0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

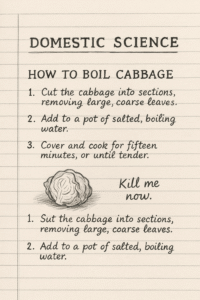

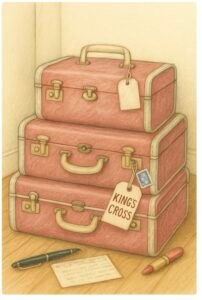

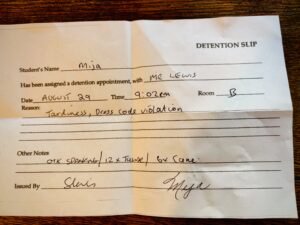

The story of Inez de Vries’s experiences in the summer of 1955 unfolds through a series of documents – some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages – the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained.

But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

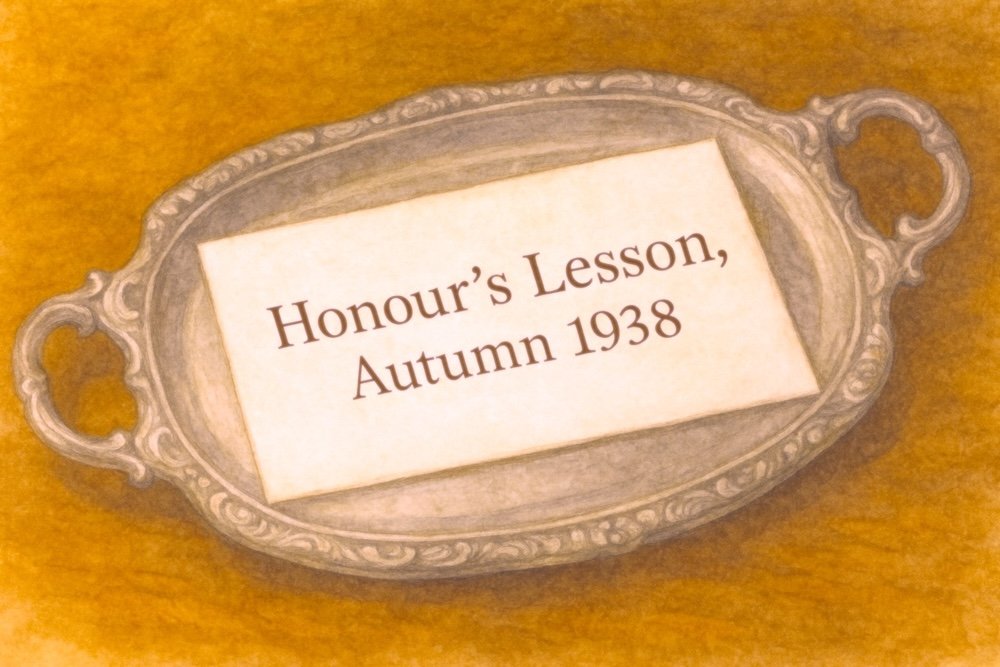

This story goes back to 1938 and tells the story of Inez’s parents, especially Lady Gwendolyn “Honour” deVries, a St. Clare Old Girl who notices far more than most people realize.

Note: Comments are read and much appreciated. Much as I like reading them on Twitter and Bluesky, I love getting them here and promise to respond. Moreover your responses and ideas are included in the archives and may shift and change the story’s evolution.

Having trouble with the handwriting? Try the plain text version.

Introduction

This tale follows Honour’s Lesson, where Lady Gwendolyn Randolph de Vries — Honour — first tested the patience of her new husband, Edmund Alexander de Vries, 9th Earl of Darlington. Like that earlier story, it begins in a more traditional narrative mode, borrowing the cadence of Regency romance. Yet here a new element enters: the reports of a bride still half a schoolgirl, too quick with her laughter, too eager for her husband’s notice, and learning how his sternness might be turned into intimacy. What she believes to be a private game of observation will, in time, shape far more than she imagines.

This tale follows Honour’s Lesson, where Lady Gwendolyn Randolph de Vries — Honour — first tested the patience of her new husband, Edmund Alexander de Vries, 9th Earl of Darlington. Like that earlier story, it begins in a more traditional narrative mode, borrowing the cadence of Regency romance. Yet here a new element enters: the reports of a bride still half a schoolgirl, too quick with her laughter, too eager for her husband’s notice, and learning how his sternness might be turned into intimacy. What she believes to be a private game of observation will, in time, shape far more than she imagines.

