3 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here and promise to respond. Moreover your responses and ideas are included in the archives and may shift and change the story’s evolution.

Foreword

From the archivist:

The Charrington Papers, of which the present collection forms a small but telling part [see also Heard in the Charrington Household, Melodrama by Post, and The Secret Letters] offer a glimpse into the anxieties of an English household in the mid–twentieth century. The documents gathered here—letters, annotated responses, and private jottings—capture in miniature a struggle over authority and propriety between Gerald H. Charrington, Member of Parliament and self-appointed patriarch, and his sister-in-law, Miss Gladys Williams, a young woman who had the misfortune to combine a lively disposition with a poor instinct for discretion.

The Charrington Papers, of which the present collection forms a small but telling part [see also Heard in the Charrington Household, Melodrama by Post, and The Secret Letters] offer a glimpse into the anxieties of an English household in the mid–twentieth century. The documents gathered here—letters, annotated responses, and private jottings—capture in miniature a struggle over authority and propriety between Gerald H. Charrington, Member of Parliament and self-appointed patriarch, and his sister-in-law, Miss Gladys Williams, a young woman who had the misfortune to combine a lively disposition with a poor instinct for discretion.

Gerald’s concern, as his marginal notes repeatedly remind us, was not primarily with his own standing in the Commons (never more than modest) but with the long-term durability of the Charrington name. For him, a single ill-judged phrase, if repeated outside the family, could metastasise into a reputation for “wildness”—a quality, in his view, both unbecoming in a woman of five-and-twenty and indelible once attached. That his sister-in-law’s lapses might be mentioned in the Hertfordshire Gazette or (worse) among the parents at Saint Clare School was to Gerald a matter of great peril.

Gladys, for her part, complies outwardly—she had little choice—but her replies, clipped and formally correct, show a mastery of what might be called “obedience with barbs.” She acknowledges each of Gerald’s terms in turn, yet her diction—quotation marks, ironic phrasing, and finally the notorious sign-off, “Your ever-dutiful sister-in-law”—betrays a simmering contempt. Gerald, pen in hand, read her words as if they were a draft to be marked, underlining insolent turns of phrase and scribbling anxious comments about “damage” and “reputation” in the margins. His annotations, reproduced here, are at once the most revealing and the most inadvertently comic element of the collection.

The reader may choose to treat this exchange as a serious episode in the policing of female conduct in postwar Britain. Equally, one may detect in it the rhythms of a domestic farce: the ponderous elder brother pronouncing “terms” as if from the bench, the young woman skewering him with her pen even as she submits, and the lurking fear that the Gazette might carry word of it all. Either reading is legitimate; indeed, part of the value of the documents lies in their capacity to sustain both.

Letter from Gerald Charrington to Miss Gladys Williams

7 July 1955

My beloved sister Gladys,

Following our interview in the study this morning, I set down the following terms, which will remain in force until further notice:

-

-

- Your allowance is suspended. You will be provided with necessities at my discretion, but no sums for amusements, travel, or frivolities.

- You are not to remain in this house without either myself or Mrs. Fielding in residence. Neither are you to absent yourself on visits without my express approval.

- You will attend a course of domestic science at the St. Albans Institute. Mrs. Fielding will make the arrangements. Attendance is not optional.

- You will accompany me to Saint Clare School later this month, to answer directly for your actions in the matter of your niece and her friend.

- Fielding will remain in residence and will report daily by post. In addition, I will require a weekly written account of your progress from your teachers at the domestic science institute..

-

As to your question of when these restrictions will be lifted: that will be when I am confident in your maturity and judgment.

Gladys, I care for you as I have always done. It is because of that affection that I cannot allow you to go on as you have. Think of this less as a punishment than as a remedy, one that may yet set you on the sounder course you require.

I trust you understand me clearly. Please respond to this letter and indicate your understanding and agreement with each of the tenms.

Gerald H. Charrington

Gladys’ Letter to Friends in Scotland

9 July 1955

My dears,

Back in Hertfordshire and unable to rejoin you, though I had every hope of returning. You know how suddenly Gerald’s telegram came — and once he makes up his mind there is no appeal. So here I am, when I had thought to be out with you in the country for another week, riding across the moors and laughing over suppers after.

He has set me on a new “course of improvement” (his phrase), which means I am to be kept quite busy in St Albans for the rest of the summer. What a bore! Still, I shall make the best of it, and perhaps emerge more accomplished than before – though I would far rather be galloping beside you and enjoying the fresh air of Scotland.

Do write me every scrap of gossip. I am starved for fun and company, and need your letters more than ever.

Yours,

Gladys

Gerald,

In response to your letter, I acknowledge the terms you have imposed.

-

-

-

I understand that my allowance is suspended, and that I am to depend entirely upon your determination of what constitutes “necessities.”

-

I understand that I may not remain in this house unless you or Mrs. Fielding are present, and that I am not to make visits to others’ homes without being accompanied by you, or with your express permission – which you have indicated is improbable.

-

I understand that I am to attend the course of domestic science at the St. Albans Institute, my attendance being compulsory.

-

I understand that I am to accompany you to Saint Clare School, there to answer in person for my niece and her companion, as you require.

-

I understand that Mrs. Fielding will reside here, reporting daily by post, and that my instructors at the Institute will provide you with weekly accounts of my conduct and progress, for your satisfaction.

-

I understand that these restrictions will remain until you are persuaded of my “maturity and judgment.”

-

-

All points have been duly recorded.

