2 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here and promise to respond. Moreover your responses and ideas are included in the archives and may shift and change the story’s evolution.

Introduction:

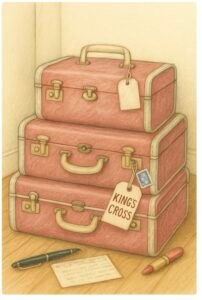

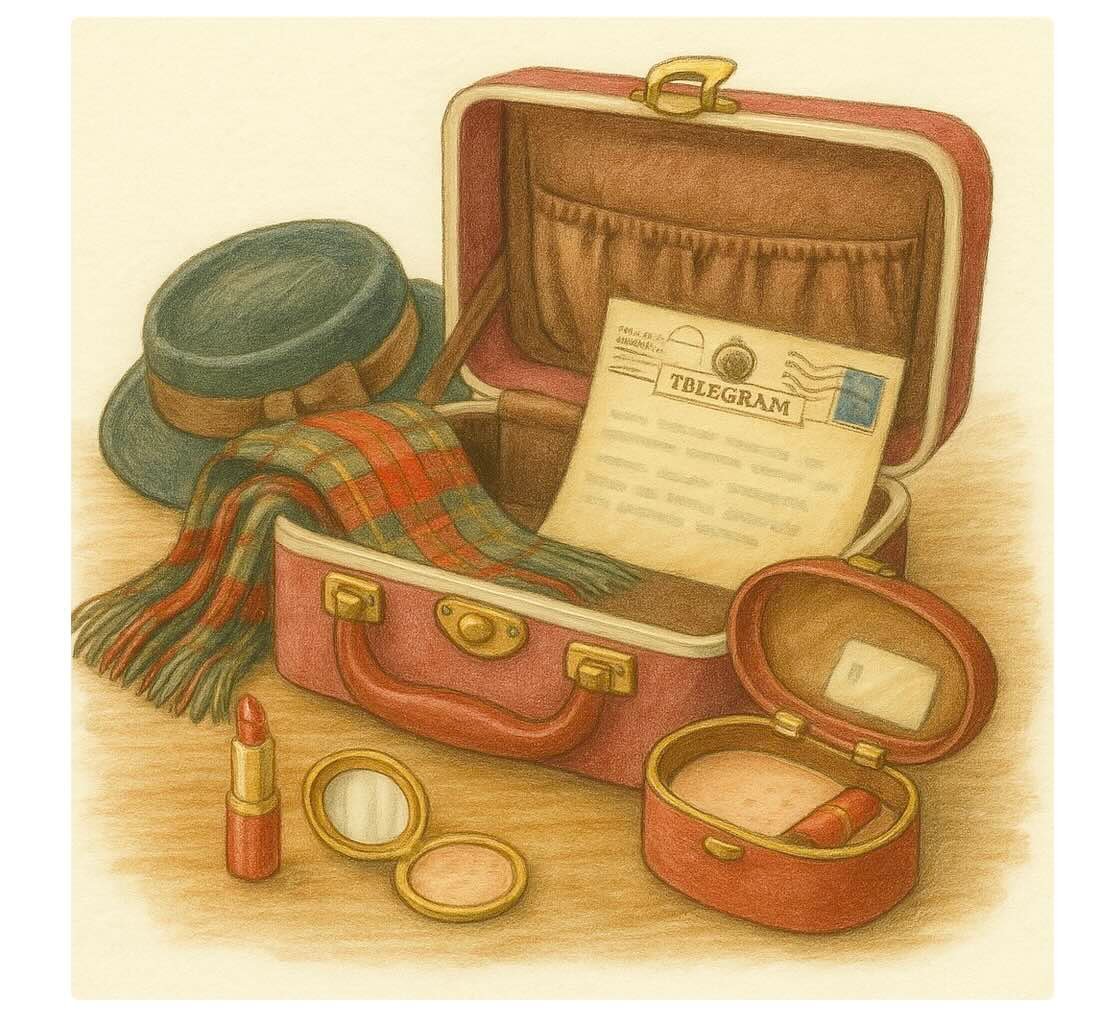

Miss Gladys Williams was enjoying herself in Scotland — scarves, suitors, and no shortage of attention — when a telegram from her brother-in-law yanked her home like a fish on a line. By the time she stepped off the train at King’s Cross, protesting she’d been “dragged back in chains,” the machinery of the household was already rattling back into place. The chauffeur collected her, the housekeeper was torn from her seaside holiday, and even a maid had to be fetched from the village. All this fuss over a single letter — one that should have stayed safely in the school office, but instead slipped out with Aunt Gladys’s obliging help.