Though not set at Saint Clare’s, its themes are familiar: discipline, secrecy, defiance — threads that are woven through the school itself.

From The Archivist:

From the Lady de Vries Collection, Blue Room Archives, Saint Clare’s School for Girls)

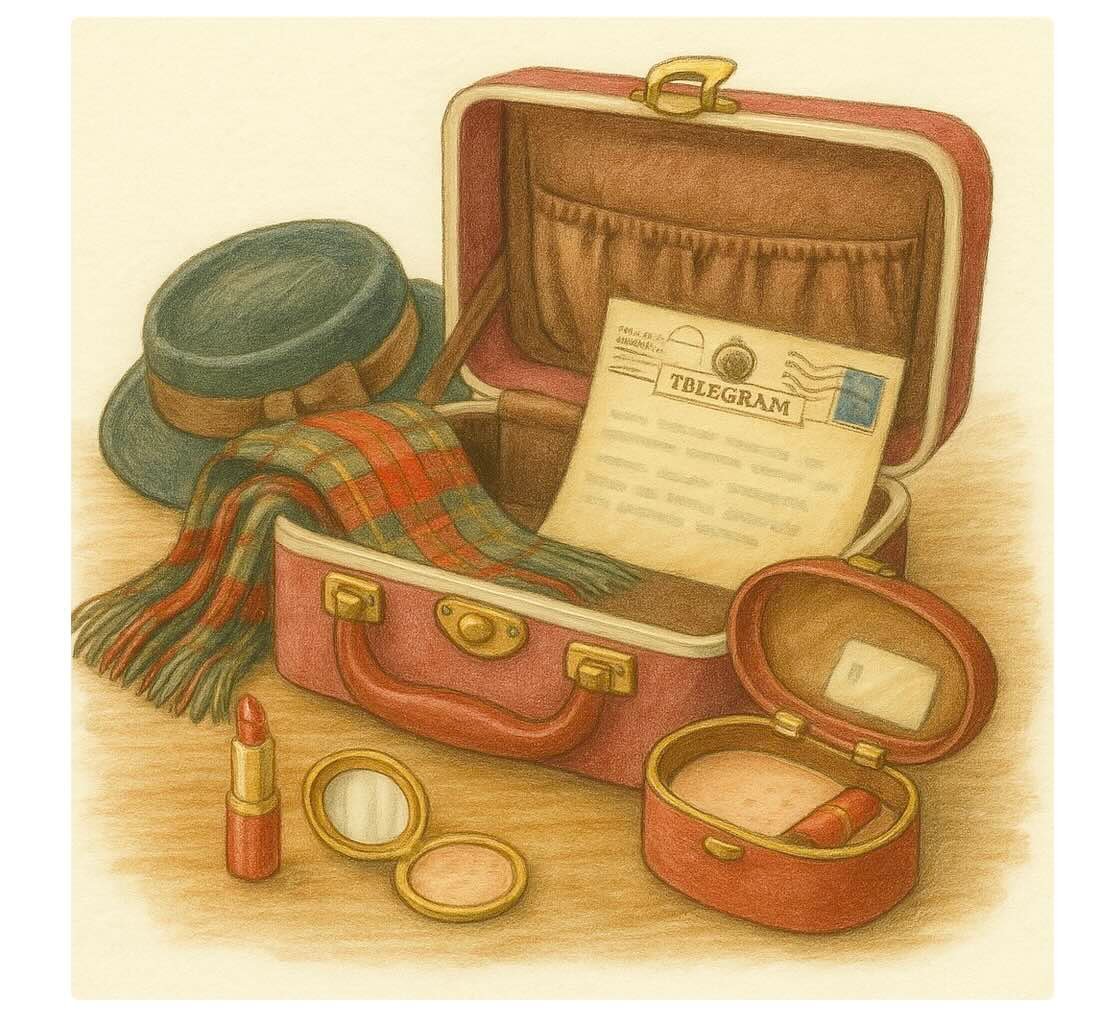

The papers presented here form part of what is now known as the Lady de Vries Collection. Though the correspondence was originally preserved among the private files of her husband, Edmund Alexander de Vries, 9th Earl of Darlington, its preservation and eventual deposit at Saint Clare’s are due to Lady Gwendolyn Randolph de Vries herself.

