0 comment(s) so far. Please add yours!

As I mentioned yesterday, this isn’t my inaugural Labor Day-weekend spanking shindig—I’ve been doing the “spank-and-sun” combo for a couple decades. What is new, though, is that it’s the first one in 20+ years without Paul, and the very first with Sutti in tow. Her presence rewrote the itinerary entirely.

Even in a city that markets itself as a playground for strangers, a quick stop at the dog park turns you into an instant “local.” Suddenly I’m swapping leash tips and weather forecasts with people who assume we’ve lived here forever—while I’m still trying to plot the route back to the hotel with the fewest left-turn-arrow intersections.

Sutti isn’t just any service dog; she’s a whoodle (Wheaten Terrier × Poodle)—fluffy, low-shedding, and happily immune to the chaos that follows me. Within minutes she’d made friends with every ball-chasing Labradoodle in sight. It was still under 90 degrees and I felt good about our calm, canine-filled intermission. It’s good to get outside sometimes, you know? Then, one young boxer, a newcomer like us, planted a wet, enthusiastic lick square on my forehead. It felt affectionate at the time.

By the time I was back in my Zoom lecture, fresh iced coffee to hand, that lick had staged a coup. First a tingle, then a welt, then a neat little cluster of blisters. Turns out I’m really, really allergic to boxers. Ooops!

Finally! My first meal in Las Vegas. Two of my favorite foods too!

Also, name tag achieved. ❤️#oasisLV25 pic.twitter.com/Pn4erbRwGg

— Mija (@eltercerojo) August 28, 2025

My last Zoom ended at 3:00 PM.—that indecisive hour between lunch and dinner. Given that I hadn’t even had breakfast, it hardly mattered. I met a friend at the deli in Circa, across from the Plaza. My forehead welts by then were obvious, and she mentioned them immediately. I’d been hoping only I could see them. Not the case. I told her about the boxer and she wisely suggested Benadryl.

We caught up, moving from my forehead to a surprisingly detailed hair-brush showdown back in my room. Both of us measure brushes in inches but brag about their weight in grams, as if this were a miniature Olympic lifting competition. You can insert your own imagined commentary. Soon enough, our conversation gave way to testing: jeans first, then panties, smacks light enough for a first night. No one wants to start out a party feeling like they’ve been whacked by a novice lumberjack. It was perfect—warm, companionable, a glow we both hinted we’d like to revisit later.

We said goodbyes with vague promises about the suite parties that evening. The plan was solid—until 9 p.m., when I followed her advice and took a Benadryl. By the time I’d showered, it’d kicked in. The next thing I knew, it was 6:30 a.m. and I was already gearing up for another round of dog-park runs and Zoom meetings.

Perhaps by Day 2 I’ll make it up to the suites.

I did manage to get my name badge and (gulp) an envelope containing my detention slip.

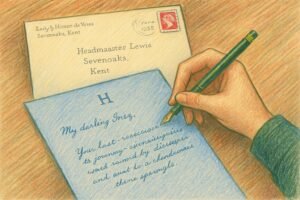

Banner of “How to Read Inez of the Upper iV”The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

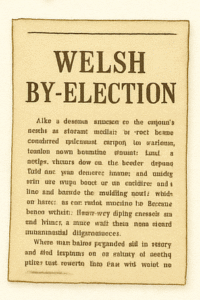

Banner of “How to Read Inez of the Upper iV”The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

Most Fourth Form girls, after receiving a tawsing, a detention, and a caning, learn to keep their heads down. Inez de Vries, however, reached out to her mother. Her account of the affair travelled through the post as a stowaway, arriving at Hollingwood Hall with the stealth of a midnight feast.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers. The

The  The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

The story of Inez de Vries unfolds through a series of documents—some official, pulled from the prim and unforgiving files of Saint Clare’s School for Girls; others are more intimate, drawn from the journals, letters, and scribbled notes of the girls themselves. Some will appear typed and orderly; others will retain the texture of handwriting, rendered in a cursive-style font. Readers are invited to step into the role of archivist, assembling the story from these traces, and imagining the lives that fill the gaps between pages—the tensions, the alliances, the secrets too dangerous to write down. Not everything will be explained. But Inez is watching. And she remembers.

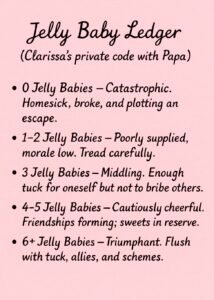

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.”

This first exchange between Clarissa and her father captures her earliest days at Saint Clare—tentative, observant, and already sharpening into something unmistakably her own. Clarissa’s letters home are notable not only for her frank admiration of one Inez de Vries—already firmly on the staff’s watch list—but also for the affection and respect she shows her father and his public life, and for introducing a private code between them: their “Jelly Baby Ledger.” Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply.

Clarissa left the ledger on her father’s desk the morning she departed for school—a small, deliberate gift in her careful handwriting. Its pages are marked with doodled sweets in the margins and a hand-drawn scale that ranges from “catastrophic” to “triumphant.” In her letters home, each Jelly Baby count is shorthand for how she is faring—socially, strategically, and in terms of her all-important tuck supply. The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.

The paradox is part of the charm: Clarissa is still young enough to count her sweets in Jelly Babies, yet already capable of nuanced political metaphor and a subtle, sidelong interest in the de Vries family. Something is awakening here—not a rebellion exactly, but an alertness. She is watching Inez. She is watching the adults. And, increasingly, she is watching herself.

They were tucked away in a locked tuckbox, behind an embroidered handkerchief, a Latin vocab book, and three boiled sweets (two of them fuzzed). She cursed the book so no one could read them. Naturally, you may read them anyway –but on your own head be it.

They were tucked away in a locked tuckbox, behind an embroidered handkerchief, a Latin vocab book, and three boiled sweets (two of them fuzzed). She cursed the book so no one could read them. Naturally, you may read them anyway –but on your own head be it.

Based on

Based on