5 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

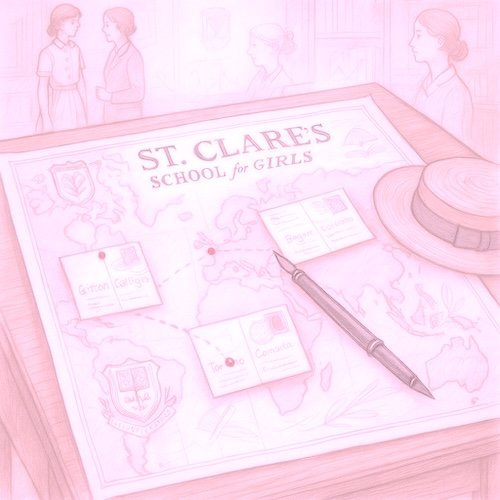

It has been brought to my attention — mostly via very kind readers, indulgent co-authors, one formidable academic, and more than once by a pedantic spouse — that the stories set in and around Saint Clare School for Girls do not follow a coherent educational model but shifts, sometimes jarringly, between UK and US education models.

To which I reply: yes. Quite.

Or: like, totally, dude.

Saint Clare School for Girls is a patchwork, a blazer-clad chimera. But in my defence, so is/was the history of girls’ education, especially in Britain — and I have the sources (and schoolgirl excuses) to prove it.

I started Saint Clare’s School for Girls as a one off, a whim so I could write “Tessa’s Summer Uniform,” a breathless little story, inspired by my 1999 wide-eyed visit to John Lewis in London (where I got a lovely boater) and a much-missed (and oft- discussed) uniform shop in Edinburgh: Aitkin and Niven.

I never intended it to be a series — I never ment to build a world. Mary Catherine’s world building work with Saint Francis didn’t exist yet, else I probably would have been intimidated into silence. Whatever my good qualities may be, consistency is not one of them.

Yet , paradox, I love tradition. Saint Clare isn’t one story, one time, nor does it exist in one place. Instead it borrows freely and globally from girls’ boarding school fiction and history.

Yes, Saint Clare’s traditions are occasionally contradictory. But then — so was reality. When Oxford and Cambridge were still squinting suspiciously at women applicants (Oxford grudgingly awarded degrees at a very few colleges in 1920; Cambridge waited until 1948 in any colleges, it was the late 1970s in others), clever girls with ambition often looked west. The Seven Sisters colleges in the U.S. — Wellesley, Smith, Bryn Mawr, and their ilk — had offered full degrees, rigorous coursework, and well-sharpened elbows since the 19th century.

There were lasting exchanges between British and American institutions surrounding women’s education going back to before the US Civil War. Some young women crossed the Atlantic for study and stayed in the US, changing and influencing elite US female education, making it more British. Others returned to Britain with transatlantic ideas and wearing sensible shoes. So if Saint Clare seems like it can’t quite decide whether it’s Malory Towers, Radcliffe College, or Harry Potter with Latin homework — it’s because it’s world is built on just such migrations.

Supporting Notes:

- Girton College, founded in 1869, was the first residential college for women at Cambridge. Women were not granted full degrees until 1948.

- Newnham College, founded in 1871, was a centre of women’s education and later a pipeline for wartime service (including codebreaking).

- Oxford began granting degrees to women in 1920, but Cambridge waited nearly three decades longer.

- The Seven Sisters colleges (Wellesley, Bryn Mawr, Smith, Vassar, Radcliffe, Barnard, Mount Holyoke) were America’s answer to the Ivy League for women — frequently hosted or corresponded with ambitious young British students.

- Girls from stricter British schools were sometimes dispatched to Toronto or Chicago when their Headmistresses deemed Cambridge ‘too soft.’ (This remains a highly enjoyable but currently untraceable anecdote.)

- More notes will be added, excuses provided, and sources invented as needed.

And if all that still doesn’t explain Saint Clare’s peculiar place in the digital and literary cosmos, I must remind you: the earliest stories were written not for print, but for the glorious chaos that was 1990s Usenet. It was there that Saint Clare first emerged, polished shoes and all, into the great adolescent commons of the early internet — a place oddly well-suited to school stories, which are, after all, about rules, rebellion, longing, and the vast emotional complexity of growing up in public.

And if EVEN all THAT isn’t enough to explain Saint Clare’s particular blend of precision and anachronism, I offer this personal note: I am myself the product of an all-girls school — not a boarding school, but the sort with hymns praising Mary in assembly, pleated knee-length skirts and a frightfully strict shoe policy. My mother attended, taught there, and served as an administrator. She, and the school’s other teachers, could spot a shirttail untucked or the wrong shade of socks at fifty paces.

My secondary school was also a beautiful place, designed with girls and young women in mind. The grounds were full of roses and vases of flowers filled the classrooms where advanced placement literature and calucus were taught. It’s hard to shake the rhythm of a schoolgirl’s day or being one of many in matching uniforms, at once unique and, well, uniform, once it’s in your bones.

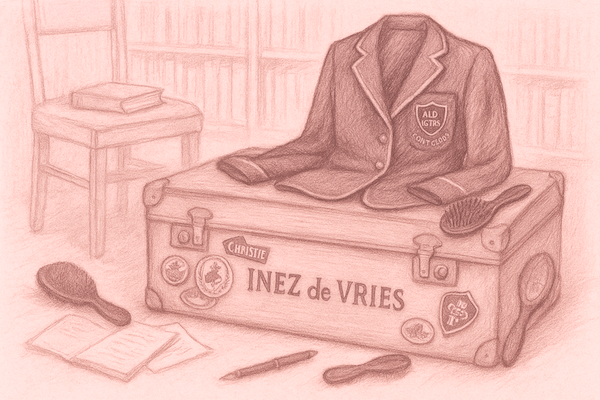

Beyond those, Saint Clare’s offers a particular blend of precision and anachronism In answer I offer this final exhibit: Aitken & Niven, a now-vanished department store on George Street in Edinburgh. When I spent the summers of 1999 and 2000 there, it was gloriously — stubbornly — out of time. The upper floor was entirely devoted to racks of school uniforms for every imaginable Scottish boarding school, alongside footlockers and racks of name-tag personalization forms. The floor was staffed by women who dressed like it was still 1959 and operated with the silent authority of minor royals. In the corner, there was a tea shop so British that when I left a one-pound tip, they chased me down the stairs to return it, assuming I had left it in error.

Tell me that’s not Saint Clare in miniature.