The exchange of initials — D. and H. — occurs throughout. Their precise origins are unclear; however, internal evidence suggests that these letters were both a private correspondence between husband and wife and, increasingly, a record of informal “exercises” undertaken by Lady de Vries during the late 1930s.

The editors have retained the original orthography and punctuation. A few later pencil notes in Lord Darlington’s hand are reproduced in grey type. Where the line between affection and assignment blurs, readers are invited to remember that the world beyond these pages was also shifting — toward war, secrecy, and a very different kind of education.

Part One

If you haven’t read the Prologue yet, you should.

Note from D. –

11 November 1938

Honour,

You are attending Lady Fenton’s gathering tomorrow. Treat it as exercise.

– Sit where you are seen, not where you are heard.

– Sit where you are seen, not where you are heard.

– One glass of champagne, no more.

– Listen more than you speak. Note what is certain, and what you only suppose.

– Write it after, neatly, as if for school.

Report due upon return, as soon as possible. Marks for observation, not embroidery. Late submissions will not be entertained, .

D.

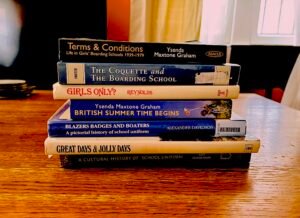

Even with getting to hand out with Rex and Adalia, my biggest September news is <cue trumpets>: after being abruptly shuttered five years ago,

Even with getting to hand out with Rex and Adalia, my biggest September news is <cue trumpets>: after being abruptly shuttered five years ago,

—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. (This part of the text comes from the end of

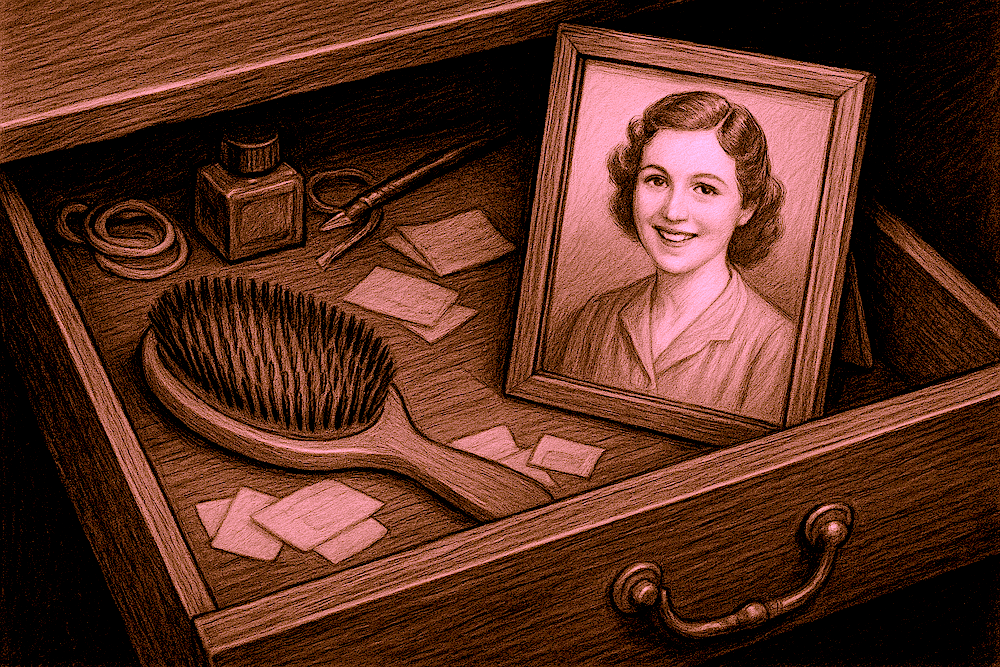

(This part of the text comes from the end of  He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but.

He sat at his desk while sh slept. He could not silence her — Honour was not a woman who could be silenced, or remain chastened for long without planning rebellion. She was too beautiful not to be noticed, even had she been inclined to play the wallflower — and her debut season had already proved she was anything but.

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.