Miss Gladys Williams was enjoying herself in Scotland — scarves, suitors, and no shortage of attention — when a telegram from her brother-in-law yanked her home like a fish on a line. By the time she stepped off the train at King’s Cross, protesting she’d been “dragged back in chains,” the machinery of the household was already rattling back into place. The chauffeur collected her, the housekeeper was torn from her seaside holiday, and even a maid had to be fetched from the village. All this fuss over a single letter — one that should have stayed safely in the school office, but instead slipped out with Aunt Gladys’s obliging help.

What happened once the front door shut was not meant for public ears. But houses have ears of their own. The chauffeur, the housekeeper, and the temporary maid each caught a part of the day’s drama, and their accounts, set side by side, give us the picture.

Here, then, is Heard in the Charrington Household, OR, The Day Miss Gladys Came Home.

Having trouble reading? Try the plain text version.

Private Notes of J. Fowler, Chauffeur

7 July 1955, King’s Cross Station

9:55 AM

Mr. Charrington and I arrived on the platform. Dark suit, bowler, gloves, umbrella. Car polished and ready, myself in uniform. His mood was grim.

Mr. Charrington and I arrived on the platform. Dark suit, bowler, gloves, umbrella. Car polished and ready, myself in uniform. His mood was grim.

I positioned a trolley where the first-class carriage was expected. Train in on time.

Miss Gladys Williams stepped down, breaking off with two young men who pressed their cards on her as though it was their right. Two porters trailed after with the luggage. She carried a small valise and a bright little handbag, face done up, headscarf tied like a cinema actress — not the thing for King’s Cross morning, but she’s always been a pretty girl and knows it. Too much indulged, if you ask me.

Exchange heard:

Miss Williams (too loud): Well, here I am, dragged back in chains!

Mr. Charrington (curt): Good morning, Gladys.

I said nothing but took the valise and set it on the trolley atop her other luggage. She clung to her little handbag as though I had offered to take it too. Her smile faltered then, as if she finally realized this was no game.

We walked off in silence. She tried chatter:

Miss Williams: It was only a bit of fun, Gerald — all blown up into a five-reel melodrama.

Mr. Charrington: We will not discuss it here.

While I saw to the cases, stowed them in the boot. Mr. Charrington opened the rear door himself, put her in, and then got in the other side.

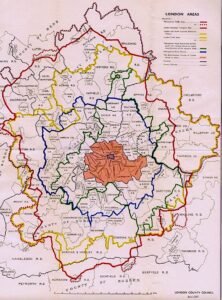

Drive: King’s Cross to the house outside St. Albans, about 1 hour.

For fifteen minutes she talked on — Inverness weather, a cinema in Aberdeen, some new American dance said to be all the rage. He gave no answers, made no inquiries. Instead he raised his news paper.

For fifteen minutes she talked on — Inverness weather, a cinema in Aberdeen, some new American dance said to be all the rage. He gave no answers, made no inquiries. Instead he raised his news paper.

At twenty minutes she tried again:

Miss Williams: I was only trying to help Clarissa, you know. I imagined you’d understand.

Mr. Charrington (flat): Your judgement and imagination failed you.

Half an hour on, silence, no discussion, only the traffic. She twisted the strap of her purse, glanced at him often. He held The Times on his knee, not reading, only lifting it each time she spoke, like a wall. I pitied her then, though it was plain she had asked for trouble.

At forty-five minutes she muttered:

Miss Williams: “Go on and play the heavy if you must.”

Mr. Charrington made no reply.

Arrival at St. Albans’: precisely 11:10.

He got out first, told me to carry the cases in. Motioned her to follow. She obeyed, her head down.

What passed between them beyond the hall door I cannot say. Only this: for all her bright talk and pretty ways, she looked that moment like a girl who’d finally come to the end of her rope.

Signed,

J. Fowler

Notes of Mrs. Dorcas Fielding, Housekeeper

7 July 1955, near noon

I had been only five days at Brighton, meaning to stay a fortnight, when the telegram came recalling me at once. Along with it came Mr. Charrington’s apologies — he knows well enough what an inconvenience it is to cut a holiday short, though I daresay he does not see all the practicalities. His house outside St. Albans was to be opened without delay, for he was returned from London and Miss Gladys with him. A poor end to a holiday, though I cannot complain — service is service.