Your ever-dutiful sister-in-law,

Gladys

Gladys’s Diary — 7 July, late night

Well. That was utterly BRUTAL. Gerald in his study – fire low, papers squared, voice flat as the House of Commons. As I walked in he stood and told me to sit, pointing to the chair in front of his desk. Told me I’d broken his trust. Told me I’d acted like a child laughed, tried to make light – said it was all theatre, a silly lark – but he cut me off. Two words: “Grow up.” Might as well have been a gavel.

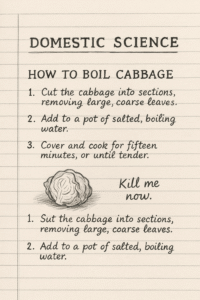

And then the letter. Formal, cold, spelled-out TERMS like a judge pronouncing sentence. No allowance. No visits. No house to myself. Mrs. Fielding set to spy on me – daily reports! And the crowning insult: domestic science at the Institute, with teenagers in hairnets boiling cabbage and polishing grates. ME, Gladys Williams, marched off to cooking class at five-and-twenty. It is intolerable.

I cried. Yes, I did. Couldn’t stop it. Not loud, but enough. He didn’t even hand me a handkerchief. Just let me sit there, red-eyed, while he watched, then shoved that letter across the blotter as if I were a schoolgirl signing my punishment lines. He told me he required a written response.

And now the guilt’s gnawing. Because Clarissa’s for it – I know she is. He swore it in his letter: “punished at school means punished at home.” Gerald never breaks his word. She’ll be bent over in that same study before the month is out, knickers down, and he’ll take up Margaret’s old prefect’s brush from the drawer. I know it too well.

Ten years ago, when I was 15, it was ME standing there. Twisting my hands, hearing him say, “You’ve shamed yourself and the family, and there’s only one remedy for that.” And then the brush – sharp and sharp again, until I sobbed and promised never. The sting of it, yes, but worse was knowing Margaret had once wielded it herself, and now Gerald keeps it as if it were sacred Scripture.

So here I am, 25, and still treated like I’m ten. Still caught out. Still scolded. Still crying. Still sentenced – to cabbage and sewing and Mrs. Fielding’s watchful eyes. And poor Rissie – she doesn’t even know what’s coming, but I do. And I helped set it in motion. Some aunt I am.

It’s beastly unfair. Unfair!! And I WON’T stand it meekly. I’ll find a way round him, I must – I will. Only… if I do, and it lands on Clarissa again, then what sort of aunt would that make me? What sort of girl? What sort of aunt? What sort of woman?

From the Charrington Papers

Letter: Miss Gladys Williams to Gerald H. Charrington, Esq.

9 July 1955

(With marginal annotations in the hand of Gerald H. Charrington, MP. Pencil and green ink on the original. Transcribed below with notes retained in brackets.)

Gerald,

[No courtesy, affection, or respect in the address. Terse.]

In response to your letter, I acknowledge the terms you have imposed.

[Correct form, though grudging.]

I understand that my allowance is suspended, and that I am to depend entirely upon your determination of what constitutes “necessities.”

[Quotations betray defiance. If repeated beyond these walls, could be read as derision – damaging if ever repeated outside the family.]

I understand that I may not remain in this house unless you or Mrs. Fielding are present, and that I am not to make visits to others’ homes without being accompanied by you, or with your express permission – which you have indicated is improbable.

[“Improbable” – insolent. Such words, if reported, would brand her as unruly. A young woman of her position must never appear so. Long-term consequences for the family’s but especially her personal standing if she is reported to be “wild.”]

I understand that I am to attend the course of domestic science at the St. Albans Institute, my attendance being compulsory.

[Acceptable wording. Yet she will chafe, and if she mocks the work publicly, it will be remembered.]

I understand that I am to accompany you to Saint Clare School, there to answer in person for my niece and her companion, as you require.

[Again grudging. A public scene must be avoided. Any hint of scandal around the girls will linger for years.]

I understand that Mrs. Fielding will reside here, reporting daily by post, and that my instructors at the Institute will provide you with weekly accounts of my conduct and progress, for your satisfaction.

[The phrase “for your satisfaction” is insolent. If spoken beyond our household, would appear she treats all guidance as tyranny. That perception, once fixed, will never leave her.]

I understand that these restrictions will remain until you are persuaded of my “maturity and judgment.”

[Quotations again – she scoffs at maturity. If she continues thus, she will be known as flighty, unreliable. That is a brand a woman never escapes.]

All points have been duly recorded and addressed.

[Flat, cold. No contrition.]

Your ever-dutiful sister-in-law,

Gladys

[Sarcasm plain. Behaviour grows more reckless. Not merely inconvenient – potentially ruinous in how others may speak of her. This cannot be allowed to take root.]

Poor Gladys. I cannot help but think this is not going to end well for her.

The word that comes to mind for her present attitude is “stroppy.” Not a complimentary view, but accurate, I think.

Interesting the similarities between her and Honour in that early stage of Honour’s marriage to Ned. A young woman of great natural gifts and powers, not yet aware of the consequences of wielding them with abandon. Gerald is being stern with her in order to guide her in that, but it seems not to be making a real, heartfelt impression yet. I wonder what might.

Stropy (which my autocorrect keeps changing to “stripy”) is *such* a good word for Gladys. And yes, her similarities to Gwen, minus Ned, are marked.

How, how to have her better live up to her potential?

Hey, you two. I do beg your pardon! I am in no way stroppy (nor, thankfully, stripy). This whole ridiculous situation is a tempest in my humourless brother-in-law teapot. No one else cares! It would be good if he could relax and be less of an MP and more of a man. Rather than suggesting I need a firm hand, maybe he needs appreciate what fine young women my niece and I are and stop trying to micromanage our mail.

He is not, I remind you both, MY father.