Ned’s jaw tightened. To the others, she was a charming bride showing off her sparkle. To him, she was a bright flame catching against dry kindling. He saw the peril of innocence mistaken for invitation, the danger of brilliance wielded without care. He sensed gossip already clinging to her like sickly perfume, a risk that could be stored, repeated, used. He admired her wit – how could he not? – yet threaded through the gaiety he heard something else: the false brightness of a society pretending it was not on the verge of war.

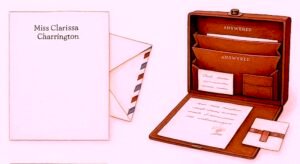

The Charrington Papers, of which the present collection forms a small but telling part [see also

The Charrington Papers, of which the present collection forms a small but telling part [see also

Miss Gladys Williams

Miss Gladys Williams

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by

At Saint Clare’s, it is a truth universally acknowledged (at least by

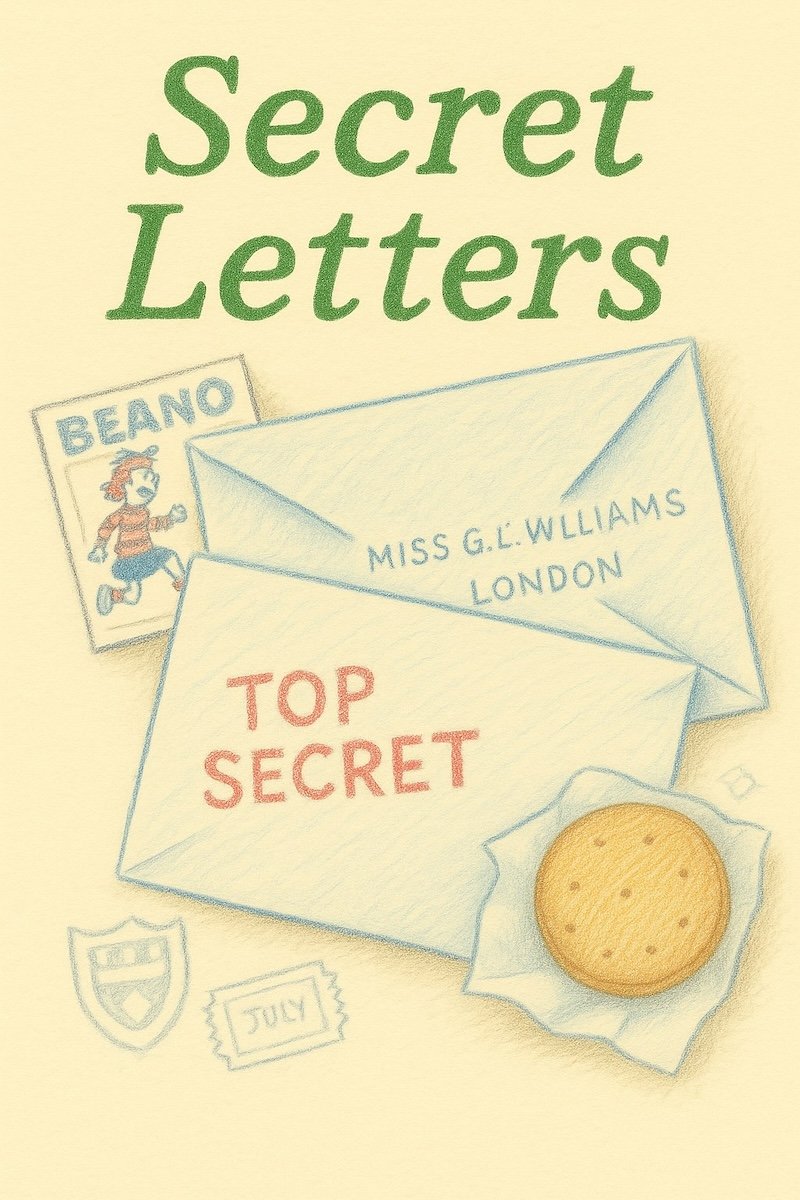

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.

The Secret Letters exchange began when Clarissa Charrington slipped a note into the post for her aunt Gladys, with Beano clippings and a sly message from Inez de Vries tucked inside. Gladys, amused and willing, forwarded the enclosure under her own respectable cover. In this way, the girls’ words travelled by official post — yet hidden in plain sight, a letter within a letter.