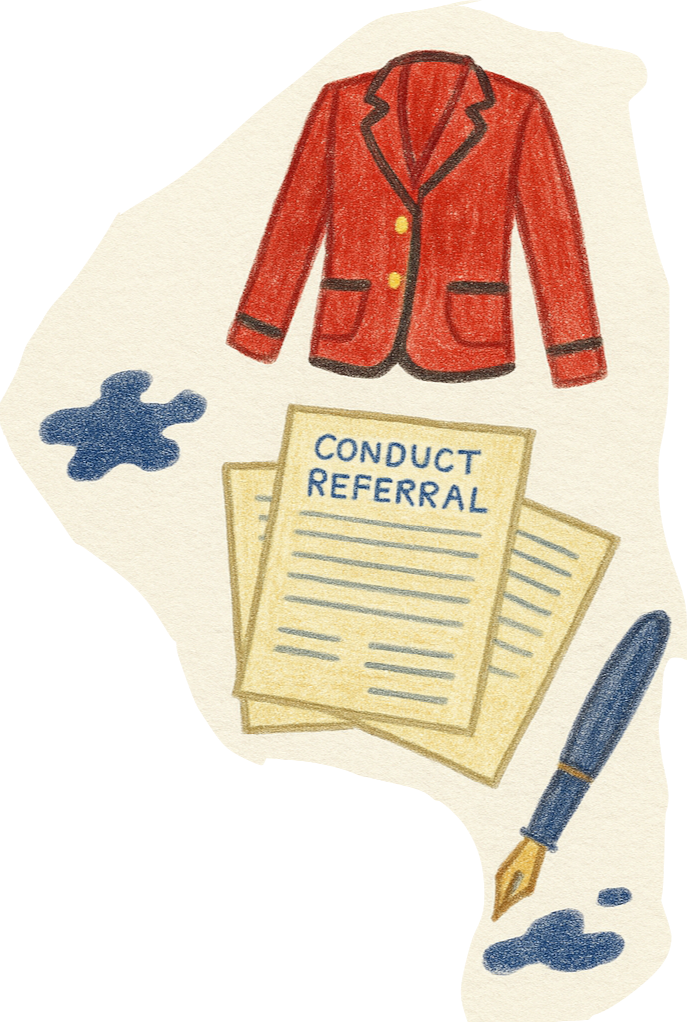

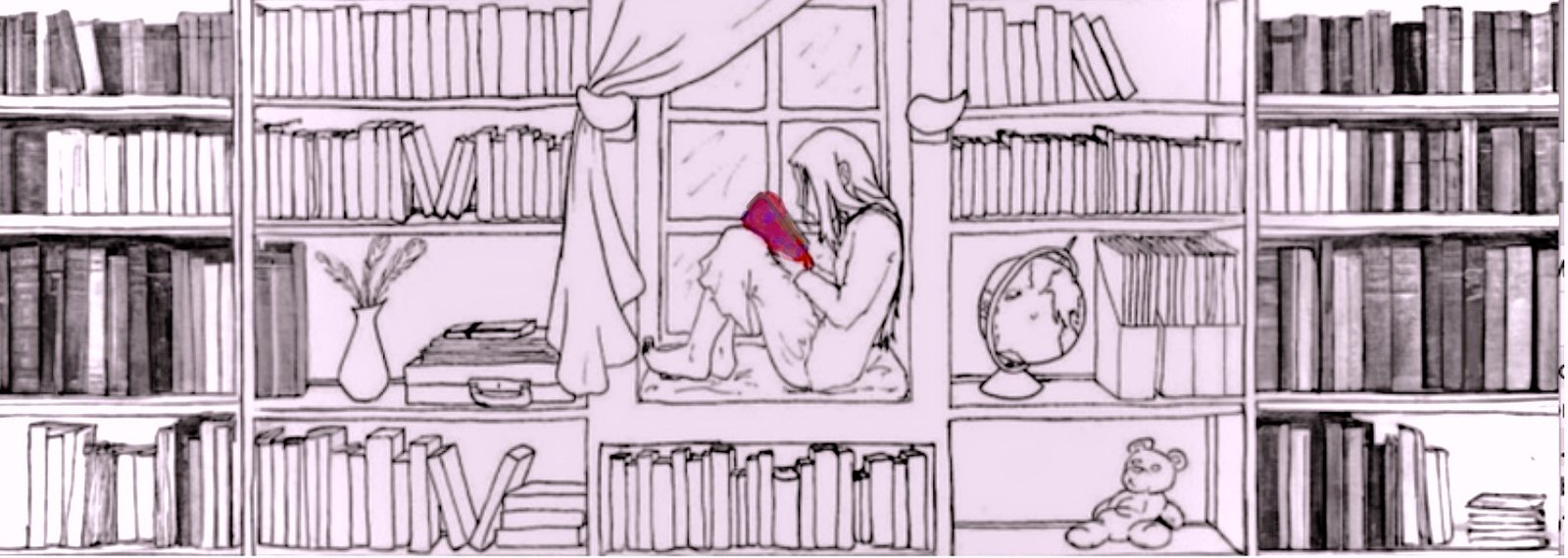

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

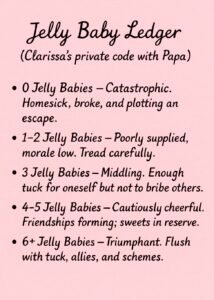

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.”

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.” Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply.

Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply. The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.

The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.