I had been only five days at Brighton, meaning to stay a fortnight, when the telegram came recalling me at once. Along with it came Mr. Charrington’s apologies — he knows well enough what an inconvenience it is to cut a holiday short, though I daresay he does not see all the practicalities. His house outside St. Albans was to be opened without delay, for he was returned from London and Miss Gladys with him. A poor end to a holiday, though I cannot complain — service is service.

Though gone for less than a week, the house had been shut as if for a month. Dust sheets in every room, no fires laid, and not a loaf of bread in the pantry. I had seen to it myself before leaving, thinking there would be no one under this roof until August. To come back and undo it all for the sake of five days gone was a vexation, though not one I dared show. Only young Carter from the gardener’s cottage was about, and between us we pulled off what we could before the motor drew up.

Mr. Charrington came in first, hat in hand, face like stone. Behind him Miss Gladys, purse clutched, looking weary and more painted than I thought fit. She gave me a smile, but it would not stay. She has always been a beauty — one cannot deny her that — but a flighty young miss she remains, past the age when ribbons and excuses should serve. For my part, I never thought it wise of Mr. Charrington to leave her here so often, alone in the house with only the staff for company. Since young Miss Clarissa went off to school, he has been more at his London club than at home, and the result is plain enough.

At the foot of the stair he spoke, his voice sharp enough for me to hear plain:

Gladys, go upstairs and make yourself presentable. You will join me in the study directly.

She went up without a word, still holding that little purse.

He turned to me then, asking if I had been able to arrange any sort of luncheon at such short notice, and with no cook or maid to hand. I told him I had not called them back — they would not thank me for losing half their holiday, and I did not wish to risk them leaving for good.1Summer 1955 British unemployment was less than 1%., the lowest it has ever been. Even in the country there was a real fear of losing staff. But I had set young Carter to fetch a girl from the village, and between us we could put something cold on the table. Mr. Charrington nodded once, as if it would do, and went to the study.

Signed,

D. Fielding

Statement of Elsie Turner, temporary housemaid

Taken down by Mrs. Dorcas Fielding

7 July 1955

I was polishing in the study, not knowing Mr. Charrington was due home. When I heard his step in the passage I lost my nerve, thinking he’d be sharp with me for not finishing sooner. I slipped into the little smoking-room that opens off the study, meaning to wait till he was gone. I did not know the outer door was locked, so there was no way out but back through the study.

The door between is light wood, and I could hear near everything. Mr. Charrington’s voice was clear and hard, like men you hear on the wireless when they argue in Parliament. He told Miss Gladys she had broken his trust, told her she had acted like a child. She laughed at first, said it was nothing but theatre, a lark, but he would not have it.

Then he said two words:

Grow up.

Miss Gladys burst into tears.

It gave me a turn, hearing him speak to her so. She’s a lady of five-and-twenty, yet he spoke as if she were no better than a schoolgirl caught out. In my family, a woman that age would be married with children, running her own home. To hear her taken down like that, and then her crying so loudly after — it shook me more than I can say. He did not stir nor speak to comfort her. I crouched there trembling, not daring to move, until I heard her rise and go.

Mrs. Fielding found me at last, shut in and white with fright, and I told her how it was. I never meant to listen, but there was no other way.

Signed,

Elsie Turner

Annotation by Mrs. Dorcas Fielding

Poor child, she was near in tears herself when I found her, shut in that little room and white as milk. I don’t hold her to blame, it was bad luck she stumbled into it, but I told her plain what the rights of it are. If a word of what she heard goes round the village, I’ll know where it came from, and she’ll not find work again in this house nor any other decent one. She nodded quick enough, and I think the fright will keep her tongue still.

As for what she overheard, I can well believe it. Mr. Charrington’s manner when he sent for Miss Gladys told me what was coming, and I wasn’t surprised to hear the girl say she wept. She has been indulged too long, and it was bound to meet an end sooner or later. It is past time she was brought up sharp, though whether she will ever truly grow up remains to be seen.

I should not be surprised if Mr. Charrington means to take her with him to Saint Clare, to answer for herself before the Head. And perhaps that will do more for her than tears in the study ever could.

Signed,

D. Fielding

- 1Summer 1955 British unemployment was less than 1%., the lowest it has ever been. Even in the country there was a real fear of losing staff.

What tremendous fun.

If Downton Abbey has taught me anything–and it has taught me much–it is that there are no secrets in a house that employs anyone in service.

I think Gladys has much to be said in her favor: a bright young thing, blossoming after the burden of growing up through the war, clearly devoted to Clarissa. But having seen how her hauteur has made all of this so much worse for her, I cannot quite muster anything like sympathy.

I fear you may be right. She’s a good girl /young lady, really.